The Proverbs of Hell 15/39: Sakizuke

SAKIZUKE: Variantly spelled “sakizuki” and “saki-zuke,” the latter on Janice Poon’s blog, where she describes it as “a sampling of small appetizers whose ingredients, garnishes, and dishware sets the tone for the season and invites the gods to partake of the meal.” Wikipedia, meanwhile, directly compares it to an amuse-bouche, I.e. the second episode of the first season.

SAKIZUKE: Variantly spelled “sakizuki” and “saki-zuke,” the latter on Janice Poon’s blog, where she describes it as “a sampling of small appetizers whose ingredients, garnishes, and dishware sets the tone for the season and invites the gods to partake of the meal.” Wikipedia, meanwhile, directly compares it to an amuse-bouche, I.e. the second episode of the first season.

The killer-of-the-two-weeks here is given an unusual sort of focus. On the one hand he’s the least sketched out killer the show has ever done – he’s literally only in the script as “Muralist,” and essentially everything we learn about him is projected onto him by other characters. On the other, Roland Umber’s awakening inside the mural is used as the cliffhanger, and the second episode luxuriates in this cold open, giving the sheer and visceral horror of the mural room to breathe. Fuller has said that his inspiration for this killer was equal parts Busby Berkeley and the film Jeepers Creepers, which is a pair of inspirations that boil down to “this is why you are the perfect showrunner for Hannibal.”

The wide shot of Roland, already making a probably fatal leap into the water, being dashed upon the rocks is a surprisingly black comic beat to end on after a very straight horror movie chase through a cornfield.

In an understandable move to avoid having all of Will’s scenes for the first six episodes take place in the same set, Fuller and company have crafted a second asylum location based on bright, stark whiteness instead of gloomy darkness, with the discrete white cages doing the work of making the space disturbing. It’s a triumph of design, managing to be a more impressive location than the iconic subterranean cell.

WILL GRAHAM: I’ve lost the plot. I’m the unreliable narrator of my own story. I’m trying to place myself somewhere in the frame of my mind and I have no bearings. No landmarks to tell me who I am.

ALANA BLOOM: You have an incomplete self. We are who we are in the now and we are the sum of our memories. There are pieces of you… you can’t see.

Will opens with a pair of lines that are starkly meta even for Hannibal. (Though who among us is anything other than the unreliable narrator of our own story?) The exchange is on the whole familiar – it’s restating stuff we’ve been dealing with explicitly (Hannibal doesn’t really deal with things in any other way) since “Rôti.” Of course, there’s a reason for this.

WILL GRAHAM: I’m… very confused.

ALANA BLOOM: Of course you are. Ideas and perceived experiences have the same effect on our minds as tossing a rock into a pond. It all ripples.

HANNIBAL: Let us help you, Will. Let me help you.

WILL GRAHAM: I need your help.

This exchange is followed by a scene of Will, still shaking with the emotion of this scene, being led back to his cell, where, once alone, the mask of overwrought emotion drops and it becomes clear that he was manipulating Alana and Hannibal through this entire exchange. Doing this to Hannibal makes sense and, indeed, is self-evidently savvy. Doing it to Alana, on the other hand, is easily the most callously cruel thing Will has done to date.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I reached the limit of my efficacy. I don’t believe I can help you.

HANNIBAL: Are you giving me a referral?

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I’m not. I’m just ending our patient-psychiatrist relationship.

HANNIBAL: You tried to end it before.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I’m grateful for your persistence with engaging me after my attack. However, in light of all that’s happened with Will Graham, I’ve begun to question your actions. Particularly, your past actions with regards to me. And my attack.

HANNIBAL: Did you share these questions with Jack Crawford?

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: No. Nor am I going to. I would look just as guilty as you. And perhaps that’s what you intended.

HANNIBAL: What exactly am I guilty of?

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: Exactly, I can’t say. I had to draw a conclusion from what I glimpse through the stitching of the person suit you wear. And the conclusion I’ve drawn is… you are dangerous.

Though in part born of the basic necessity of working around Gillian Anderson’s exquisitely busy schedule (she was also appearing in The Fall and Crisis and found time to notch two film roles in 2014 to boot), this sequence of her retreating from interaction with Hannibal is all the same magnificent. This is the first time we’ve seen someone looking at Hannibal from the outside work out what he is, or, more interestingly, part of what he is – the part that peaks out through his person suit. (Note also how that metaphor, once it acquires “stitching,” becomes much more visceral, more directly invoking Buffalo Bill.)

HANNIBAL: The color of our skin is so often politicized, it would almost be refreshing to see someone revel in the aesthetic for aesthetic’s sake. If it weren’t so horrific. We’re supposed to see color, Jack. That may be all this killer has ever seen in his fellow man. Which is why it’s so easy for him to do what he does to his victims.

There are many differences in approach between Hannibal and Will in how they assist the FBI, but the funniest by some margin is Hannibal’s inability to resist critiquing the murderers. Here his appreciation for the unnamed muralist is clear and, more interestingly, rooted in a remarkably sympathetic musing on the separation of skin color (and recognition of skin color) from the political realities of racism. We’ll ignore the fact that this aspect of the muralist’s work is basically dropped after this scene.

BEVERLY KATZ: You think he’s innocent.

JACK CRAWFORD: I don’t know what I think.

BEVERLY KATZ: I think he still wants to save lives. That’s what I think.

JACK CRAWFORD: I’ve bent rules here in the name of trying to save lives. But there is an internal investigation. I am under a microscope. The Office of the Inspector General has ordered a psych evaluation to determine my competency to sit in that chair.

BEVERLY KATZ: I’m sorry, Jack. What do you want me to do? If you don’t want me to go back, I won’t.

JACK CRAWFORD: We didn’t have this conversation. And since we didn’t have this conversation, you should do what you believe it is your job to do.

Vintage Jack Crawford, demonstrating his M.O of running a vast number of quasi-authorized agents who take what might be called “nontraditional approaches” to investigation. Also his M.O. of this resulting in horrible things happening to them, but we’ll get there in a few episodes. For now, what’s interesting is Beverly’s accurate assessment of Will’s motivations. In his weekly series of interviews with the AV Club about Season Two, Fuller repeatedly highlights the scene in “Kaisecki” where Beverly shows Will the photos as a favorite bit of the season due to Dancy’s performance of Will’s disappointment when he realizes Beverly isn’t there out of friendship. But she is still, more even than Alana, inclined to believe in Will’s innate goodness.

HANNIBAL: I’ve been advised to stay on this side of the white line.

WILL GRAHAM: Select patients have taken to urinating on the therapists.

HANNIBAL: I would argue, drawing a line might encourage a pissing contest.

WILL GRAHAM: I’m not interested in a pissing contest with you, Dr. Lecter.

I feel an obligation to highlight these lines in terms of trolling Will/Hannibal shippers, but I honestly don’t know where to go from setting up that joke.

WILL GRAHAM: I’m wondering if you can get me the thing I really want.

BEVERLY KATZ: Try me.

WILL GRAHAM: I want you to ignore all the evidence against me.

BEVERLY KATZ: You’re right. I can’t get that.

WILL GRAHAM: How many more colors is this killer going to add to his box of crayons?

BEVERLY KATZ: Say I were to ignore the evidence against you, what then?

WILL GRAHAM: Strike it from your mental record. Start over. If I’m guilty, you’ll find more evidence. If I’m not guilty, maybe you’ll find that too.

BEVERLY KATZ: All right. I’ll keep looking.

As one would expect from Will, this is a framing perfectly tailored to Beverly’s psychology: pragmatic, rational, and rooted in her consistent desire to be Will’s friend.

Beverly declines to give Will privacy for this reconstruction, and so he turns his back to her and begins looking at the photos. This results in a cut to the imagined morgue with the interesting detail of Beverly being pulled into Will’s imaginary space. I would point out that within the narrative framework of Hannibal, there is literally no reason to suspect that Beverly is not aware of her presence in this space.

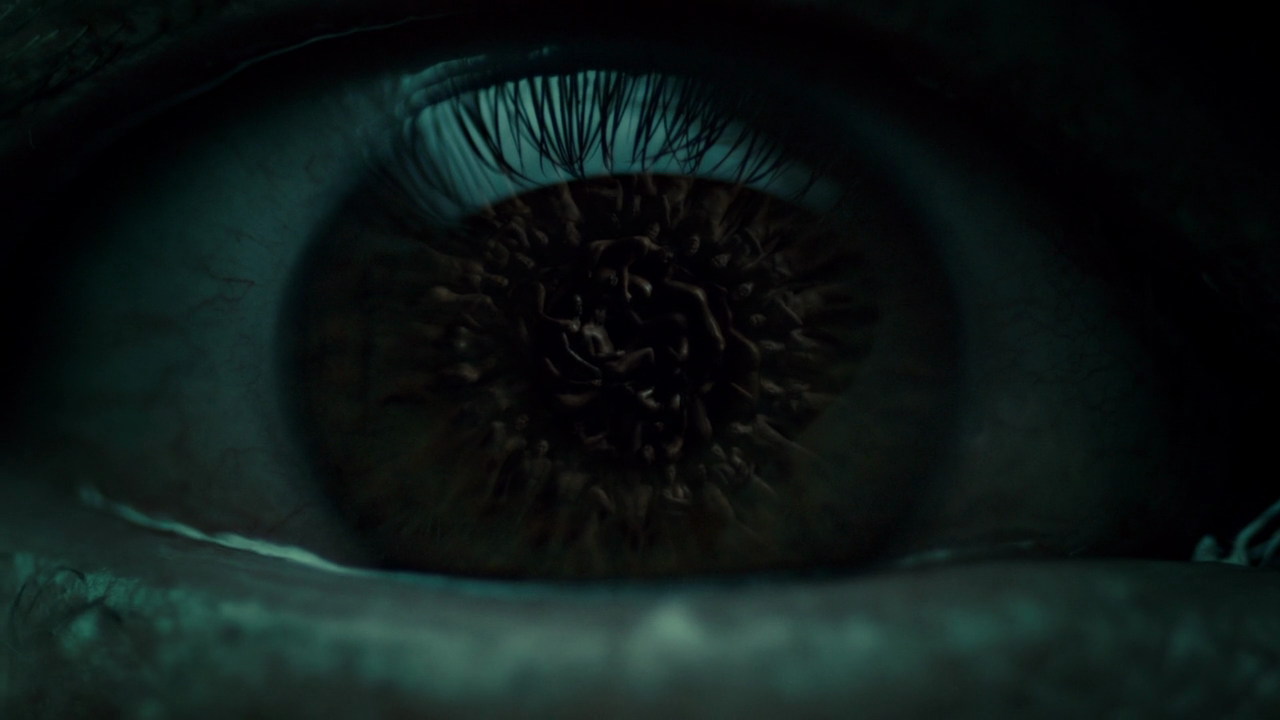

It is no doubt possible to spin a full two thousand word blog post out of this shot alone. Over a sudden intrusion of soaring choir music, Hannibal gazes down at the mural from the top of the silo, finally revealing its form as specifically an eye, gazing upwards out the silo, initially at the firmament and then, inevitably, at Hannibal. Then, just to hammer home the “it’s an eye” point, we get this reverse shot of the mural reflected in Hannibal’s eye. (Notably, no shot along these lines is called for in the script, suggesting that the dense symbolism involved is mostly there to hammer home “the mural is an eye.”) Many of the implications of this are spelled out in dialogue later in the episode, but what is perhaps most important is the way in which it forms a suddenly closed loop – the demiurge cuts off the artist’s gaze, intruding between it and the heavens.

HANNIBAL: Hello. I love your work.

Hannibal is often camp, but Mikkelsen’s sincere deadpan of this line may be its finest hour.

HANNIBAL: The eye looks beyond this world, into the next, and sees the reflection of man himself. Is the killer looking at God? A challenge of equals? “I can be as terrible as you. I can take and I can create.”

JACK CRAWFORD: Sounds like human sacrifice to me.

HANNIBAL: Not to appease, but to defy.

JACK CRAWFORD: Is it an existential crisis?

HANNIBAL: If it were an existential crisis, I would argue there wouldn’t be any reflection in the eye at all.

The key steps in fulfilling “Kaisecki”’s flash forward are not yet in place, but it’s not hard to see how Hannibal might get caught when he’s offering artist’s statements on his murders to the FBI in person.

WILL GRAHAM: I made you pliable. Molded you. Set you and sealed you where you lay. This is my design. A dead eye with vision and consciousness. I am fixed and unseeing unless someone else sees me… Someone else has. They were here. One of these things is not like the other things. One of these things just doesn’t belong. Who are you? Why are you so different from everyone else? I didn’t put you here. You… are not my design.

Will gives voice to the silenced muralist, offering an artist’s statement to contrast with Hannibal’s to Jack.

HANNIBAL: When your great eye looked to the heavens, what did it see?

MURALIST: Nothing.

HANNIBAL: Not anymore.

MURALIST: There is no God.

HANNIBAL: Certainly not with that attitude. God gave you purpose. Not only to create art, but to become it.

MURALIST: Why are you doing this to me?

HANNIBAL: Your eye will now see God reflected back. It will see you.

The other obvious reason for adding the “reflected in the eye” shot is, of course, that it makes some sense out of this final scene between Hannibal and the muralist, which otherwise fails to quite establish how sewing the muralist into the eye causes it to see him. Otherwise, however, the flashback to this scene after we’ve already figured out all the key information from it is a slightly awkward move. (It’s not surprising that this was abandoned as an episode-closing scene.)

WILL GRAHAM: I don’t know you.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: My name is Bedelia Du Maurier.

WILL GRAHAM: You’re Hannibal Lecter’s therapist. What’s that like?

A delightful first reaction on Will’s part.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: You can transform this experience. The traumatized are unpredictable because we know we can survive. You can survive this happening to you.

WILL GRAHAM: Happening to me.

GUARD: Step away from the bars. Ma’am, step away from the bars.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I believe you.

And so what is for all practical purposes a two-part premiere concludes with Will getting his first (deeply tentative, given that Bedelia is fleeing) toehold on the seeming insurmountable task of reversing Hannibal’s framing of him. Although the most interesting part is Bedelia falling into the deeply Hannibalistic rhetoric of transformation.

July 31, 2017 @ 6:18 pm

It is no doubt possible to spin a full two thousand word blog post out of this shot alone.

Are you… are you trying to get Jane to watch Hannibal?

August 1, 2017 @ 10:56 am

Given the extent to which Bedelia is manipulated by Hannibal and unable to disentangle her psyche from his devouring influence (as evidenced by Season 3) it’s sad to see her here, ensuring Will that he can transform his trauma into a new strenght while it’s clear that she has only been deluding herself thinking that she could.

August 1, 2017 @ 12:35 pm

Although it’s important to note, I think, that it’s not really Hannibal’s influence that draws her back into his orbit – it’s her curiosity. This isn’t to say that it’s not horrific (I would generally love it if everyone just left Hannibal, or if Hannibal was thrown into a black hole, alone forever), but it makes it a bit harder for me to feel sorry for her than it is in case of other characters, such as Will or Alana.

August 1, 2017 @ 1:26 pm

You’re right. She’s not an innocent victim. And yeah, at least by Season 3 she’s honest with herself about her own motivations and desires. Still, seeing her so deluded here saddened me.

I would also love for everyone to just leave Hannibal. Although I wonder if loneliness would really be so painful to him. He seems to be doing quite well while in prison in (again) Season 3.

August 1, 2017 @ 2:48 pm

Sure, but he has Alana to smirk at and he’s biding his time until Will comes back. Take away Will, the FBI, people to feed people to, people to feed to people – and he’s left with nothing that would be of any value to him.

(Unlike Aristoteles’ social animal, it is only with other people that Hannibal can be a beast and a god).

August 1, 2017 @ 12:58 pm

“the demiurge cuts off the artist’s gaze, intruding between it and the heavens.”

Thus, in true demiurge fashion, positioning himself as God (usurping both the God in heavens and the killer-as-God), who, with the completion of the mural, can now admire himself in the eye’s reflection.

This also provides some food for thought when it comes to the relationship between a work of art, the artist, and the critic. Hannibal seeks to pinpoint the presence of the author, but putting him at the centre of his creation serves only to feed Hannibal’s arrogance (the killer and Hannibal being reflections of each other, and therefore, in an alchemical sense, one and the same – building parallels between Hannibal and the murderers of the week being a trick that the show has already used numerous times).