The Proverbs of Hell 2/39: Amuse-Bouche

We’re currently $11 shy of Doctor Who Season Ten reviews on Patreon, and $31 shy of podcasts. It’s probably not quite that bad, as there are some declined pledges from March that will hopefully straighten out, but if these are things you want, please support the site by backing it on Patreon.

We’re currently $11 shy of Doctor Who Season Ten reviews on Patreon, and $31 shy of podcasts. It’s probably not quite that bad, as there are some declined pledges from March that will hopefully straighten out, but if these are things you want, please support the site by backing it on Patreon.

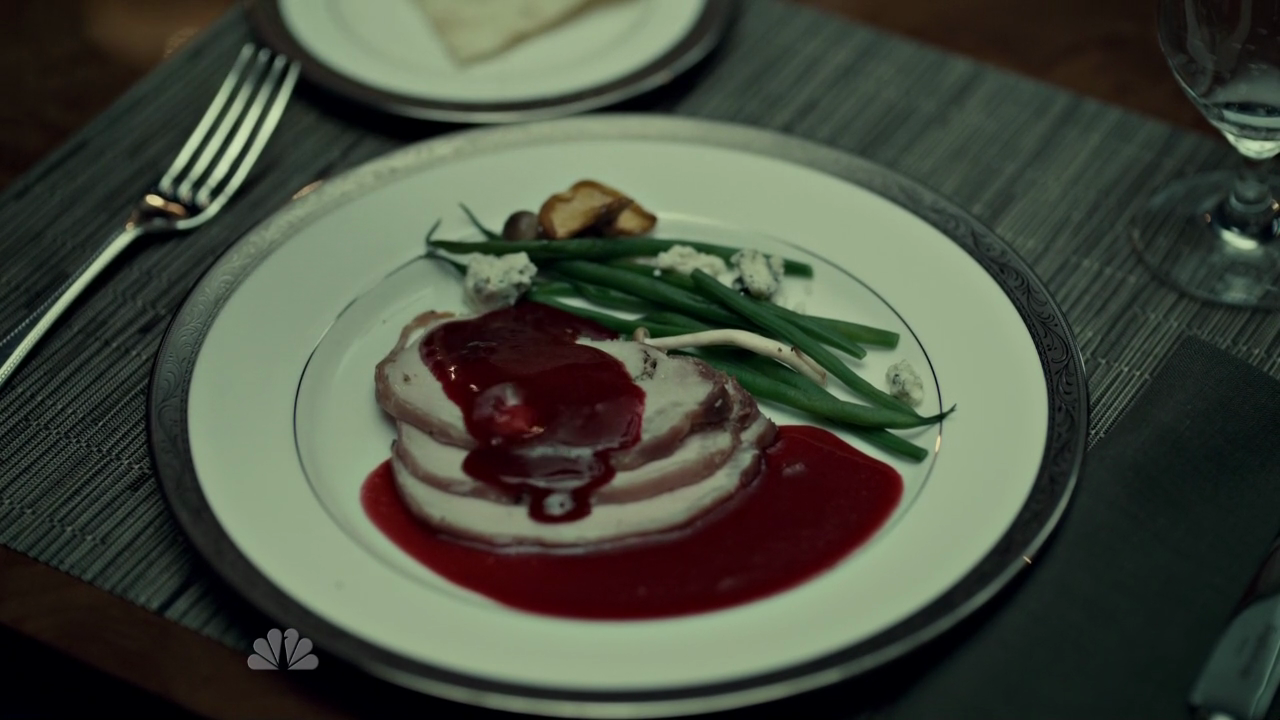

AMUSE-BOUCHE: Literally “mouth amuser,” its function is much the same as an apéritif, but it is a bite-sized food item and thus more substantial, in much the same way that this episode, liberated from the amount of setup and exposition that “Apéritif” had to do, gets to be. A stuffed mushroom cap would be an entirely appropriate choice of amuse-bouche.

The tiered concrete at which his students sit give the sense of Will having retreated back into the bone arena of his skull.

The show’s distinctive establishing shots are as important as its richly saturated color palette in creating its Chesapeake Gothic atmosphere. The time lapse establishing shots, with clouds whizzing overhead, frame what happens as taking place outside of time, in a fractured dreamscape. Fractured time is a recurring motif in the show, where it serves to indicate the blurring of internal and external landscapes. Here the process is virtually literal.

HANNIBAL: You saved Abigail Hobbs’ life. You also orphaned her. It comes with certain emotional obligations, regardless of empathy disorders.

WILL GRAHAM: You were there. You saved her life, too. Do you feel obligated?

HANNIBAL: I feel a staggering amount of obligation. I feel responsibility. I’ve fantasized about scenarios where my actions may have allowed a different fate for Abigail Hobbs.

An endearing quirk of Hannibal’s pathology is that, while he certainly will lie when it’s required of him (“Pork,” for instance.), he prefers not to. This speech is one of the most nuanced. The second two claims are reasonably straightforward – especially “I feel responsibility,” although “fantasized” is the funniest of them. The first, however, is the interesting one, simply because it is honest. Hannibal really does feel just as much paternal attachment to Abigail as Will following what happened. Where Will (somewhat wrongly) views her as something like a human version of one of his rescued dogs, Hannibal is well aware that Jack’s suspicions of her are correct, and his paternal attachment is much more similar to her actual father’s. Which is to say, he both wants her as an apprentice and potential meal.

BEVERLY KATZ: Zeller wanted to give you the bullets he pulled out of Hobbs in an acrylic case, but I told him you wouldn’t think it was funny.

WILL GRAHAM: Probably not.

BEVERLY KATZ: I suggested he turn them into a Newton’s Cradle, one of those clacking swinging ball things.

WILL GRAHAM: Now that would have been funny.

Will’s sense of humor foreshadows his affection for Hannibal, whose aesthetic in his murder tableaus is not entirely dissimilar to making a Newton’s Cradle out of the bullets that killed Garret Jacob Hobbs.

JACK CRAWFORD: Lecter gave you the “all clear.” Maybe therapy does work on you.

WILL GRAHAM: Therapy is an acquired taste I have yet to acquire but sure served your purpose. I’m back in the field.

Jack is torn between being too ruthless not to snap up the opportunity to get Will back in the field and too moral not to try to take care of Will. Here he’s confronted with the reality that Hannibal rubber-stamped Will back into the field and chooses to ignore it in the hope that Hannibal proves useful to Will despite having cavalierly tossed him into action. In fact Hannibal represents the least happy medium possible between Jack’s two desires, although it’s safe to say that Will is going to acquire the taste eventually.

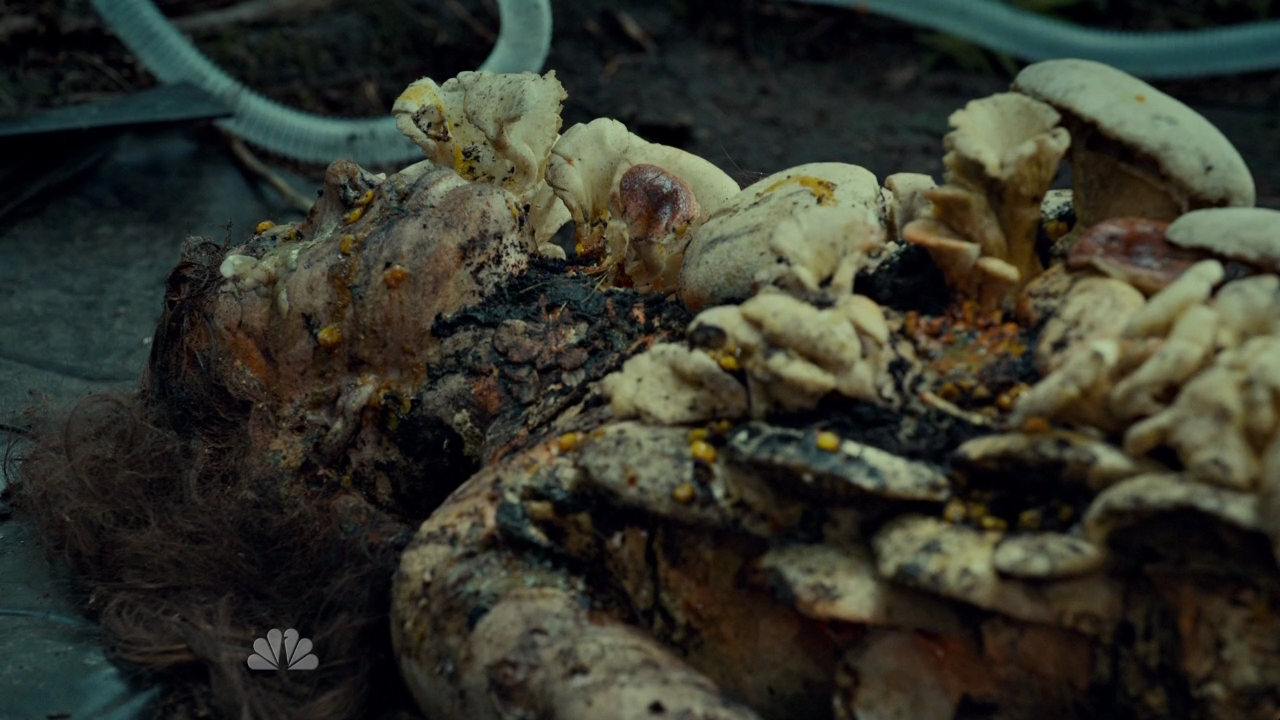

As Hannibal transitions into the somewhat awkward case-of-the-week structure it will pretend to have for its first season, it leads with an absolute stunner. Stammetz’s M.O. is brilliantly inventive and weird, and we’ll get to the ways in which it’s a brilliant choice for Hannibal specifically. But it also comes with a spectacularly unsettling visual in the form of the mostly decomposed mushroom people. The body horror involved is as intense as anything Human Centipede (a series I will never cover on Eruditorum Press, but would call the series “Incremental Progress” if I did) has ever offered, and in a way that can clear network standards and practices to boot.

This particularly outlandish choice for an initial case-of-the-week presentation further solidifies the unreality of the show. Simply put, this clearly isn’t happening in the real world.

HANNIBAL: Is it harder imagining the thrill somebody else feels killing now that you’ve done it yourself?

WILL GRAHAM: Yes.

There is considerable ambiguity over what this difficulty is, and Hannibal does not probe it further. It jars appreciably with Will’s later admission that killing Garret Jacob Hobbs felt good, a fact that seems like it should be more or less equivalent to saying that it’s easy to imagine the thrill of killing. (Or, as Hannibal and Will both put it later, a “sprig of zest.”) Two ways out of this exist. The first is to read “harder” not as performance but as emotional exertion – thinking about killing is more taxing on Will now. This is self-evidently true, and thus fairly uninteresting. The second, meatier option is to read the difficulty in imagining, whether because Will’s own thrill interferes or because his newfound appetite for killing means that the thrill feels as though it is situated in nature instead of in imagination. If killing is simply a desire of meat then it is no longer something that Will’s vision conjures into being when reading a murder: it is simply there, as much a part of the scene as the blood.

HANNIBAL: The structure of a fungus mirrors that of the human brain. An intricate web of connections.

This similarity is obvious and the source of a non-trivial number of sci-fi concepts, but crucially is based entirely on appearance. The physical structure and visual appearance of the nervous system and fungi are indeed similar, but there is no actual similarity of function. And yet this fact seems wholly irrelevant to proceedings. Stammetz’s theories are treated as being roughly as credible as Garret Jacob Hobbs’s love for Abigail. But that’s a controversial extension of human empathy, not science-defying mysticism. But consider Hannibal’s visual aesthetic and the unreality of its spaces. In the context of its gothic dreamscape, the visual resemblance is a substantive one.

Also likely is that while mushroom people can clear standards and practices, the Terence McKenna angle they actually want to go for wouldn’t cut it. On the other hand, “Œuf.”

FREDDIE LOUNDS: I’ve never seen a psychiatrist before and I’m unfortunately thorough. So you’re one of three doctors I’m interviewing. It’s more or less a bake-off.

HANNIBAL: I’m very supportive of bake-offs.

Hannibal’s propensity to covertly admit to being a cannibalistic serial killer occasionally lead him to make statements about food that are strangely suggestive without actually leading anywhere.

HANNIBAL: You’ve been terribly rude, Miss Lounds. What’s to be done about that?

This is the first time Hannibal’s method of victim selection is alluded to (the fact that Cassie Boyle once blew smoke in his face having been relegated to DVD commentary, although it was a lucky break for him that he knew a rude person in Minnesota that also fit Garret Jacob Hobbs’s pattern). Freddie, of course, is terribly rude quite often, at least by Hannibal’s standards, which makes his continual indulgence of her existence difficult to explain.

WILL: What were you gonna do to her?

ELDON: We all evolved from mycelium. I’m simply reintroducing her to the concept.

WILL: By burying her alive?

ELDON: The journalist said you understood me!

WILL: I don’t.

ELDON: Well, you would have. You would have. If you walk through a field of mycelium, they know you are there. They know you are there. The spores reach for you as you walk by. I know who you’re reaching for. I know. Abigail Hobbs. And you should have let me plant her. You would have found her in a field, where she was finally able to reach back.

Eldon’s pathology, based, as Hannibal surmises earlier in the episode, on the resemblance between fungus and the human brain, is hazily defined, essentially sketched out entirely in the disjointed monologue Stammetz gives in this scene. Nevertheless, it’s a beautifully multilayered idea. The notion of reaching and connecting people ties directly to Will’s empathy, which is of course what leads Stammetz to target Abigail. But equally important is the fact that Stammetz uses food to make the connection. In an episode whose real purpose is to begin to establish the connection between Will and Hannibal, Stammetz is an extremely apt choice of killers.

WILL GRAHAM: I thought about killing him. I’m still not entirely sure that wasn’t my intention pulling the trigger.

HANNIBAL: If your intention was to kill him, it’s because you understand why he did the things he did. It’s beautiful in it’s own way. Giving voice to the unmentionable.

Hannibal’s yearning to connect with Will over the aesthetics of murder is touching. But “giving voice to the unmentionable” is an atypically lame summary of what Stammetz’s work involved. Sure, the possibilities of new communication were central to his gardening, but the idea that he was revealing some gothically suppressed truth is a stretch. In this regard, Hannibal is projecting on Stammetz as much as he is on Will.

HANNIBAL: It wasn’t the act of killing Hobbs that got you down, was it? Did you really feel so bad because killing him felt so good?

(pause)

WILL GRAHAM: I liked killing Hobbs.

HANNIBAL: Killing must feel good to God, too. He does it all the time, and are we not created in his image?

WILL GRAHAM: Depends who you ask.

HANNIBAL: God’s terrific. He dropped a church roof on thirty-four of his worshippers last Wednesday night in Texas, while they sang a hymn.

WILL GRAHAM: Did God feel good about that?

HANNIBAL: He felt powerful.

Taken from Hannibal’s letter to Will late in Red Dragon, this is one of the show’s bolder uses of the books, burning off a fairly iconic moment as the closer to its second episode. The show’s relationship with God is an interesting one. The natural gravity of Hannibal is towards Milton’s Satan, and the show finds itself inexorably drawn towards Christian iconography. On the other hand, the show is decidedly not Christian, and its vision of God is largely established here. It’s not a deistic, distant God – he dropped the roof, as opposed to letting it fall. Rather, it is one of almost malevolent indifference/Otherness. Hannibal actively distinguishes feeling powerful from feeling good, preventing the straightforward reading of an actively evil God who is motivated by a desire for power. And yet God’s reason for killing thirty-four people in Texas remains unknown and unknowable.

Although Hannibal has some ideas.

April 3, 2017 @ 9:29 am

I seem to recall that we threw around the idea of Hannibal as a gnostic show in our Shabcast about it. In at one strand of gnosticism, there are two gods – and it’s the evil one who created this evil world we live in.

April 3, 2017 @ 10:17 am

My belief is that the gnostic god of the show is Hannibal himself – after all, he is at the centre of it, bending everything around him and manipulating people to fit his design. He just likes to think of himself as Satan rebelling against some other, unseen god – not unlike populist millionaires fashioning themselves as anti-establishment figures.

April 3, 2017 @ 11:42 am

Loving this series. I think Hannibal’s thing about “eating the rude” is not something he’s very consistent about, but he’s attached to this picture of himself, so when needed lies to himself about who is or is not rude. This reminds me of Malcolm Tucker on “The Thick of It,” who makes a big deal of being abusive to politicians and kind to the common man, but is quick to blow up at a cab driver nonetheless. I’m sure he excuses this as a rare lapse from his code.

April 3, 2017 @ 1:45 pm

Something that the show kind of lets pass outside of this episode, but is definitely in the first two or three movies, and the books, is Hannibal’s odd lapses into being very American – “God’s terrific”, a very American phrasing, though of course one that relies on the double meaning. A British English speaker might be more likely to say “God’s fantastic”, or an Irish person might, with their tongue in their cheek, say “God’s grand”. “Terrific” is a very Middle American word somehow, and Hannibal’s use is at least as much the Middle American meaning of the term as a positive as the older sense.

April 3, 2017 @ 4:36 pm

But Hannibal isn’t supposed to be English or Irish, is he? He’s Lithuanian!

We obvioulsy don’t know what places he’s lived in before Baltimore (aside from Florence, obviously), but if you assume he hasn’t spent much time in the rest of Anglosphere, it absolutely makes sense for him to speak American english.

April 4, 2017 @ 8:02 pm

It always struck me as a double-meaning? For the audience if nothing else (maybe the word play plays better in text?) There’s the modern positive connotation of terrific as “great” or “very good” but as an educated man, a non-native English speaker, and one who is fond of double meanings, I’m sure Hannibal is also aware of terrific’s etymology: from the Latin terrificus (“causing terror”), from terrere (“to frighten, terrify”). Terror, terrific. The earliest or one of the earliest citations of terrific is from Milton’s Paradise Lost, in fact—used to describe the Serpent in the Garden.

“Frighteningly great” might be a good middle road translation to this particular terrific?

April 3, 2017 @ 4:54 pm

I’m beginning to suspect I’ll have to rewatch the series before reading these posts. The series seems to be littered with meaningful foreshadowing. And while it probably is obvious that everything about Abigail becomes more multi-layered on a re-watch, the joke about the Newton’s Cradle is an excellent example of something that becomes thematically resonant on a rewatch, but which you would never remember if you didn’t.

The fughi murderer was in many ways a perfect hook for the series! It not only demonstrates Hannibal’s gorgeously morbid aesthetic sense, but it also invites the audience to feel empathic towards the act of murder. Eldons “vision” isn’t obviously meant to be logical, but at the same time it’s very understandable. His monologue is not only establishing killing as an artistic action, but also as an empathic and philosophical action. The case is designed to make us ask the exactly the right questions to lure us deeper into Hannibal’s trap… world.

April 5, 2017 @ 2:52 am

A Newton’s Cradle, of course, would be an ideal spot to catch some Newton’s Sleep…