Unearthing Review

Well, I’ve just had one of the most magical experiences of my life.

Well, I’ve just had one of the most magical experiences of my life.

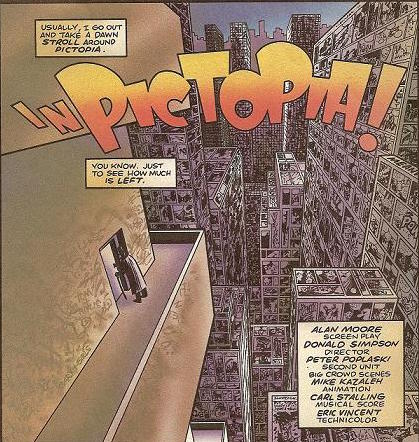

Some context – a film version of Alan Moore’s Unearthing is dropping later this morning. I was given a screener copy, and just finished watching it. It is absolutely amazing. If you have never experienced Unearthing, it is unquestionably the version to go for. If you have experienced it before, it offers a substantial upgrade to all previous versions and is very probably worth revisiting; certainly I found it a tremendously rewarding experience.

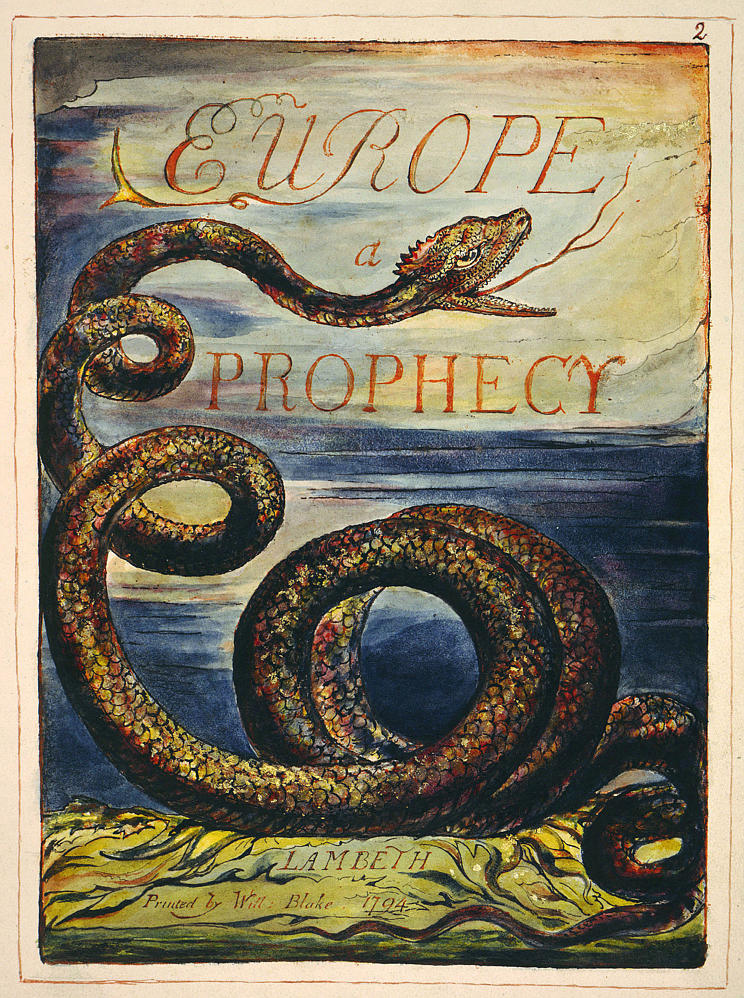

There are ways in which yours will not match mine. It will not, for instance, include you belatedly realizing that you got the idea of printing an edition of your book published on old-fashioned printer paper from the transcript included with the old box set of Unearthing as an audio performance. Nor the sequence where you are floored by a snake-based description of philosophical horror that repeatedly echoes and parallels your book’s major points, a beautiful and welcome reminder that your great work can probably be encapsulated in a clod of dirt in a Northampton back garden. Still, it won’t be hard to see how the work could affect someone like that. It’s that good, and that visibly powerful a piece of magic. Of course it’s going to resonate weirdly with the world. That’s the point.

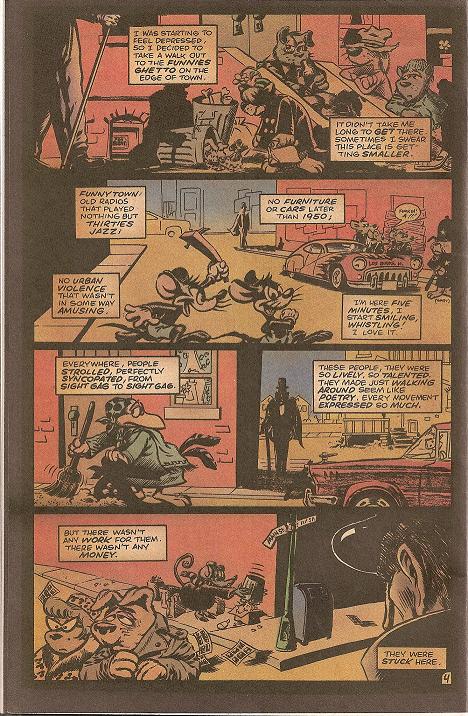

Unearthing is the story of Steve Moore, as told by Alan Moore. A prehumous eulogy, in many ways deliberately, Moore relates the strange life of his best friend, who was born in the house on Shooter’s Hill in London where he died, who taught the greatest English-language writer ever to work primarily in the medium of comics how to write a script, whose own career spanned decades, its fingerprints all over the history of British comics, who was beyond that a noted I Ching scholar, and who conducted a lengthy sexual affair with the moon goddess Selene.

Moore does not bury the lead, although he does build to it. Still, Unearthing is about this last bit. And the other bits, and many besides, but mostly the last bit. It is handled with a deft literary irony – a claim vouched for entirely by the author, who is ostentatiously present, a hypnotic baritone and looming beard that repeatedly appears on screen while the tale’s subject appears only in flickered inserts, played by an actor. An author who announces his entrance to the narrative with relish and fanfare, positioning himself as arbiter of the great “is Steve Moore mad or is this really magic” debate to an audience who knows full well that there is only one possible answer that he would ever give. It’s a delightfully, deliberately ludicrous claim – a man who worships a glove puppet promising us all that his best friend’s girlfriend is a Greek goddess and blue.

You’ll believe every word.

Much of this is because the narrator’s appearances, though dramatic and coming at highly charged moments of the tale, are nevertheless cameos. For most of the piece, Moore stands at polite distance, affecting to tell his friend’s story as he would want it told.…

…

…

Last War in Albion this afternoon.

Last War in Albion this afternoon.

Today’s image is of Magneto killing some Nazis. Because I like that.

Today’s image is of Magneto killing some Nazis. Because I like that. A-Force #5

A-Force #5