Killing for Art (Book Three, Part 36: The Brotherhood of Dada, Dada)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Grant Morrison’s early issues of Doom Patrol showed a clear debt to avant garde art of many kinds.

“They would die for art in any case. Killing for art was far easier.” -Kieron Gillen, The Wicked + The Divine

Morrison, however, embraced strangeness for its own sake, turning to these techniques simply because in their view Doom Patrol should be weird and these were the weird things they liked. This was not quite the same thing, and would be an approach that came with perils. Equally, when it worked it was spectacular. Their second major arc, beginning in issue #26, was a tour de force that served in many ways to exemplify the appeal of their take on the book. At the heart of it was their reworking of the Brotherhood of Evil, a recurring set of Doom Patrol villains dating back to Doom Patrol #86 in 1964, the first issue after the title renamed itself from My Greatest Adventure. As with much of Arnold Drake’s run, this group had an endearing strangeness to them—its first appearance offered the rare supervillain team that had a disembodied brain in a vat, a talking gorilla, and a giant robot. The latter of these was named Rog, and was stolen by a man named Eric Morden as part of his efforts to join the group. The Brotherhood of Evil made a second attempt to destroy the Doom Patrol in the very next issue, and continued to appear throughout the original run of Doom Patrol with an ever-shifting membership (Madame Rouge, who eventually killed the Doom Patrol, was one of its original members, and General Immortus eventually joined), but Eric Morden vanished after that first appearance without further mention.

In issue #26, however, Morrison revealed that the mysterious figure who had been lurking around the edges of the previous few issues in a series of one and two page scenes was none other than Eric Morden, who explains, in a gloriously unreconstructed supervillain monologue, that he went into hiding in Paraguay after enraging the talking gorilla Monsieur Mallah and the disembodied brain The Brain. There he took up an offer from a Nazi scientist to make him a new man, a process that involved paralyzing him and leaving him in a sensory depravation tank for three days, where he went gradually insane and then, in a climactic moment, found himself reborn as “the spirit of the twenty-first century, the abstract man. The virtual man. The notional man.” Or, as he ultimately decided on. Mr. Nobody—a strange and cartoonish abstraction of a human figure shown only in two dimensional silhouette. And having recruited a new team he dubbed them not the Brotherhood of Evil but the Brotherhood of Dada.

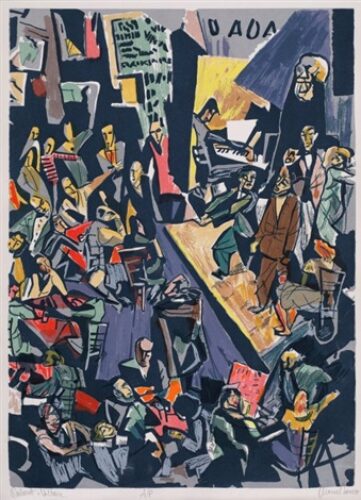

Dada was part of the modernist rush of new and radical artistic movements—a cousin of Futurism and Cubism. But more than any of these, its approach was one that saw forward and anticipated the postmodern turn. Its best known practitioner is probably Marcel Duchamp, who rebranded his existing practice of “anti-art” to Dada after moving to New York City in the wake of World War I.…