Chapter Five: The Way Our Heads Thunder (Fearful Symmetry)

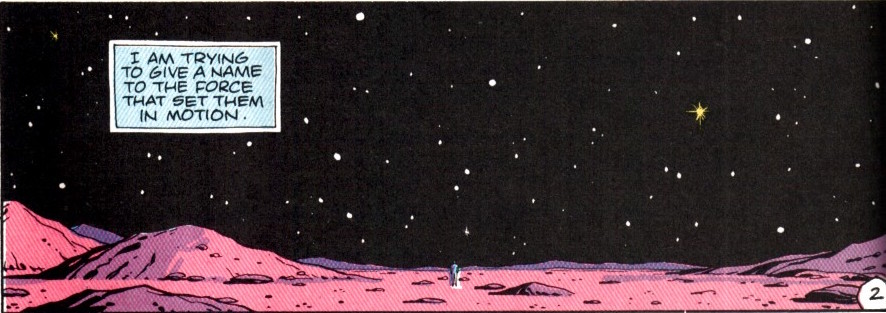

_p01_(comichost-dcp).jpg) Moore’s disorientation and confusion in the wake of Watchmen is wholly understandable. Even reading Watchmen is, at times, enough to generate a sense of dazed exhaustion. And this is very much the point – an effect consciously generated by Moore’s use of the dense uniformity of the nine-panel grid. As Kieron Gillen puts it in Kieron Gillen Talks Watchmen, “if we’re talking about the many icons of Watchmen, [the nine-panel grid] is the invisible one. It underlies everything. We’re to watch these little boxes – hundreds of them – and make sense by combining them all into a larger piece of meaning. Watch,” he says, and snaps his fingers to cue his projectionist to advance his PowerPoint to a shot of Ozymandias watching his wall of television screens. Gillen talks about the comic as a “clockwork machine” in which “everything is predetermined. The forces that are put into motion mean this… the clock will carry on ticking, and if you read Watchmen enough you’ll know what the next tick is.” Gillen, here, is talking about the comic’s famously ambiguous ending, making a strong case that in fact there is only one possible “next step” for the book to take, and that the inevitable momentum of that step hangs impermeably over the entire work, which is in turn what Morrison speaks of when he talks about how the god of Watchmen is always shoving his cock in the reader’s face.

Moore’s disorientation and confusion in the wake of Watchmen is wholly understandable. Even reading Watchmen is, at times, enough to generate a sense of dazed exhaustion. And this is very much the point – an effect consciously generated by Moore’s use of the dense uniformity of the nine-panel grid. As Kieron Gillen puts it in Kieron Gillen Talks Watchmen, “if we’re talking about the many icons of Watchmen, [the nine-panel grid] is the invisible one. It underlies everything. We’re to watch these little boxes – hundreds of them – and make sense by combining them all into a larger piece of meaning. Watch,” he says, and snaps his fingers to cue his projectionist to advance his PowerPoint to a shot of Ozymandias watching his wall of television screens. Gillen talks about the comic as a “clockwork machine” in which “everything is predetermined. The forces that are put into motion mean this… the clock will carry on ticking, and if you read Watchmen enough you’ll know what the next tick is.” Gillen, here, is talking about the comic’s famously ambiguous ending, making a strong case that in fact there is only one possible “next step” for the book to take, and that the inevitable momentum of that step hangs impermeably over the entire work, which is in turn what Morrison speaks of when he talks about how the god of Watchmen is always shoving his cock in the reader’s face.

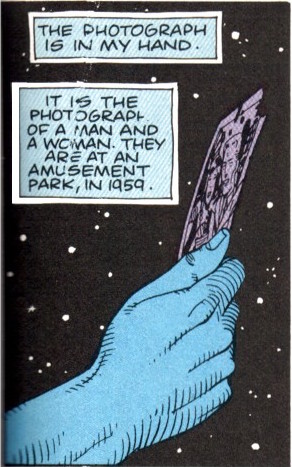

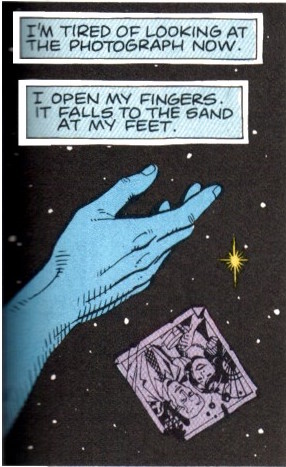

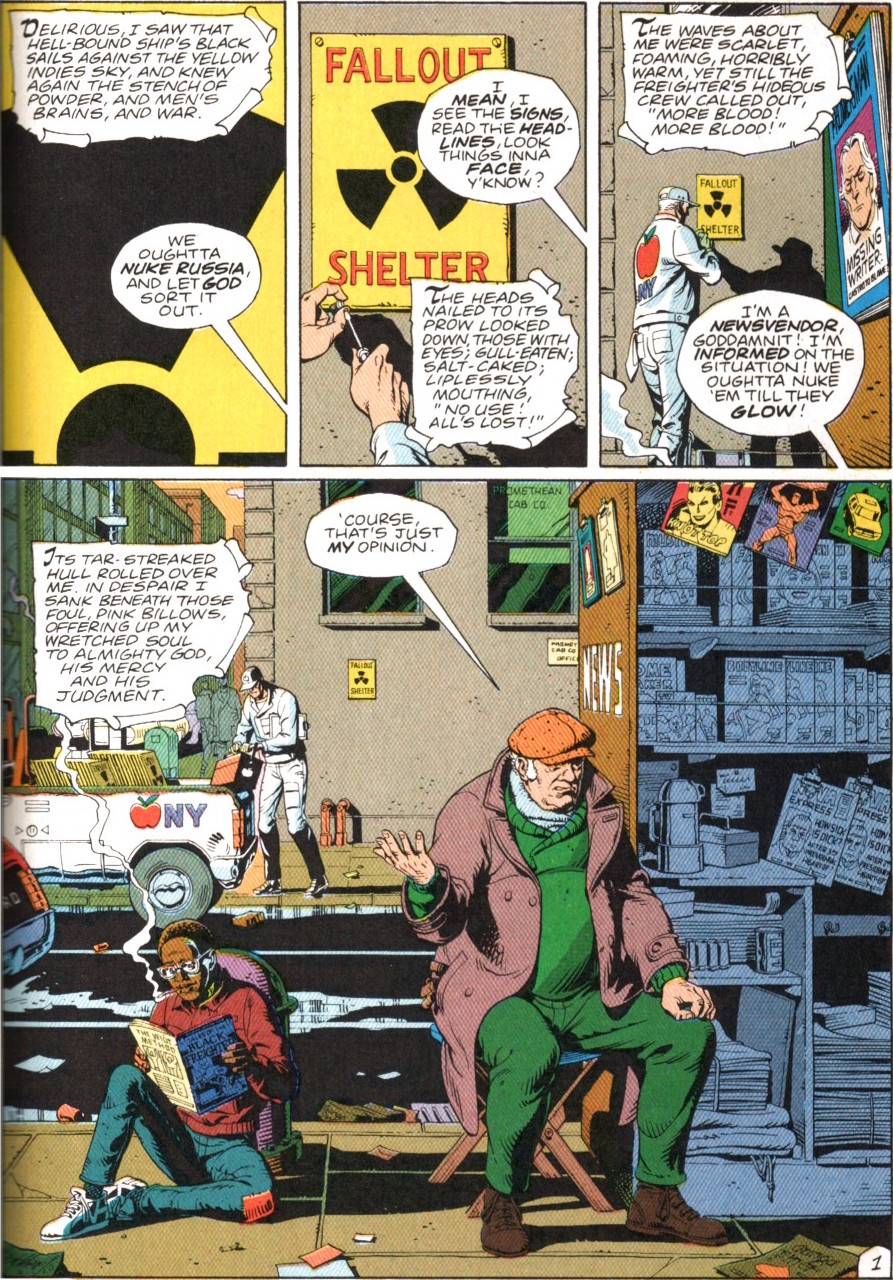

Nowhere is this sense clearer, perhaps, than Watchmen #5, the famed “Fearful Symmetry” chapter. It has been noted by many that Moore’s focus and enthusiasm for a project often wanes over the course of it. If so, it is hard not to see “Fearful Symmetry” as a crucial turning point in the comic. Moore has spoken in interviews of how the third issue marked the point where he and Gibbons really mastered the technique of juxtaposition that would serve as one of the major engines of the book. Similarly, issue #4, “Watchmaker,” is a virtuosic and experimental piece playing with the nature of time, in which Moore, channeling Nicholas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, depicts the life of Dr. Manhattan as a simultaneously occurring eternity. And with “Fearful Symmetry” Moore reaches the formal zenith of the work, if not of his entire career. In a real sense it is impossible to imagine that Moore could devote the focus and attention that “Fearful Symmetry” required to any subsequent issue. In terms of Watchmen as a set of storytelling techniques – the grounds on which Moore, at least, has long been inclined to judge it – “Fearful Symmetry” marks the tale’s end. On top of that, its release in October of 1986 marks the last issue of Watchmen to come out prior to the explosion of the ratings controversy that would result in Moore’s acrimonious departure from DC. Moore would, of course, have been ahead in actually writing the book at this point, but the point stands – not long after “Fearful Symmetry” came the point where Moore began actively distancing himself from his DC superhero work.…

It is January, 1988. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and writing the introduction to the collected edition of Watchmen. His relationship with the publisher is in tatters, a fact he alludes to only vaguely when he notes that it is “the very last work that I expect to be doing upon Watchmen for the foreseeable future.” He looks back to 1984, when the idea originated, and the giddy enthusiasm of it all. And yet there is something he cannot quite locate in this. He notes that at the start “we wanted to do a novel and unusual super-hero comic that allowed us the opportunity to try out a few new storytelling ideas along the way. What we ended up with was substantially more than that.” But he cannot pin down the transition. Instead he describes a growing realization of the story’s complexity and scale, but without a sense that the realization had an end point. Instead, “there was the mounting suspicion (at least on my part) that we might have bitten off more than we could chew, that we might not be able to resolve all these momentous strands of narrative and meaning that seemed to be springing up wherever we looked, that we might be left at the end of the day with a big, messy, steaming bowl of semiotic spaghetti.” But even now, in 1988, Moore is lost in the process, saying that it is only now, in writing the introduction, that he realizes “how dazed a state I’d spent that year in, as if I’d been slam dancing with a bunch of rhinos and the concussion was only just starting to clear up,” a claim that oddly undercuts itself; the daze clearly extending beyond the year, simultaneously located “now, twelve months after” he finished the final script and in the past, as indicated by the past tense in the concussion metaphor.

It is January, 1988. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and writing the introduction to the collected edition of Watchmen. His relationship with the publisher is in tatters, a fact he alludes to only vaguely when he notes that it is “the very last work that I expect to be doing upon Watchmen for the foreseeable future.” He looks back to 1984, when the idea originated, and the giddy enthusiasm of it all. And yet there is something he cannot quite locate in this. He notes that at the start “we wanted to do a novel and unusual super-hero comic that allowed us the opportunity to try out a few new storytelling ideas along the way. What we ended up with was substantially more than that.” But he cannot pin down the transition. Instead he describes a growing realization of the story’s complexity and scale, but without a sense that the realization had an end point. Instead, “there was the mounting suspicion (at least on my part) that we might have bitten off more than we could chew, that we might not be able to resolve all these momentous strands of narrative and meaning that seemed to be springing up wherever we looked, that we might be left at the end of the day with a big, messy, steaming bowl of semiotic spaghetti.” But even now, in 1988, Moore is lost in the process, saying that it is only now, in writing the introduction, that he realizes “how dazed a state I’d spent that year in, as if I’d been slam dancing with a bunch of rhinos and the concussion was only just starting to clear up,” a claim that oddly undercuts itself; the daze clearly extending beyond the year, simultaneously located “now, twelve months after” he finished the final script and in the past, as indicated by the past tense in the concussion metaphor. A similar temporal ambivalence exists in the previously discussed description of how his “nostalgia for the [superhero] genre cracked and shattered somewhere along the way and all the sweet old musk inside just leaked out and evaporated,” a statement in which Moore is clearly lying, albeit as much to himself as the reader, the description of the “sweet old musk” evoking precisely what he says he has lost, so that the sentence offers the very experience it exists to reject. Moore casts superheroes away, but in doing so only draws them back in, a tension implicit in the very idea of nostalgia, which is of course an intense feeling for a thing that one is not actually experiencing at the time. He is nostalgic for his nostalgia, relishing in the scent of its memory even as he pushes the genre away, grimly certain in the necessity of all his burnt bridges. The “disappointment when I learned that we couldn’t use the Charlton characters after all” mixes in his prose with the bitter taste of his falling out with DC.

A similar temporal ambivalence exists in the previously discussed description of how his “nostalgia for the [superhero] genre cracked and shattered somewhere along the way and all the sweet old musk inside just leaked out and evaporated,” a statement in which Moore is clearly lying, albeit as much to himself as the reader, the description of the “sweet old musk” evoking precisely what he says he has lost, so that the sentence offers the very experience it exists to reject. Moore casts superheroes away, but in doing so only draws them back in, a tension implicit in the very idea of nostalgia, which is of course an intense feeling for a thing that one is not actually experiencing at the time. He is nostalgic for his nostalgia, relishing in the scent of its memory even as he pushes the genre away, grimly certain in the necessity of all his burnt bridges. The “disappointment when I learned that we couldn’t use the Charlton characters after all” mixes in his prose with the bitter taste of his falling out with DC. But more important than the way these things slide away from him is what he is looking for in amidst the rubble: “any sort of perspective upon what it was we actually did.”…

But more important than the way these things slide away from him is what he is looking for in amidst the rubble: “any sort of perspective upon what it was we actually did.”… Part of the difficulty in tracking the fallout of Moore’s split with DC is simply that it’s so extensive. Once the rupture began it spread quickly, fueled in no small part by Alan Moore’s tendency to, as he’s put it, burn his bridges when reacting against something so as to make sure he’s never tempted to go second guess himself. But in this case the fractal repetition of Moore’s grievances with DC have served to make the initial issues harder to see, to the point where the standard wisdom is that Moore’s break with DC came over a dispute in the handling of the Watchmen trade paperback when, in reality, he had made his decision not to accept any new work from DC in January of 1987, eight months before the trade paperback even came out, and five months before Moore was actually done working on it. This decision came during a wider dispute about DC’s proposed creation of a ratings system for their comics. And even that point is not a single discrete cause that can be separated out from all of the others and identified as the original, true rift, but at best the third issue to arise between Moore and DC in quick succession.

Part of the difficulty in tracking the fallout of Moore’s split with DC is simply that it’s so extensive. Once the rupture began it spread quickly, fueled in no small part by Alan Moore’s tendency to, as he’s put it, burn his bridges when reacting against something so as to make sure he’s never tempted to go second guess himself. But in this case the fractal repetition of Moore’s grievances with DC have served to make the initial issues harder to see, to the point where the standard wisdom is that Moore’s break with DC came over a dispute in the handling of the Watchmen trade paperback when, in reality, he had made his decision not to accept any new work from DC in January of 1987, eight months before the trade paperback even came out, and five months before Moore was actually done working on it. This decision came during a wider dispute about DC’s proposed creation of a ratings system for their comics. And even that point is not a single discrete cause that can be separated out from all of the others and identified as the original, true rift, but at best the third issue to arise between Moore and DC in quick succession. Certainly Moore would have had little reason to see DC as essential to his career. He had, after all, succeeded with essentially every company he’d worked with.…

Certainly Moore would have had little reason to see DC as essential to his career. He had, after all, succeeded with essentially every company he’d worked with.… This is, perhaps, why so much ink has been spilled within the War on attempts to argue that this gap, in effect, does not exist – that Watchmen can be understood purely, or at least primarily, in terms of its influences, thus allowing those living in its wake to exist as though they are free from its vast and monolithic splendor. It is, after all, the easier option; it does not require staring too long at the cavernous depths within. It gives the comforting illusion that Watchmen is, at its heart, an easily solved mystery – a question with a definite answer. Nothing could be further from the truth, but for those who would otherwise find themselves caught in its blast, reduced to mere shadows cast by its incinerating radiance the idea that the book is simply some inevitable consequence of what came before is a useful delusion.

This is, perhaps, why so much ink has been spilled within the War on attempts to argue that this gap, in effect, does not exist – that Watchmen can be understood purely, or at least primarily, in terms of its influences, thus allowing those living in its wake to exist as though they are free from its vast and monolithic splendor. It is, after all, the easier option; it does not require staring too long at the cavernous depths within. It gives the comforting illusion that Watchmen is, at its heart, an easily solved mystery – a question with a definite answer. Nothing could be further from the truth, but for those who would otherwise find themselves caught in its blast, reduced to mere shadows cast by its incinerating radiance the idea that the book is simply some inevitable consequence of what came before is a useful delusion.

It’s September 30

It’s September 30