Nice new bit of audio content for you today, mainly on the subject of guys called Orson.

Nice new bit of audio content for you today, mainly on the subject of guys called Orson.

From the Wrong With Authority stable, a commentary track for Orson Welles’ undervalued late masterpiece F for Fake, featuring myself and Daniel Harper. Download or listen HERE.

This commentary is basically a spin-off from an episode of They Must Be Destroyed on Sight in which I guested to chat about the same film – here. TMBDOS also recently did an episode on Welles’ finally-completed final film, The Other Side of the Wind, here.

Plus, we recently released a podcast in which Daniel and Kit chatted about Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, and somehow managed to find new angles on it, despite it being one of the most discussed texts on the internet. Download or listen HERE.

Also, if you haven’t listened to the Wrong With Authority’s third ‘Trumpism’ episode, recorded after the mid-terms, but feel like subjecting yourself to five hours of our self-therapy, that’s here.

On the subject of Wrong With Authority, we still have two great new episodes in the can, being edited, and slated to be released soon (hopefully). There’s our next proper full WWA episode, hosted by Daniel this time, which will tackle D. W. Griffiths’ racist alleged-masterpiece of early American silent cinema Birth of a Nation, and a Consider the Reagan commentary on James Cameron’s The Terminator. Holly joins the team for both. Look out for those.

Speaking of Holly, people should definitely check out her new seasonal podcast series So Here It Is, in which she is joined by a succession of guests to chat with her about the tracks in the British Christmas music canon. One of the guests who has already been on is our friend Andrew Hickey, whose own new podcast series, A History of Pop Music in 500 Songs, is another absolute must.

(Oh, and I haven’t forgotten that I was meant to be reposting the Doctor Who commentary tracks I recorded with El. I’ll get back to that, probably in the new year.)

In other me-news, I’ve recently had something of a posting spurt over at my Patreon, and people who sponsor me for as miniscule a goddamn pittance as one measley dollar a month goddammit can exclusively access forthcoming posts of mine (fucking looooong ones too) on things like the TV show Legion (which I’ve perversely decided to find fascinating), Doctor Who and Brecht’s ‘Epic Theatre’, and Marx’s theory of capitalist crisis… as well as an audio snippet from the WWA episode we did on Anonymous in which me and the gang get drawn into a little chat about the ‘New Atheists’.

…

Continue Reading

Owing to a decided – and entirely understandable – lack of enthusiasm for the project from anyone else, I embarked on a solo commentary on the 1984 movie version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, starring George C. Scott as Scrooge. Luckily, I’m quite capable of wittering on for 90 minutes unassisted.

Owing to a decided – and entirely understandable – lack of enthusiasm for the project from anyone else, I embarked on a solo commentary on the 1984 movie version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, starring George C. Scott as Scrooge. Luckily, I’m quite capable of wittering on for 90 minutes unassisted.

There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes.

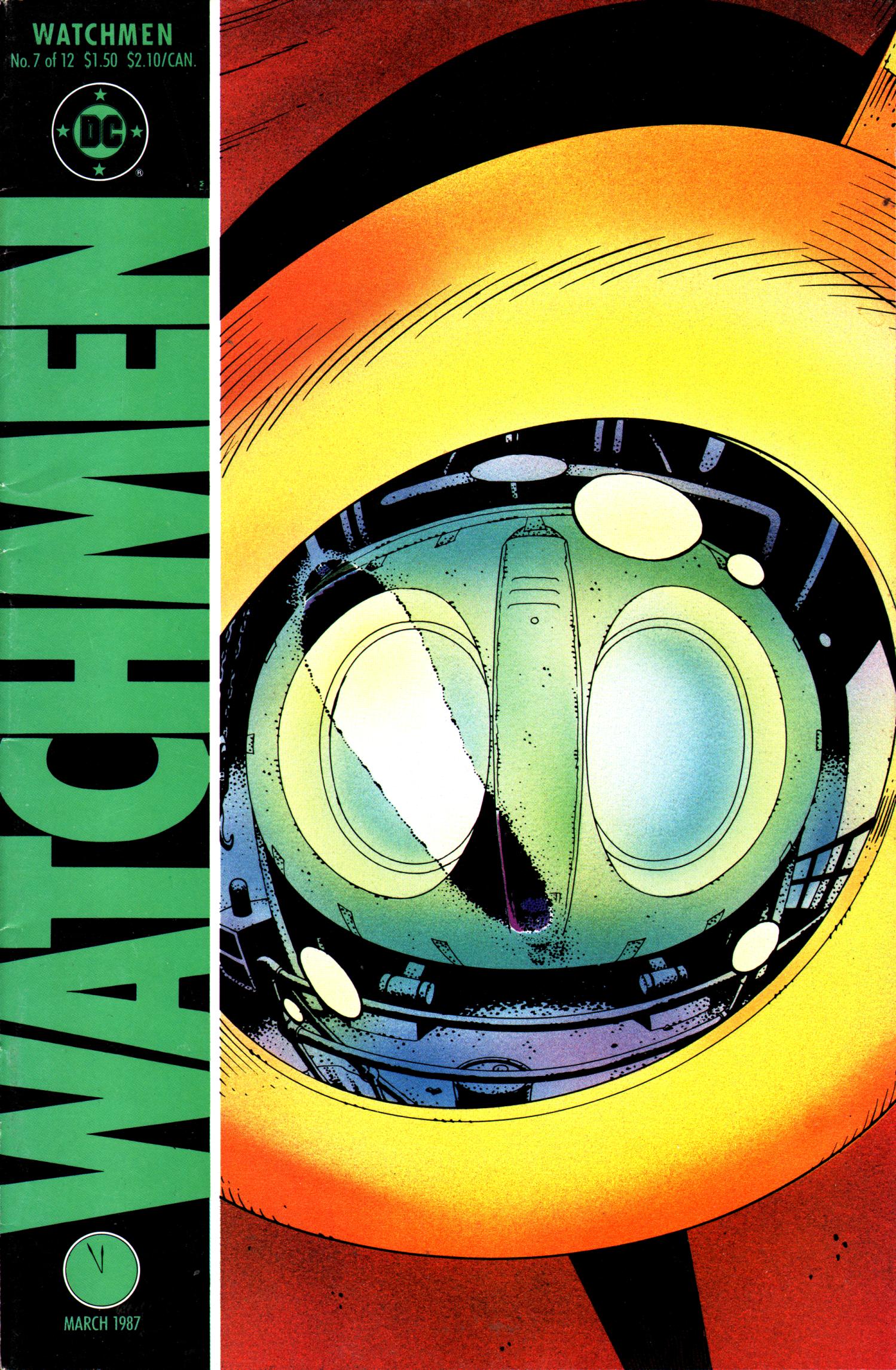

There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes. The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl.

The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl.

Parts of the below were developed in conversation with Niki Haringsma, whose Black Archive on ‘Love & Monsters’ is forthcoming, and who was recently heard

Parts of the below were developed in conversation with Niki Haringsma, whose Black Archive on ‘Love & Monsters’ is forthcoming, and who was recently heard  Nice new bit of audio content for you today, mainly on the subject of guys called Orson.

Nice new bit of audio content for you today, mainly on the subject of guys called Orson.