The Ron Paul Revolution (Part 1)

In my opinion, any account of the rise of the alt-right, especially one which emphasizes the role of libertarianism, and thus the distal causal role of the Austrian School of economics, must begin with Ron Paul.

In my opinion, any account of the rise of the alt-right, especially one which emphasizes the role of libertarianism, and thus the distal causal role of the Austrian School of economics, must begin with Ron Paul.

In his essay ‘On Social Sadism’, published in the journal Salvage, China Miéville recounts an occasion when

[a]t a debate between Republican candidates in September 2011, Wolf Blitzer, the chair, mooted the case of a hypothetical thirty-year-old uninsured man who becomes sick. ‘[C]ongressman,’ Blitzer asks Ron Paul, ‘are you saying that society should just let him die?’

‘Yeah!’ comes a shout from the audience. A smattering of applause. The shout is repeated, and again, and the applause grows.

Paul retired from politics in 2013, but his shadow is long on the libertarian Right. After the above exchange, Paul – a former medical doctor and a fervent libertarian, indeed a ‘paleolibertarian’, a follower of the syncresis of libertarianism and far-right conservatism invented by Murray Rothbard and Lew Rockwell – suggested that the hypothetical man in the question should have a private medical plan. “We’ve given up on this concept that we might assume responsibility for ourselves, that our neighbors, our friends, our churches would do it,” opined Paul sententiously. He later clarified his position on Twitter saying that “[t]he individual, private charity, families, and faith based orgs should take care of people, not the government.” Recognisably a species of the same weaselly ‘Big Society’ argument employed around the same time by the coalition government in the UK as its Tory leaders tried to find a way to reconcile lethal austerity with their claim to no longer being ‘the nasty party’. Charity as a moral imperative, supplanting the need for socialised care. Chilly Victorian workhouse morality, dressed up as a plaintive cry for us all to be nicer to each other (so no surplus value has to be diverted anywhere useless). Paul’s iteration has a more overtly Christian flavour, as befits American politics, and a tang of his ostensible anti-authoritarianism, but it boils down to the same thing: a thoroughly neoliberal impulse to relieve the state of its responsibilities to its subjects, while framing this as asking the subjects to take back control of their responsibilities. In Cameron’s version, the emphasis was more on countering a supposed culture of dependence, whereas in Paul’s the emphasis was more on encouraging individual liberty. But we’re splitting hairs. The difference here is, as I say, a matter of emphasis. And we learn a lot from the fact that the same argument, with tweaks for tone, can be advanced from what are supposedly ideologically distinct varieties of conservatism.

Neoliberalism is a broad church. This has been true since its birth, since the Mont Pelerin Society included Austrians and monetarists, neoconservatives and ordoliberals. It is key to its success. The collaboration and cross-pollination of ideas speaks to its status as a class project rather than a distinctly ideological one. It’s one of the tragic ironies of history that the revolutionary projects of the ruling class are (or at least can be) marked by tolerance and cooperation between different branches of ruling class ideology, whereas the revolutionary projects of the working class have tended to be marked by the exact opposite.…

THE WRATH OF THE LAMB: Reframing the title scheme for the back half of the season away from “Blake paintings” and towards “lines from Revelation,” and not entirely honestly. The title drop in the proceeding episode forces single vision, such that it can only refer to Will’s vengeance against Hannibal, although it’s not as though it would have been long on ambiguity without that.

THE WRATH OF THE LAMB: Reframing the title scheme for the back half of the season away from “Blake paintings” and towards “lines from Revelation,” and not entirely honestly. The title drop in the proceeding episode forces single vision, such that it can only refer to Will’s vengeance against Hannibal, although it’s not as though it would have been long on ambiguity without that.

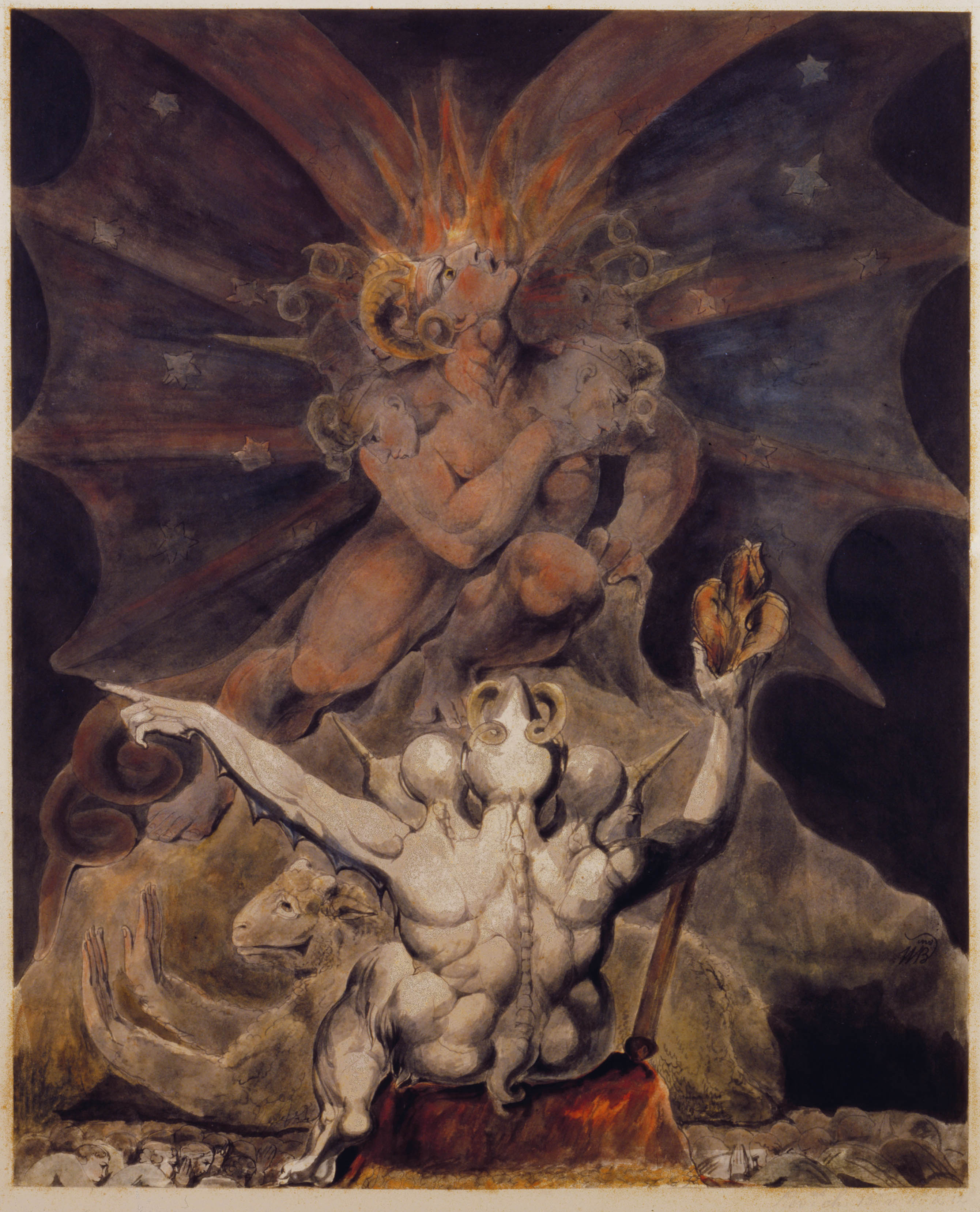

THE NUMBER OF THE BEAST IS 666: Last and in most ways least, it is to “The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea” what “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun” is to “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun”—a drabber and less chilling counterpart. The dragon is in an awkward pose that serves to expose the limitations of Blake’s anatomy, his face flattened in profile in such a way as to lose all animalistic grandeur. It is the one of the paintings to arguably look better when Fuller and company recreate it in “And the Woman Clothed in Sun.” Its one interesting element is the lamb-like figure behind the Beast from the Sea, a point of contrast and dissonance that enlivens the whole.

THE NUMBER OF THE BEAST IS 666: Last and in most ways least, it is to “The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea” what “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun” is to “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun”—a drabber and less chilling counterpart. The dragon is in an awkward pose that serves to expose the limitations of Blake’s anatomy, his face flattened in profile in such a way as to lose all animalistic grandeur. It is the one of the paintings to arguably look better when Fuller and company recreate it in “And the Woman Clothed in Sun.” Its one interesting element is the lamb-like figure behind the Beast from the Sea, a point of contrast and dissonance that enlivens the whole. We continue to count down towards the TARDIS Eruditorum relaunch on March 19th with revised versions of some old blog posts on Sherlock. Proverbs of Hell will run its final two installments on Tuesday and Thursday this week.

We continue to count down towards the TARDIS Eruditorum relaunch on March 19th with revised versions of some old blog posts on Sherlock. Proverbs of Hell will run its final two installments on Tuesday and Thursday this week. Part 1 can be found

Part 1 can be found  It’s January 1st, 2014. Pharrell Williams’s “Happy” has unseated Sam Bailey at number one, while Eminem and Rihanna, Lily Allen, Ellie Goulding, Katy Perry, and One Direction also chart. In the news, since Matt Smith got old and died it’s been exceedingly quiet. Obama signed a budget deal, marijuana was legalized in Colorado, incandescent light bulbs became illegal to sell in the United States, and Latvia adopted the Euro. While on television, Sherlock informed the audience that it was going to lie to them, and then went on to do just that. It had, in the tradition of fair lies, given ample warning. “It’s a trick. Just a magic trick.” And so, of course, it was. Indeed, The Empty Hearse is in effect a ninety minute exercise in arguing that the question of how Sherlock survived The Reichenbach Fall is irrelevant, or at least largely uninteresting.

It’s January 1st, 2014. Pharrell Williams’s “Happy” has unseated Sam Bailey at number one, while Eminem and Rihanna, Lily Allen, Ellie Goulding, Katy Perry, and One Direction also chart. In the news, since Matt Smith got old and died it’s been exceedingly quiet. Obama signed a budget deal, marijuana was legalized in Colorado, incandescent light bulbs became illegal to sell in the United States, and Latvia adopted the Euro. While on television, Sherlock informed the audience that it was going to lie to them, and then went on to do just that. It had, in the tradition of fair lies, given ample warning. “It’s a trick. Just a magic trick.” And so, of course, it was. Indeed, The Empty Hearse is in effect a ninety minute exercise in arguing that the question of how Sherlock survived The Reichenbach Fall is irrelevant, or at least largely uninteresting. Yes, it’s the long-awaited (by a tiny number of people) return of the Shabcast.

Yes, it’s the long-awaited (by a tiny number of people) return of the Shabcast.