By ‘Eck, Hayek!

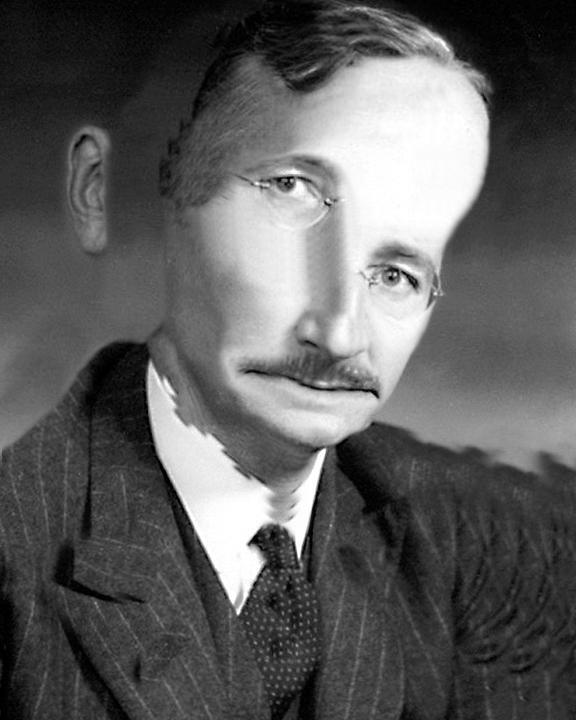

The early Austrian School was actually subject to a split. It stemmed from the first wave of the followers of its founder Carl Menger. Mengerians Friedrich von Wieser and Eugen von Philippovich were both a bit like Fabian socialists in their outlooks. Wieser, for instance, seems to have believed that marginal utility (the radically subjective basis of modern mainstream economics) provided a theoretical foundation for progressive taxation. But Wieser’s brother-in-law and fellow teacher, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, was of the classical liberal tradition. Böhm-Bawerk was a strident anti-Marxist who developed many of his own theories – which became foundational to the subsequent Austrian School – in the course of his criticisms of Marx. Böhm-Bawerk is still routinely credited by some with having demolished Marx… which he accomplished by systematically misreading, misunderstanding, and misrepresenting him.

The early Austrian School was actually subject to a split. It stemmed from the first wave of the followers of its founder Carl Menger. Mengerians Friedrich von Wieser and Eugen von Philippovich were both a bit like Fabian socialists in their outlooks. Wieser, for instance, seems to have believed that marginal utility (the radically subjective basis of modern mainstream economics) provided a theoretical foundation for progressive taxation. But Wieser’s brother-in-law and fellow teacher, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, was of the classical liberal tradition. Böhm-Bawerk was a strident anti-Marxist who developed many of his own theories – which became foundational to the subsequent Austrian School – in the course of his criticisms of Marx. Böhm-Bawerk is still routinely credited by some with having demolished Marx… which he accomplished by systematically misreading, misunderstanding, and misrepresenting him.

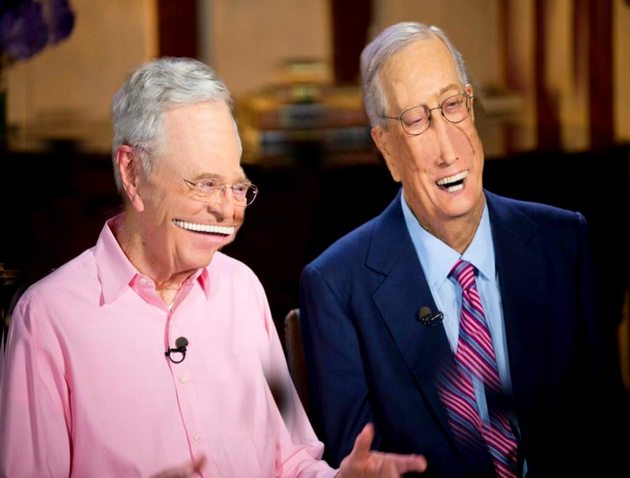

The split was transmitted. Böhm-Bawerk was Mises’ teacher, and Mises became fanatical in his rejection of state intervention (except when he wasn’t… it’s complicated). Wieser was Hayek’s teacher, and Hayek is still thought by some hardliners to have been almost a socialist owing to his ability to countenance some welfare measures. Hayek also believed a state was necessary… which makes him a cuck by anarcho-capitalist standards. In Ancaptopia, law and order would be seen to by private security firms. The principle task of ‘law and order’ (as capitalism sees it) being the protection of private property, we’d actually be talking about capitalists with private armies. Which… would be great, obviously.

Initially, Hayek leaned in Wieser’s direction, apparently having one of those quintessential left-wing ‘phases’ in youth that inoculates a certain kind of person for life. (You could say the same about the Austrian School as a whole.)

Hayek then became Mises’ employee and protege, and drifted in the direction of Mises ideas, though he claimed he was never completely won over… which can be seen in his rejection of outright praxeology in favour of Popperian empiricism.

Despite being the prime mover behind early neoliberalism, an ideology devoted to attacking social provision, Hayek never completely abjured every possible form of welfare state. In the third volume of Law, Legislation, and Liberty (published in 1979, a long time after his youthful socialist phase) he makes noises about how Universal Basic Income may even be “a necessary part of the Great Society”. (Indeed, Milton Friedman the monetarist also refused to completely rule out some form of provision for the poor. His ‘Negative Income Tax’ proposals are testament to that.)

But then neoliberalism does not, and will not, eliminate all social provision. I think the neoliberals – the saner ones anyway – understand that you can’t actually have functioning modern capitalism unless there is a state that takes on some of the burden of making sure capital has a surviving workforce. The insistence upon eliminating welfare is a tactical ideological aim more than an actual plan. And many thoroughgoing neoliberals will defend social provision of some kind, as indeed did Hayek and Friedman, etc.

As has been noted by many left-commentators, neoliberalism is not actually anti-state except with reference to the state’s capacity to exercise any semblance of public control over capital flow.…

The Dark Knight Rises

The Dark Knight Rises As some of you will be aware, especially those of you who’ve been following my whining about it on Twitter, I’ve recently been finishing up something I’ve been writing about the Austrian School of economics (y’know, Mises, Hayek, Rothbard, right-libertarianism, etc). It’s my side of a collaboration with Phil for his next book. It’s taken a long time (my fault) but I just finished. One of the reasons it took so long was because I kept falling down rabbit holes, so to speak. The good thing about that is that it has left me with excess material I can write up. And here’s the first bit.

As some of you will be aware, especially those of you who’ve been following my whining about it on Twitter, I’ve recently been finishing up something I’ve been writing about the Austrian School of economics (y’know, Mises, Hayek, Rothbard, right-libertarianism, etc). It’s my side of a collaboration with Phil for his next book. It’s taken a long time (my fault) but I just finished. One of the reasons it took so long was because I kept falling down rabbit holes, so to speak. The good thing about that is that it has left me with excess material I can write up. And here’s the first bit.  It seems silly to start anywhere besides the Joker. We’ll set aside the cynical but not entirely unfounded question of whether the performance would be as celebrated as it is were it not for Heath Ledger’s untimely death and the ghoulish speculation (since refuted) that the psychological intensity of the role was a cause. Sure, it’s tough to imagine a Batman film winning an acting Oscar under less tragic circumstances, but that’s in no way what’s interesting here. What’s interesting is that Ledger and Nolan took the most oversignified character in Batman mythos (and yes, of course I’m including the big rodent himself) and offered a game-changing take on him. The hunched, disheveled figure with a Glasgow smile is a new angle, skewing the Joker towards a materialism that is generally precisely what’s discarded in other efforts to make him more grandiosely crazy. Ledger and Nolan offered a new way for the Joker to be.

It seems silly to start anywhere besides the Joker. We’ll set aside the cynical but not entirely unfounded question of whether the performance would be as celebrated as it is were it not for Heath Ledger’s untimely death and the ghoulish speculation (since refuted) that the psychological intensity of the role was a cause. Sure, it’s tough to imagine a Batman film winning an acting Oscar under less tragic circumstances, but that’s in no way what’s interesting here. What’s interesting is that Ledger and Nolan took the most oversignified character in Batman mythos (and yes, of course I’m including the big rodent himself) and offered a game-changing take on him. The hunched, disheveled figure with a Glasgow smile is a new angle, skewing the Joker towards a materialism that is generally precisely what’s discarded in other efforts to make him more grandiosely crazy. Ledger and Nolan offered a new way for the Joker to be. With a title like The Punishment of Luxury coming out into a geopolitical climate like this one, and knowing OMD’s past dalliances with progressive social and cultural criticism, I can’t help but read great things into this new album from the get-go. It’s been out since September so literally everyone in the world has had a chance to listen to it before me, but my copy (yes I still buy CDs, certainly when it comes to stuff like this, shut up) just arrived a few weeks ago as of this writing due, happily, to the fact it was out of stock on release date, which implies it’s selling really well! I’m not going to attempt a “proper” review or anything like that: I’m not a musicologist, music historian or music critic (Andrew Hickey and Phil are both much, much better at that sort of thing than I could ever hope to be) so I’m going to stop pretending I am and just give my thoughts on what this album says to me and how it makes me feel on a gut personal and emotional level.

With a title like The Punishment of Luxury coming out into a geopolitical climate like this one, and knowing OMD’s past dalliances with progressive social and cultural criticism, I can’t help but read great things into this new album from the get-go. It’s been out since September so literally everyone in the world has had a chance to listen to it before me, but my copy (yes I still buy CDs, certainly when it comes to stuff like this, shut up) just arrived a few weeks ago as of this writing due, happily, to the fact it was out of stock on release date, which implies it’s selling really well! I’m not going to attempt a “proper” review or anything like that: I’m not a musicologist, music historian or music critic (Andrew Hickey and Phil are both much, much better at that sort of thing than I could ever hope to be) so I’m going to stop pretending I am and just give my thoughts on what this album says to me and how it makes me feel on a gut personal and emotional level.