Eruditorum Presscast: The Pyramid at the End of the World

The podcast for The Pyramid at the End of the World is up for your listening enjoyment. You can download it here.…

The podcast for The Pyramid at the End of the World is up for your listening enjoyment. You can download it here.…

The Mestral is stunned, but not for long.

The Mestral is stunned, but not for long.

Rav implores that he only wants her “safe” (which the Mestral quite aptly reads as “tame”). He claims he’s trying to protect her from the factions trying to assassinate and usurp her. But the Mestral sees right though his ploy-He’s working for one of the other factions, and they’re trying to use her own feelings of love and loyalty to cloud her judgment. And she can play the same game: Having directly threatened her, Rav must be arrested and tried, and the only way for him to escape sentence is to kill her. Which she knows he won’t do, because he loves her.

The Mestral covertly opens an audio channel to the Enterprise, and, by cleverly rephrasing an exposition recap into a challenge (“You used that phaser on Venant, Rav, but you won’t use it on me…So you may as well put it away”), she manipulates Rav into revealing his plan to the Enterprise crew. He knows he can’t shoot her and that she won’t back down, so he and his co-conspirators are planning to kidnap her and bring her back to Eldalis where she’ll be “mentally reprogrammed”, brainwashed into becoming more placid and obedient. Captain Picard is appalled, and immediately has Doctor Crusher, Commander Riker, Data and a security team beam over to the Mestral’s ship to intervene. The transporter chiefs warn the solar flares will cause problems, but they’ll do their best. On the yacht, the Mestral declare she’ll die before she becomes “a cherished puppet with a lover’s hands on the strings”. Another struggle ensues and it looks like this time Rav might get the upper hand, but then Commander Riker beams in and takes him into custody.

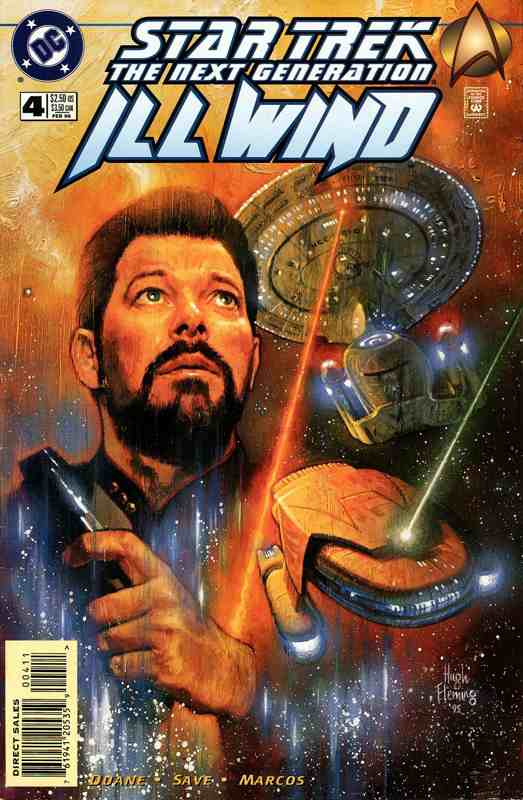

The problem now is that the solar flare activity has picked up enough it’s impossible to transport back to the Enterprise, so Will and Data are going to have to sail out themselves. Rav offers to help pilot, but, as Will pointedly snaps “I’m a little short on blind trust at the moment. You sit down where I can see you and stay away from the controls”. Data begins to start the emergency backup engine, but Rav says it’s broken. Will muses “How would you know? Unless, of course you had something to do with it”. Will and Data are going to have to do it the old fashioned way, but thankfully Captain Picard is an expert and offers to talk them through what they have to do. Just then, the Mestral’s support tender arrives, but Worf observes it’s curiously well-armed. He, Captain Picard and Commander Riker all come to the same conclusion at once: This is the getaway vehicle for Rav and his co-conspirators, timed to arrive just when the star would be flaring such that transporters would be inoperable. Knowing the yachts are so small and fragile they couldn’t survive even one hit, Captain Picard puts the Enterprise between the tender and the sailboat and prepares for battle, while Commander Riker does his best to get out of the way.…

BUFFET FROID: Literally “cold buffet,” referring specifically to a charcuterie platter of thin-sliced meats. In this context, a joke about Georgia Madden’s shredding skin.

BUFFET FROID: Literally “cold buffet,” referring specifically to a charcuterie platter of thin-sliced meats. In this context, a joke about Georgia Madden’s shredding skin.

It goes without saying that there is a strange unreality here, but this is presented very differently from how Hannibal usually proceeds. It’s never before had to conjure a disposable POV character just to kill her off a few minutes later. Part of this is the peculiarities of Georgia Madden – she’s unsuitable to be a POV character herself, and there’s only one other choice. But a more basic reason is that this is the opening of a horror movie, with Madden being positioned as something that comes at the show from an odd angle She doesn’t quite belong in this series. Unlike with “Œuf,” a previous case of a killer of the week who’s not quite right for Hannibal, this is something the show is at least conscious of this time.

Timeline of events.

I leave you to your own conclusions.

HANNIBAL: We both know the unreality of taking a life, of people who die when we have no other choice. We know in those moments they’re not flesh, but light and air and color.

WILL GRAHAM: Isn’t that what it is to be alive.

Hannibal’s line here is a characteristically interesting blend of deceit and honesty. His account of people becoming “light and air and color” is quite untethered to the handful of instances of actual necessity in which Hannibal has killed someone, and for that matter an unusual description for Hannibal, whose victims are pointedly never “not flesh.” Some explanation is offered by the source, which is unsurprisingly the Thomas Harris novels, where a similar account is given by Francis Dolarhyde, who describes killing this way while projecting this assessment onto Hannibal. Its repurposing into a half life with which Hannibal ensnares Will into mutual aesthetic appreciation is clever.

The misdrawn clocks are one of the defining images of the latter part of the first season – an immediately arresting image that communicates wrongness and sinister intent without actually having anything overtly horrifying about them. In this regard they are much like the trypophobic food designs, the cluster of numbers and vast expanse of white space both communicating a sense that this is not right even beyond the contextual horror of Hannibal’s manipulations, which are suddenly revealed to be far more advanced than the audience had realized. Note, of course, the consistent feature of Will’s breakdown: the decoherence of time.

…JACK CRAWFORD: You contaminated the crime scene.

WILL GRAHAM: I thought I was responsible for it.

JACK CRAWFORD: You thought you killed that woman?

WILL GRAHAM: Sometimes with what I do —

JACK CRAWFORD: What you do is take whatever evidence there is and extrapolate. You reconstruct the thinking of a killer, not think you are a killer.

A recurrent and to my mind fascinating theme of Peter Harness’s Doctor Who work has been its distinct hostility to democracy. Kill the Moon hinges on the flagrant disregard of the expressed wishes of humanity, while the Zygon two-parter ultimately endorses the existence of unelected guardians who lie to people in order to keep them under control. I should stress, if it’s not obvious, that my fondness for this is not straightforwardly a quasi-neoreactionary rejection of democracy or endorsement of dictatorship – rather it is specifically the extent to which the episodes themselves seem conflicted on this. It’s a bit of grit that complicates the show’s default ethos of liberal centrism – something that extends naturally out of its embrace of rebelliousness and dissent, but that the show usually avoids having to look at head-on.

So it’s not especially a surprise that Harness, writing in the heat of 2016, turns in a script that is more explicitly about the terrible decisions that humanity makes than ever before. This time there is no undemocratic savior to be had. Indeed, there’s not a savior of any kind – the bad decision is taken and the bad guys win. The Doctor’s scheme to stop them is basically for naught. For the most part it’s an even bigger defeat for the Doctor than Extremis was, and is certainly the most bluntly pessimistic thing Harness has written for the show.

For the most part, this works. Certainly it’s something I’m glad the series did. But as with Oxygen, there’s a grimness to it that keeps it from ever quite being fun. There are moments of humor, to be sure, and it’s difficult to seriously suggest that an episode marching towards an ending like this while also situating itself as the middle part of a trilogy that starts with Extremis would be very frock. But there’s a nagging frustration – a sense that “geopolitical thriller” is not the Doctor Who subgenre that Harness was best pigeonholed into. I mean, I can see why it happened – many of the best bits of both Kill the Moon and the Zygon story were the overtly political bits. But what made those stories really sing was the juxtaposition between the snarling politics and the baroque ridiculousness. Here, lacking a fundamental part of the equation, Harness is… well, still fantastic, to be clear, but not at the ecstatic heights of the last two seasons. Which, to be fair, you can thus far say about Series 10, which is starting to shape up a lot like the back half of Series 7: no disasters, but no stone cold classics either.

And of course, we should be clear: this is an absolutely bonkers political thriller. Which is to say, it’s still clearly Doctor Who, and not just because of touches like the corpse monks or the “strands of history” plastic tubing. The Doctor Whoness of it comes as much from what isn’t there, like even a vague account of why the Russian, American, and Chinese militaries are in close proximity in a foreign country or where the hell the entire rest of the chain of command is.…

Hello there… bit of a serious Shabcast this time, though there are some laughs along the way.

Hello there… bit of a serious Shabcast this time, though there are some laughs along the way.

(EDIT: I forgot to say that I’m joined by James – who really knows about this stuff – and Daniel – who really knows about this stuff in America.)

This episode was prompted by the ‘Dementia Tax’ story, and became about the crisis in the NHS generally, and also about the horrors of the American system. It was recorded before the ‘Dementia Tax’ story developed (with Theresa May’s humiliating kindasorta u-turn) and also before the attack in Manchester, so it’s a bit of a relic… but even so, these are live issues, and a lot of what we say hasn’t gone out of date. The NHS is still in crisis, and its still the Tories’ fault, but also still tracks back to New Labour. And the American system is still awful, and the few improvements made by Obama may still be about to be destroyed, and we in the UK are still headed in that privatised, profit-driven direction.

I’d appreciate people sharing this about, for propaganda/electioneering purposes. You never know, it might help a bit.

The audio sample at the start is from this video, which I’d also suggest sharing around.

And here are the links (promised in the show) to the information about the 30,000 excess deaths in 2015 owing to NHS underfunding (I was going to link to the study itself but that doesn’t seem to be possible):

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2017-02-analysis-links-excess-deaths-health.html

And I ask a simple question: if its terrorism to set off a bomb in a concert, killing 22 people (and it undoubtedly is), then what do you call knowingly and deliberately underfunding a health service that people depend on for their survival, needlessly causing 30,000 extra deaths? For reasons grounded in political ideology?

On a slightly lighter note, here’s a link to the podcast about Bill O’Reilly’s book that Daniel mentions… unless I cut that bit out, I don’t remember at this point. Good podcast anyway.

*

EDIT: Here’s something Kit wrote, which acts as a companion (an equal one) to this Shabcast:

http://kitpowerwriter.blogspot.co.uk/2017/05/uk-general-election-2-dementia-tax-u.html?spref=tw

…

I’m joined by Jack Graham to talk Extremis. It doesn’t so much go off the rails quickly as never actually manage to find the rails in the first place. You can download that here if you’re so inclined.…

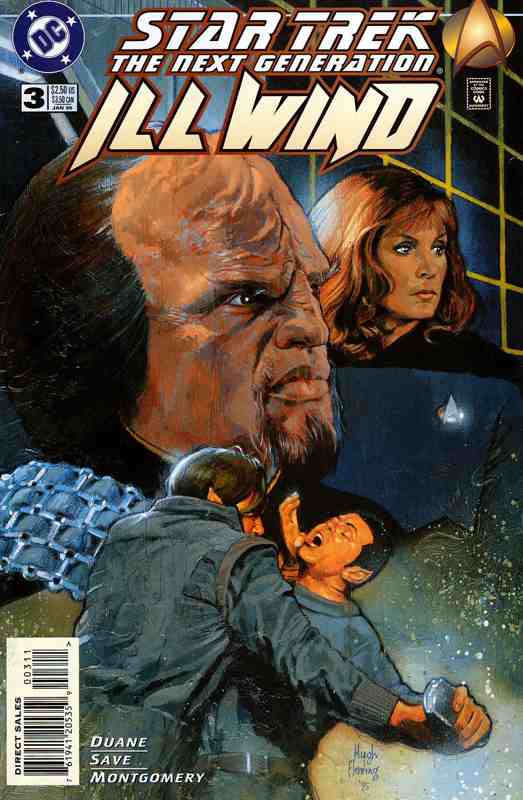

Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship’s internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that’s how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind.

Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship’s internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that’s how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind.

Geordi can pick up thermal signatures from the sensor feed through his VISOR. Although he can’t yet get much on the figure itself, he can tell it’s carrying a plasma bomb, though it hadn’t yet been armed (which explains why the ship’s sensors didn’t immediately detect it as well). Once the figure enters the shuttlebay, Geordi can get more information because the sensors are more sensitive there. That the figure’s internal body temperature of 320K confirms it is most certainly not human: Worf asks “Is 320K bad in human terms?”, to which Doctor Crusher responds “It’s dead in human terms”. Furthermore, Bev can discern that the figure has no heart and no stomach but does have “a selectively absorptive gut”, a “nondiastolic perfusion system” and six kidneys. Unusual and excessive for a humanoid, but not for the Carrighae. In other words, this person is a Carrig disguised, albeit somewhat clunkily, as a humanoid in order to throw suspicion onto one of the other teams.

Such a breach of the ethics agreement as attempting to murder one of the other teams is an automatic disqualification, so Worf, Geordi and Beverly go to see Captain Picard. Surprisingly, Jean-Luc decides to not do anything at all…At least not until the end of the race. His first explanation is to glibly state that the information must be “properly authenticated” and ensured that it goes through all the necessary channels. Of course, this also means that the Carrighae will have to “sweat and strain like all the rest, assuming that they do sweat”. After everything runs its natural course, Captain Picard will then turn the information over to race officials. When Geordi asks what will happen if the Carrighae win, Captain Picard says “All the better. Just imagine their reaction when they discover what their own dirty trick has done to them. Let them go home and file litigations until they’re blue in the face, or whatever color they routinely turn at such times. Starfleet will tell them where to get off, and in short order, too”.

Worf asks if this counts as vengeance or retribution. Jean-Luc insists that it’s justice, but that “sometimes it’s more of a pleasure serving it than others”. Worf tells the Captain that with a bit more work, he’d make a fine Klingon.…

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

One of the show’s most emphatically memorable murder tableaus – probably the only one to give Eldon Stammetz and his mushroom people a run for their money. It also serves, however, as a case study in the schizoid nature of this season. More than anywhere else in the first season, “Trou Nourmand” demonstrates the degree to which these cases of the week are a charade. The totem pole murders are barely a feature of the episode, squared away with almost comical efficiency midway through the fourth act while the plot focuses instead on Will’s psychological collapse and new developments with Abigail.

BRIAN ZELLER: The world’s sickest jigsaw puzzle.

JIMMY PRICE: Where are the corners? My mom always said start a jigsaw with the corners…

BRIAN ZELLER: I guess the heads are the corners?

BEVERLY KATZ: We’ve got too many corners. Seven graves. Way more heads.

In which Zeller, Price, and Katz demonstrate that the aesthetics of murder tableaus are not their strong suit.

WILL GRAHAM: I planned this moment… This monument with precision. Collected all my raw materials in advance. I position the bodies carefully, according each its rightful place. Peace in the pieces disassembled. My latest victim I save for last. I want him to watch me work. I want him to know my design.

This monologue, especially the bit about “according each its rightful place,” evokes one of the less explicit ancestors of Hannibal, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, and particularly the memorable anecdote in which Moore made an error describing the placement of a severed breast within a historical murder tableau, only realizing the error after Campbell had drawn the page and several further. His solution is to have the killer pause several pages later, look at the severed breast, think for a moment, and rearrange it to better fit his strange and awful aesthetic.

WILL GRAHAM: I was on a beach in Grafton, West Virginia… I blinked and then I was waking up in your waiting room. Except I wasn’t asleep.

HANNIBAL: Grafton, West Virginia is three-and a-half hours from here. You lost time.

WILL GRAHAM: Something is wrong with me.

As Crowley would put it, Will’s encephalitis is a disease of editing.

HANNIBAL: I’m your friend, Will. I don’t care about the lives you save. I care about your life. And your life is separating from reality.

WILL GRAHAM: I’ve been sleepwalking. I’m experiencing hallucinations. Maybe I should get a brain scan.

HANNIBAL: Damnit, Will. Stop looking in the wrong corner for an answer to this.

(Will is briefly startled by Hannibal’s passionate concern.)

HANNIBAL: You were at a crime scene when you disassociated. Tell me about it.

This scene requires that we read it in the context of “Fromage” and its resolution and thus assume that Hannibal is motivated by a sincere desire for friendship with Will.…

At its structural root, it’s Moffat doing Doctor Who like it’s Sherlock, which is the sort of thing where when you do it, you know it’s probably time to move on in your career. This, of course, does not mean it’s bad. It’s not even a criticism – more just a reality of Moffat’s set pieces twelve years into his writing for the program. He passed Robert Holmes for most screen minutes of Doctor Who written somewhere around the “sit down and talk” speech in The Zygon Inversion. (Yes, I counted Brain of Morbius for Holmes as well.) His stylistic tics have long since evolved to cliches, blossomed into major themes, and finally twisted into strange self-haunting shadows that echo endlessly off of each imprisoned demon and fractured reality. They become difficult to actually talk about on some level And so approaching them from the standpoint of their dramatic engines becomes productive.

The first thing to note, then, is that Sherlock provides a pretty good narrative shell for Doctor Who to inhabit. The globehopping thriller has always worked for Doctor Who, and the Vatican is a good choice for “who should bring a case to the Doctor.” The double structure whereby we keep cutting back to the Missy story is of course the sort of thing Moffat can do effortlessly, and adds enough complexity to establish the crucial “what kind of story is this going to be” tension. And that is very much what it does. Like Listen and Heaven Sent, this is a story that goes out of its way up front to announce that it’s going to be doing a magic trick. Central to this trick is the middle section, set in a library whose layout is deliberately confusing and unclear – the perfect place for reality to quietly fray and break down. Which brings us to the third act.

It’s here things get a bit interesting, with ideas that drive you mad, people being reincarnated on computers, and AIs trying to escape the boxes they’ve been put in. Why Mr. Moffat, I don’t remember you being one of my Kickstarter backers. More seriously, because I’m sure in reality that Moffat just plucked these ideas out of the same ether I did, this is obviously touching some territory and themes I’ve dealt with before. But it’s generally easy to make too much of this, which I’m sure I’ll get around to doing someday. For now, let’s just point out that while I don’t pretend to be an expert in AI and computers, I’m not the sort of person who suggests that every part of a computer can send an e-mail and then acts as though this is in any way a sensible way to anchor the resolution.

Which is to say that while Moffat is nicking the broad ideas of simulationism, this is not even close to a serious exploration of the concepts. His interest in it extends exactly as far as “it’s another way to do an ‘and now for some metafiction’ twist” and no further.…

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger?

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger?

*

Today, suffocation has a very specific meaning. In America, you can tell upon which side of the divide someone stands by seeing what their t-shirt tells you about their ability – or otherwise – to respirate. The divide in question is one created by a system of oppression that chokes people. It chokes them figuratively, and then has the brazen impudence to choke them literally as well.

One statement of resistance is the simple proclamation “I can’t breathe”, which derives its power from its ability to inhabit both the metaphor and the brute reality.

Part of the peculiar power of the metaphorical referent is that it expresses a feeling of helplessness as part of a demonstration of strength. Weaponised weakness.

‘Oxygen’ flirts with the SF trope of the post-racial future. The people of the future don’t understand why Bill should face prejudice. They don’t see colour. Except that there is the business with the blue man (played by a white actor, of course, because whiteness is perceived as neutrality, blankness, non-ethnicity, vanilla standard humanity, upon which a fictional alien ‘race’ may be projected without confusing things). But this seems like little more than a method by which the episode can not talk about race in a talking-about-race kind of way. After the imperfect but forthright way ‘Thin Ice’ touched on this subject, this is a failing. Apart from anything else, the refusal to depict class as imbricated with any particular hierarchical dynamics of race or gender is an especially glaring omission in an episode which, for once, explicitly concerns itself with class.

But even so, Bill dies in this episode. She isn’t suffocated, but she is deprived of breath. This happens in the context of a story in which the supply and denial of oxygen is the central iteration of hierarchical power in society. And yet she survives at least partly because she submits to the helplessness enforced upon her by an external force of systemic domination – her suit. She embraces negative capability. As resistance. That she has no choice only amplifies this fact rather than nullifying it. Her tactical embracing of her own helplessness is what ultimately leads to her survival.

She is, of course, saved by a white man. But this, while true and unignorable, is structural to Doctor Who… at least until the Doctor ‘does a Romana’ at the end of the series and chooses to regenerate into a copy of Bill.

(Shall we re-litigate this yet again? There is no way in which texts can be purified. There is no method whereby authors can ever entirely ‘win’. The solution to this problem(atic) is dialectical. It involves transforming society, not trying to amend the practice of authoring texts in the culture industries of late capitalism so that they become imperfectly ‘progressive’. Apart from anything else, what does ‘progressive’ mean in a society progressing towards some species of global choking and suffocation?)…