The Pyramid at the End of the World Review

A recurrent and to my mind fascinating theme of Peter Harness’s Doctor Who work has been its distinct hostility to democracy. Kill the Moon hinges on the flagrant disregard of the expressed wishes of humanity, while the Zygon two-parter ultimately endorses the existence of unelected guardians who lie to people in order to keep them under control. I should stress, if it’s not obvious, that my fondness for this is not straightforwardly a quasi-neoreactionary rejection of democracy or endorsement of dictatorship – rather it is specifically the extent to which the episodes themselves seem conflicted on this. It’s a bit of grit that complicates the show’s default ethos of liberal centrism – something that extends naturally out of its embrace of rebelliousness and dissent, but that the show usually avoids having to look at head-on.

So it’s not especially a surprise that Harness, writing in the heat of 2016, turns in a script that is more explicitly about the terrible decisions that humanity makes than ever before. This time there is no undemocratic savior to be had. Indeed, there’s not a savior of any kind – the bad decision is taken and the bad guys win. The Doctor’s scheme to stop them is basically for naught. For the most part it’s an even bigger defeat for the Doctor than Extremis was, and is certainly the most bluntly pessimistic thing Harness has written for the show.

For the most part, this works. Certainly it’s something I’m glad the series did. But as with Oxygen, there’s a grimness to it that keeps it from ever quite being fun. There are moments of humor, to be sure, and it’s difficult to seriously suggest that an episode marching towards an ending like this while also situating itself as the middle part of a trilogy that starts with Extremis would be very frock. But there’s a nagging frustration – a sense that “geopolitical thriller” is not the Doctor Who subgenre that Harness was best pigeonholed into. I mean, I can see why it happened – many of the best bits of both Kill the Moon and the Zygon story were the overtly political bits. But what made those stories really sing was the juxtaposition between the snarling politics and the baroque ridiculousness. Here, lacking a fundamental part of the equation, Harness is… well, still fantastic, to be clear, but not at the ecstatic heights of the last two seasons. Which, to be fair, you can thus far say about Series 10, which is starting to shape up a lot like the back half of Series 7: no disasters, but no stone cold classics either.

And of course, we should be clear: this is an absolutely bonkers political thriller. Which is to say, it’s still clearly Doctor Who, and not just because of touches like the corpse monks or the “strands of history” plastic tubing. The Doctor Whoness of it comes as much from what isn’t there, like even a vague account of why the Russian, American, and Chinese militaries are in close proximity in a foreign country or where the hell the entire rest of the chain of command is.…

Hello there… bit of a serious Shabcast this time, though there are some laughs along the way.

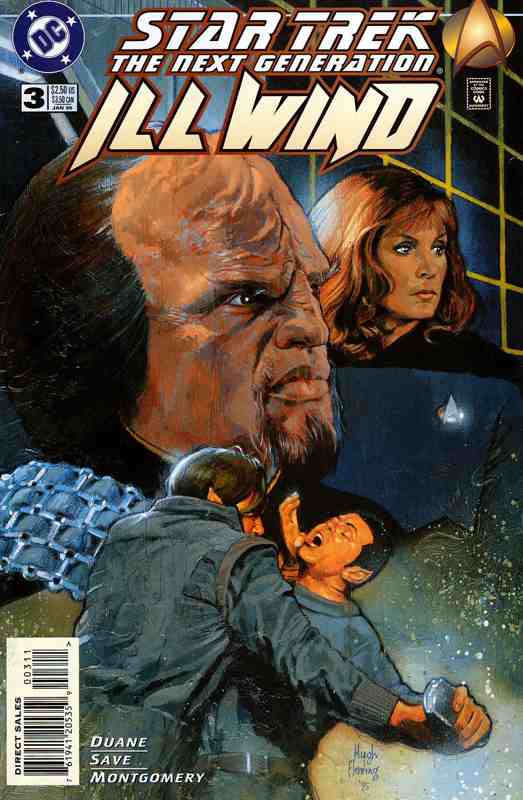

Hello there… bit of a serious Shabcast this time, though there are some laughs along the way.  Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship’s internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that’s how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind.

Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship’s internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that’s how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind. TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger?

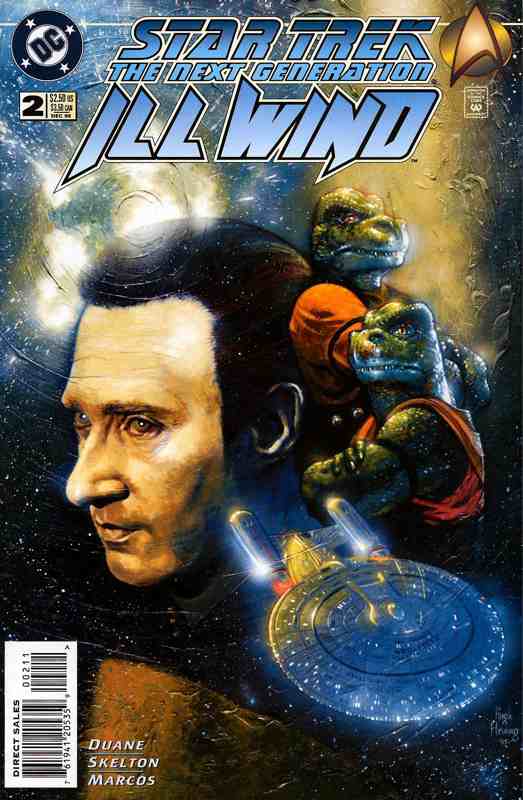

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger? The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It’s a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he’d rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they’re without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary…She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it’s still early yet.

The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It’s a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he’d rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they’re without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary…She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it’s still early yet. Phil was nice enough to cite me in the most recent of his (wonderful) ‘Proverbs of Hell’ series. I just thought I’d be cheeky and repost a little reheated morsel of the stuff of mine that he referred to… because I think it’s quite interesting.

Phil was nice enough to cite me in the most recent of his (wonderful) ‘Proverbs of Hell’ series. I just thought I’d be cheeky and repost a little reheated morsel of the stuff of mine that he referred to… because I think it’s quite interesting.