The Comprehensive History of Injustice

A guest post by Seth Aaron Hershman.

A guest post by Seth Aaron Hershman.

…the entire world might be poisoned. This, however, seemed unlikely, as the world, no matter how monstrously it may be threatened, has never been known to succumb entirely.

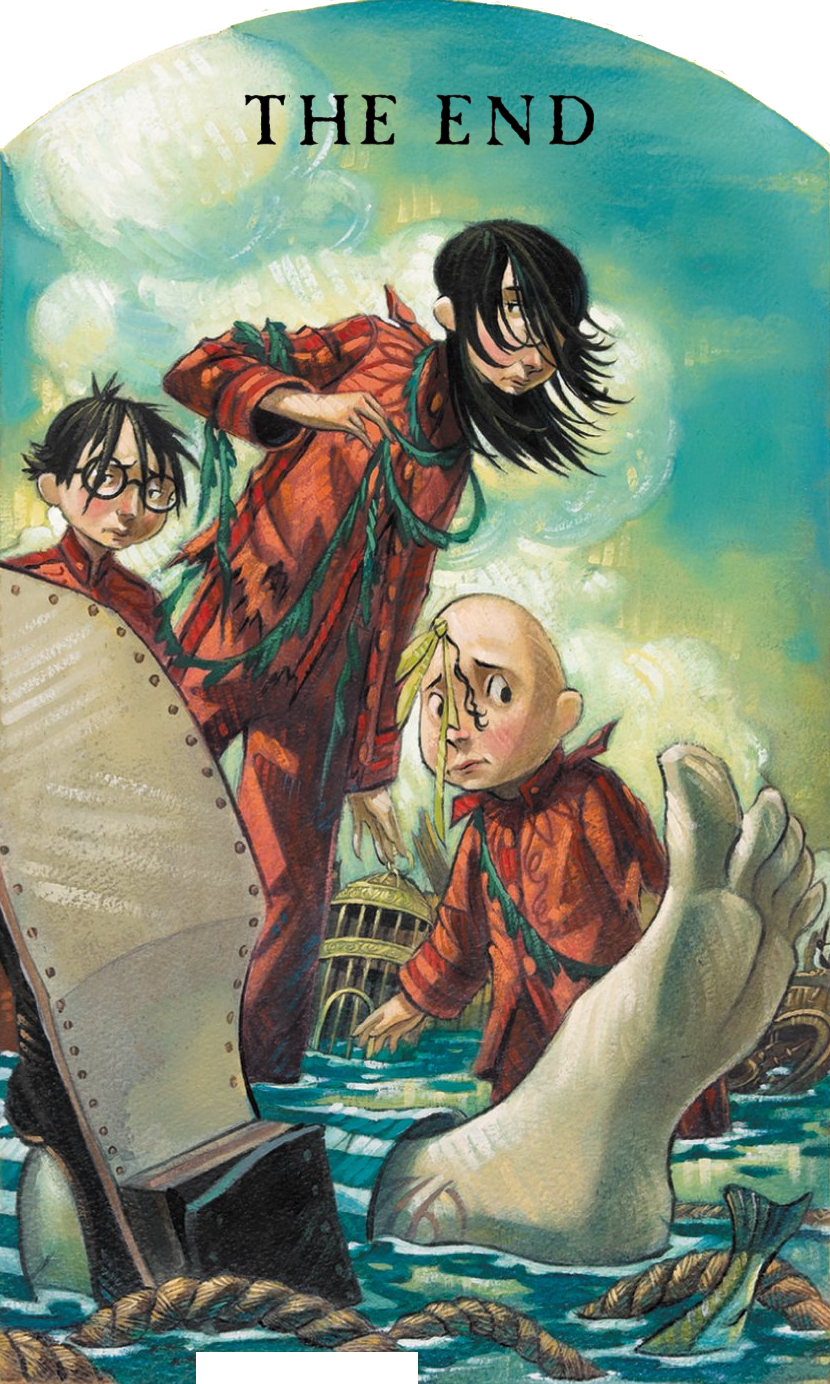

A Series of Unfortunate Events is a book series, and currently a Netflix show, about three orphans, Violet, Klaus, and Sunny Baudelaire, who are chased from place to place by a man named Count Olaf who manipulates (and if necessary knocks off) anyone who might try to take them in so that he can have them–and their inheritance/trust fund–for himself.

Count Olaf is a rich man looking to get richer, who relies on transparent lies and cheap theatrics to get his way, casually uses and discards people, has a roughly third-grade literacy and vocabulary level, and works in entertainment.

It’d be easy to go that route, wouldn’t it?

The issue of timeliness is a difficult one for A Series of Unfortunate Events, a franchise which actively avoids setting itself in a specific era in a way that should be familiar to fans of, say, Archer or Batman: The Animated Series. Because the series goes out of its way not to take place in any particular time, it’s difficult to pin whether the obvious allegory is an act of authorial intent or merely a fortunate coincidence. (One could argue that the fact that these books were written a decade ago makes it a forgone conclusion, but it’s not like our president was anonymous in at the turn of the century.)

In fact, it’s difficult to pin anything. Which is perhaps part of the point–anchored to no time, the series is able to make a broader point about how all times and all eras are susceptible to the transparent lies and cheap theatrics of rich men looking to get richer.

The rich men themselves are not really the point of the series–after all, most of the series’ characters are comfortably well off, and our leads are victimized specifically because Olaf wants at their sizable inheritance. In fact money itself seems to be a little besides the point. The bigger problem is self-absorption, and the inherent flaws in systems built out of self-interest.

The reason Olaf’s schemes always succeed until the last moment is that self-possession is a character flaw on the part of all who take the Baudelaire orphans in. Their uncle Monty knows well enough to suspect “Stephano” but gets hung up on the idea that his new assistant is after his scientific discoveries rather than his newly aquired children. Their aunt Josephine is ruled by her intense phobias and too obsessed with her tragic past to suspect someone who’s obviously manufactured a similar one for the sake of sympathy. And Mr. Poe, the man in charge of the Baudelaire estate, is constantly talking about how important it is that he get back to his other business matters before he has the chance to do even the most basic checking-up on whatever circumstances he’s dumped the children in this time.…

wandering in subterranean catacombs forbidden to the public

wandering in subterranean catacombs forbidden to the public This is the final part of ‘Faeces on Trump’… which now seems a peculiarly poor title for this series… all the worse for being so nearly right. Still, I daresay I shall have more to say about Trump and related issues in the years to come (if I’m spared). But this first line of thought draws to a close. This post is, as a result, a kind of ‘summing up’. (God, I sound pompous, don’t I?) Further thoughts, or lines of thought, will have to stand alone from now on – and so I’ll be able to retitle for more relevance when I arrogantly shit them all over the internet, as if my opinion matters. But anyway, this is the last squirt of diarrhea from the bellyache that Trump’s victory gave me. Further dyspepsia will doubtless cause more and different effluvia to rain down upon you, because clearly I can’t help myself. (And you’re not even paying me!) Watch this space, you poor doomed motherfuckers.

This is the final part of ‘Faeces on Trump’… which now seems a peculiarly poor title for this series… all the worse for being so nearly right. Still, I daresay I shall have more to say about Trump and related issues in the years to come (if I’m spared). But this first line of thought draws to a close. This post is, as a result, a kind of ‘summing up’. (God, I sound pompous, don’t I?) Further thoughts, or lines of thought, will have to stand alone from now on – and so I’ll be able to retitle for more relevance when I arrogantly shit them all over the internet, as if my opinion matters. But anyway, this is the last squirt of diarrhea from the bellyache that Trump’s victory gave me. Further dyspepsia will doubtless cause more and different effluvia to rain down upon you, because clearly I can’t help myself. (And you’re not even paying me!) Watch this space, you poor doomed motherfuckers. Patriarchy is built on epic time. Learned male history requires exhaustive documentation of political kingdoms and dynastic successions. The Chosen Warrior-Hero God-King must come of age, become anointed, take a throne and lead his people to victory in battle before retiring and passing his crown on to the next generation. Rise, fall and rise. In our language, we call this canon, and the canon of the aristocratic literate patriarchy stands in stark contrast to the cyclical deep time of the feminine and feminine understanding. This is, in fact, the true first war in the world, and its battle scars have played out across the visage of our ideaspace since the start of all time.

Patriarchy is built on epic time. Learned male history requires exhaustive documentation of political kingdoms and dynastic successions. The Chosen Warrior-Hero God-King must come of age, become anointed, take a throne and lead his people to victory in battle before retiring and passing his crown on to the next generation. Rise, fall and rise. In our language, we call this canon, and the canon of the aristocratic literate patriarchy stands in stark contrast to the cyclical deep time of the feminine and feminine understanding. This is, in fact, the true first war in the world, and its battle scars have played out across the visage of our ideaspace since the start of all time. Wandering in open country is naturally depressing

Wandering in open country is naturally depressing Dedicated, with all awareness of the impudence and absurdity of doing so, but also with sincere love and respect, to the memory of John Berger.

Dedicated, with all awareness of the impudence and absurdity of doing so, but also with sincere love and respect, to the memory of John Berger.