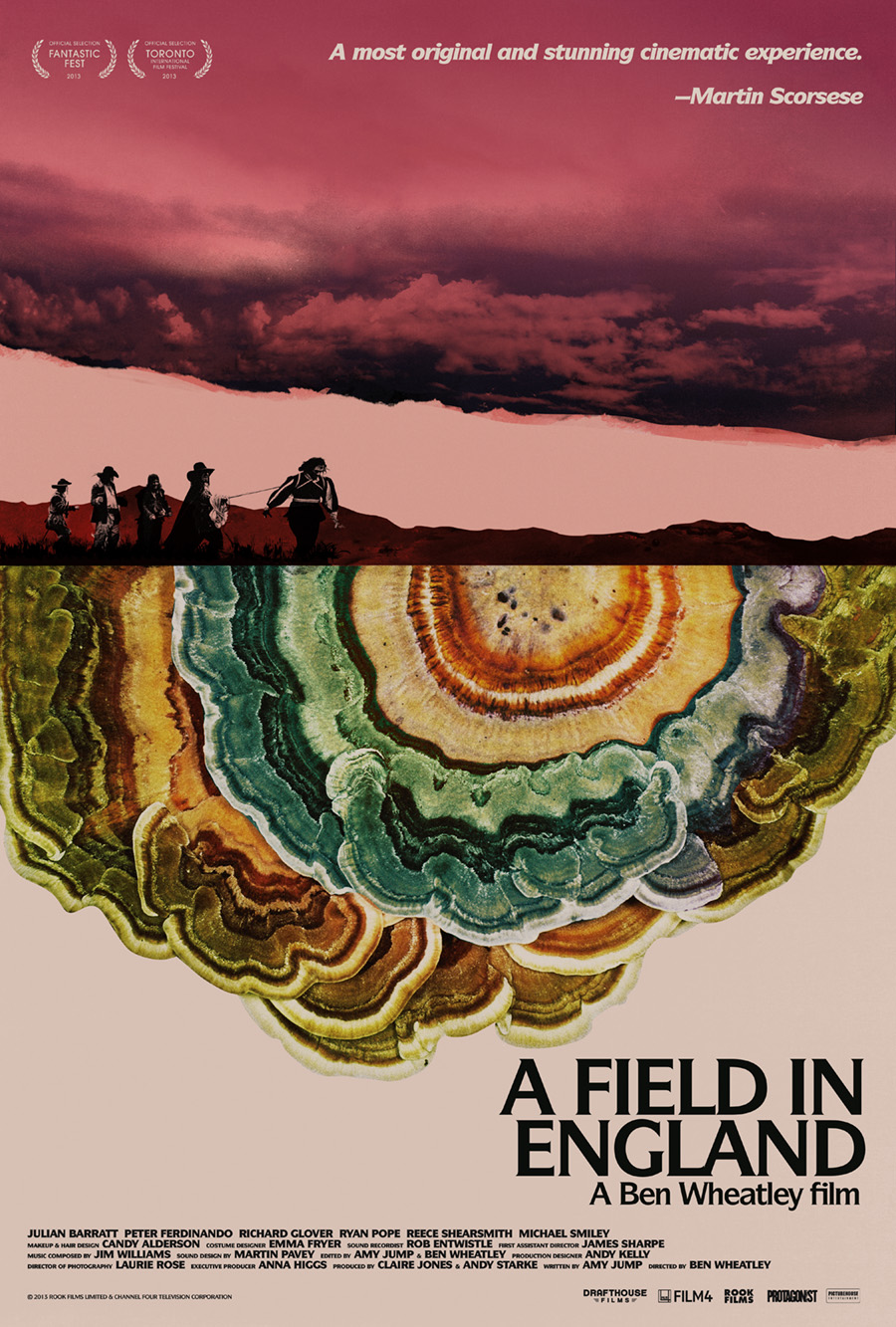

Build High for Happiness 6: A Field in England (2013)

Wandering in open country is naturally depressing

Wandering in open country is naturally depressing

A Field in England is a precise antipode to High-Rise, a fact acknowledged by Ben Wheatley, who has spoken about the way in which he is inclined to make one project a reaction against the previous one. But the thing about the alchemical union of opposites is that it works largely because of the similarities. Just as “up” and “down” presuppose movement in three-dimensional space and “left” and “right” presuppose neoliberal democracy, High-Rise and A Field in England presuppose a director doing sci-fi/fantasy inflected period pieces rooted in the psychogeographies of English spaces. In some understandings of conceptual space this is how the hypercubic prison works – through the systematic construction of axes bounded by opposites that, when multiplied sufficiently, create a territory that is at once infinite and contained.

This is in essence the problem that faces Whitehead, who winds his way through a recurrent series of at best gradual enlightenments in pursuit of no obvious goal or trajectory for escape. More to the point, his problem is heavily location-dependent, in both spatial and temporal senses. Spatially he is confined to the eponymous field, a setting we’ll unpick momentarily. Temporally, however, he is bound by the English Civil War. It has often been suggested that this event serves as the origin for the contemporary socio-political system, an argument that’s generally based on reading it as a transition between the established aristocracy of Charles I and the revolutionary fervor of the Puritans. This is an oversimplification in countless regards, not least that it misunderstands history as something with an origin as opposed to as a series of debts inherited and bloodily paid off from era to era. The English Civil War is certainly an instance of this, but it’s ridiculous to suggest that what emerged from it is somehow a sui generis origin as opposed to an if not inevitable at least entirely sensible consequence of what came before.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that Whitehead straddles both sides of this transition, or perhaps more accurately, is stepping over the divide himself. His status as an alchemist clearly situates him in the world that is receding. But the arc of his slow ascension is clearly towards a measure of individual liberty and away from the crass and domineering tyranny offered by O’Neil, which affiliates him more with the Puritans. Like us, he’s trapped on the inexorable slide down history’s birth canal – just from a substantively different angle. Or, if you prefer something in keeping with ascension, headed up the chimney, an identity gone up in smoke.

This leaves location: a field in England. Central to this is its raw genericness. There are a lot of fields in England, another consequence of the way in which the whole of the island is the product of human development and intervention. And there were a lot of them in the Civil War; Alan Moore is fond of claiming one near Northampton as the place where it was won, although that was merely the first of three, and dialogue about Pembroke places this one during the second, a few years later.…

Dedicated, with all awareness of the impudence and absurdity of doing so, but also with sincere love and respect, to the memory of John Berger.

Dedicated, with all awareness of the impudence and absurdity of doing so, but also with sincere love and respect, to the memory of John Berger. I don’t think any of the characters on the cover here actually appear in the issue. Certainly not that lady Romulan Commander: Davoros is male, I think.

I don’t think any of the characters on the cover here actually appear in the issue. Certainly not that lady Romulan Commander: Davoros is male, I think. a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration

a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration Just in time to see out the year, it’s the debut of Yet Another Eruditorum Press Podcast! A show I have tentatively decided to entitle Spirit Tracks, because reasons. I’m really excited to be able to share this new series with all of you: It’s a project I’ve been working on for a great deal of time and it’s gone through a number of different conceptual phases and incarnations. In its current form, I expect to be mainly doing commentary tracks on assorted bits of visual media, but I also hope to build a stable of regular guests and topics as the show evolves. I’ve already got a great series of co-hosts lined up for the first block of episodes, and I can’t wait to introduce you to each of them.

Just in time to see out the year, it’s the debut of Yet Another Eruditorum Press Podcast! A show I have tentatively decided to entitle Spirit Tracks, because reasons. I’m really excited to be able to share this new series with all of you: It’s a project I’ve been working on for a great deal of time and it’s gone through a number of different conceptual phases and incarnations. In its current form, I expect to be mainly doing commentary tracks on assorted bits of visual media, but I also hope to build a stable of regular guests and topics as the show evolves. I’ve already got a great series of co-hosts lined up for the first block of episodes, and I can’t wait to introduce you to each of them. So, farewell 2016. But don’t worry. Plenty of nasty shit is going to happen next year too.

So, farewell 2016. But don’t worry. Plenty of nasty shit is going to happen next year too.