An Increasingly Inaccurately Named Trilogy: Episode I – The Phantom Menace

Fittingly, this project exists for three basic reasons. First, having subjected everybody to eight parts of Build High for Happiness, it felt like it was time for a nice populist project. Second, I was seized by a desire to watch all seven Star Wars movies and figured “why waste the research.” But third, I was struck by the fact that, as I put it on Twitter a while ago, the bulk of criticism of the Star Wars prequel trilogy is worse at being criticism than the prequels are at being movies. The most common type is of course the brutal and sneering takedown, an approach that usually ends up committing so totally to its brutality that it gives up on making actually interesting points in favor of preening snark. The second is the counter-tendency of contrarian apologias, which are generally better (I’m partial to Rian Johnson’s “the prequels are a 7 hour long kids movie about how fear of loss turns good people into fascists. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯”) but still suffer from wanting to be in conversation with the Red Letter Media shit, and also from the fact that they’re taking a provocative position at the expense of actually being right, which is fine, but you should be able to do both. Particularly lacking, it struck me, are approaches that actually attempt to look at the whole of Star Wars as it presents itself: a story beginning with The Phantom Menace and continuing through to The Force Awakens and, eventually, beyond. A few exceptions exist – perhaps most notably Mike Klimo’s epic “Ring Theory” series, but for all its admirable attention to detail there’s a maddening sterility to the whole affair, reducing the series to an intellectual exercise.

Fittingly, this project exists for three basic reasons. First, having subjected everybody to eight parts of Build High for Happiness, it felt like it was time for a nice populist project. Second, I was seized by a desire to watch all seven Star Wars movies and figured “why waste the research.” But third, I was struck by the fact that, as I put it on Twitter a while ago, the bulk of criticism of the Star Wars prequel trilogy is worse at being criticism than the prequels are at being movies. The most common type is of course the brutal and sneering takedown, an approach that usually ends up committing so totally to its brutality that it gives up on making actually interesting points in favor of preening snark. The second is the counter-tendency of contrarian apologias, which are generally better (I’m partial to Rian Johnson’s “the prequels are a 7 hour long kids movie about how fear of loss turns good people into fascists. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯”) but still suffer from wanting to be in conversation with the Red Letter Media shit, and also from the fact that they’re taking a provocative position at the expense of actually being right, which is fine, but you should be able to do both. Particularly lacking, it struck me, are approaches that actually attempt to look at the whole of Star Wars as it presents itself: a story beginning with The Phantom Menace and continuing through to The Force Awakens and, eventually, beyond. A few exceptions exist – perhaps most notably Mike Klimo’s epic “Ring Theory” series, but for all its admirable attention to detail there’s a maddening sterility to the whole affair, reducing the series to an intellectual exercise.

And so I thought, as someone who readily grants that the prequel trilogy’s pretty crap but is inclined not to think the rest of the series is anything too impressive, I feel like I can offer a take that’s not going to get hung up on the banalities of whether the movies are any good or on arguing for their secret and intricate genius. As far as I’m concerned, Star Wars is a deeply and systemically flawed work that’s nevertheless interesting in its pathologies. One thing I will be doing, if only to force the discussion further away from the banality of comparing the original trilogy to the prequels, is to, as I said, treat the work as presented: a seven part and counting story. This doesn’t mean willfully ignoring the fact that The Phantom Menace came out twenty-two years after A New Hope (or, for that matter that A New Hope wasn’t originally called that), or doing some sort of silly narrative game where we ignore future installments entirely, but it does mean accepting that The Phantom Menace is intended to function as a beginning despite the fact that in practice the entire audience knows that Jake Lloyd’s character grows up to become one of the most iconic villains in cinematic history.

Right. Prolegomenon sorted, let’s dive in. As mentioned, I’m not going to pretend that The Phantom Menace is a good film. Its narrative logic is, charitably, bizarre, its sense of humor moronic, its acting as flat and artificial as its CGI, and very little of it comes off in a meaningful sense. Nevertheless, it’s a film that gets a ridiculously harder time than is actually justified. One of the most common refrains about it, for instance, is that it lacks a protagonist, which is nonsense on stilts. Its protagonist is clearly Qui-Gon, a fact that’s seemingly lost on people unable to imagine that the film might not focus on any of the characters it inherited from the original trilogy. The film very clearly follows Qui-Gon’s path through his final mission as a Jedi knight. This isn’t unduly tricky in the least.

But if The Phantom Menace is a film about Qui-Gon, what are we as an audience meant to learn about him? And more to the point, if The Phantom Menace seeks to use Qui-Gon as the lens through which the overall series is introduced, what are we meant to understand Star Wars to be? As many have pointed out, the initial stakes of The Phantom Menace are, compared to basically every other installment, exceedingly low – a dispute about taxation of outlying star systems. Which is to say that at the outset, as Qui-Gon’s shuttle lands upon the Trade Federation ship, that there is no particular crisis, and that we are meant to read things as representing a status quo.

This is, of course, perfectly normal. That’s how most movies work: they present a status quo, then show its disruption. So what disrupts the status quo here? The end result is obvious enough: Qui-Gon dies, and his apprentice takes on his role as well as a new apprentice. But what causes this change? Given the way that The Phantom Menace is structured as a somewhat inchoate travelogue, the disruptions consist of the major new characters that Qui-Gon encounters throughout the film. Which means Jar Jar Binks, Padme, R2-D2, Anakin (with C-3PO here being treated as an extension of Anakin as opposed to a major figure in his own right), and Darth Maul. (The actual trade federation representatives and Darth Sidious are important in their own rights, but don’t really cross Qui-Gon’s path directly.) So the question becomes how each of these five characters disrupt Qui-Gon’s status quo, and what can be inferred from this.

Let’s go in order, if only to get Jar Jar out of the way. Obviously Jar Jar’s primary role in the film is to provide comic relief and, secondarily, to introduce the frustratingly common George Lucas trope of creating aliens as crass racial caricatures. But it’s still interesting that Jar Jar comes first in the sequence. Whatever other transformations to the status quo unfold over the course of The Phantom Menace, Jar Jar is where it all begins. It would be giving Lucas too much credit to suggest that Jar Jar is deliberately annoying, but on the other hand, he’s pointedly a character we’re meant to have a degree of distance from. He is meant to be looked at rather than engaged with, hence his broad physical comedy, ostentatiously unclear speech, and, in 1999, status as a feat of technical wizardry. More to the point, and in common with C-3PO, the character in the saga he has the most obvious resemblance to, Jar Jar isn’t a character the audience is invited to agree with so much as a voice of error – a mouthpiece for views the film wants the audience to acknowledge the existence of without embracing. (In this regard it’s notable how similar in comedic style Anakin’s “accidentally flying the ship” routine is.)

In the case of Jar Jar Binks specifically, this does not amount to much. Where C-3PO straightforwardly serves as a naysayer to the idea of having an adventure plot, Jar Jar does not express any specific viewpoint that demands to be taken seriously (although he is used for this purpose in Attack of the Clones). His function is more generally that of Brechtian psychopomp, introducing the alienation with which the film is to be watched. And, more to the point, his function is for this alienation to extend to Qui-Gon, making him a protagonist we observe from a distance, more like a subject undergoing an experiment than like a character we empathize with. We are invested in how he does, rooting for him even, but we are not particularly expected to care about the things he cares about.

Although the next character to intersect Qui-Gon’s path is Padme, this fact is initially obscured by the games the film plays with her decoys. These games are, at least in narrative terms, arguably the most important part of her character in this film, in that they train the audience to look for characters hiding as other characters, and thus to identify that Ian McDiarmid is playing both Chancellor Palpatine and Darth Sidious, a fact that’s at once crucial to the film and relatively downplayed, as befits his eponymous status as a phantom menace.

But Padme also serves the important function of illustrating many of the deficiencies of the status quo, or at least of the Galactic Republic. This does not simply mean the “turmoil” of the opening crawl, but the systemic impotence of the Republic’s political apparatus in the face of it. Which, of course, includes Qui-Gon, who is on this mission as an agent of the Republic, and whose persistent big fish problem is a straightforward demonstration of is ineffectiveness. But while Qui-Gon spends the film exploring this ineffectiveness via an action-adventure plot, Padme, once her identity is actually established, follows a parallel plot in which she engages directly and at length with the political apparatus itself, lobbying the Senate, arguing with the Trade Federation, and generally actually being a head of state in a corrupt democracy that’s far closer to collapse than it realizes. She only ever does this in her capacity as a side character, and so the engagements do not really have much depth beyond their basic expository functions, but they are at least coherent and effective at these functions, which is more than you can say for Jar Jar.

From an audience perspective, however, Jar Jar Binks is followed by R2-D2, a character with which he shares far more obvious similarities. On the one hand R2-D2 is, like Qui-Gon’s apprentice Obi-Wan Kenobi, a character who the audience knows already, and the film basically assumes that. His debut is played with a deliberate structure of anticipation and payoff: there’s a mechanical problem and various droids that resemble R2-D2 but aren’t try and fail to fix it before the real thing shows up. But the effect of this for the production-aware viewer (which is to say basically everyone) goes beyond a mere thrill of recognition, iconic a cultural figure as R2-D2 may be. Unlike Obi-Wan, whose narrative role in the prequel trilogy was made necessary by the original trilogy, nothing about R2-D2’s appearance here is anticipated by the pre-existing mythos. In A New Hope R2-D2 appears to be a near-random choice of droids on Princess Leia’s ship, and nothing through Return of the Jedi changes that. In one sense this means that R2-D2 is raw fanservice, but his elevation to a constant part of the Star Wars mythos on the level of Skywalkers or lightsabers is a significant change to that mythos.

Fittingly (and intelligently) this matches with his actual function within The Phantom Menace. There is an entertaining fan theory about R2-D2 being the true embodiment of the Force – a joke on a similar level to the “Jar Jar Binks is the true Sith Lord” theory. And like that theory, there’s an element of truth to it under the archly overplayed hand. Like Jar Jar, he is a character who is looked at, rather than empathized with, his whirrs and beeps an even more malformed version of speech than all the “meesas.” And where Jar Jar is introduced as a bumbling and incompetent fool, R2-D2 is precisely opposite: a hyper-competent force of providence that validates Qui-Gon’s vague assertions about the Force even if it does not directly relate to it. Indeed, note how soon after his arrival we get the famously technobabble explanation of the Force, further encouraging us to read R2-D2 as tacit evidence of its power.

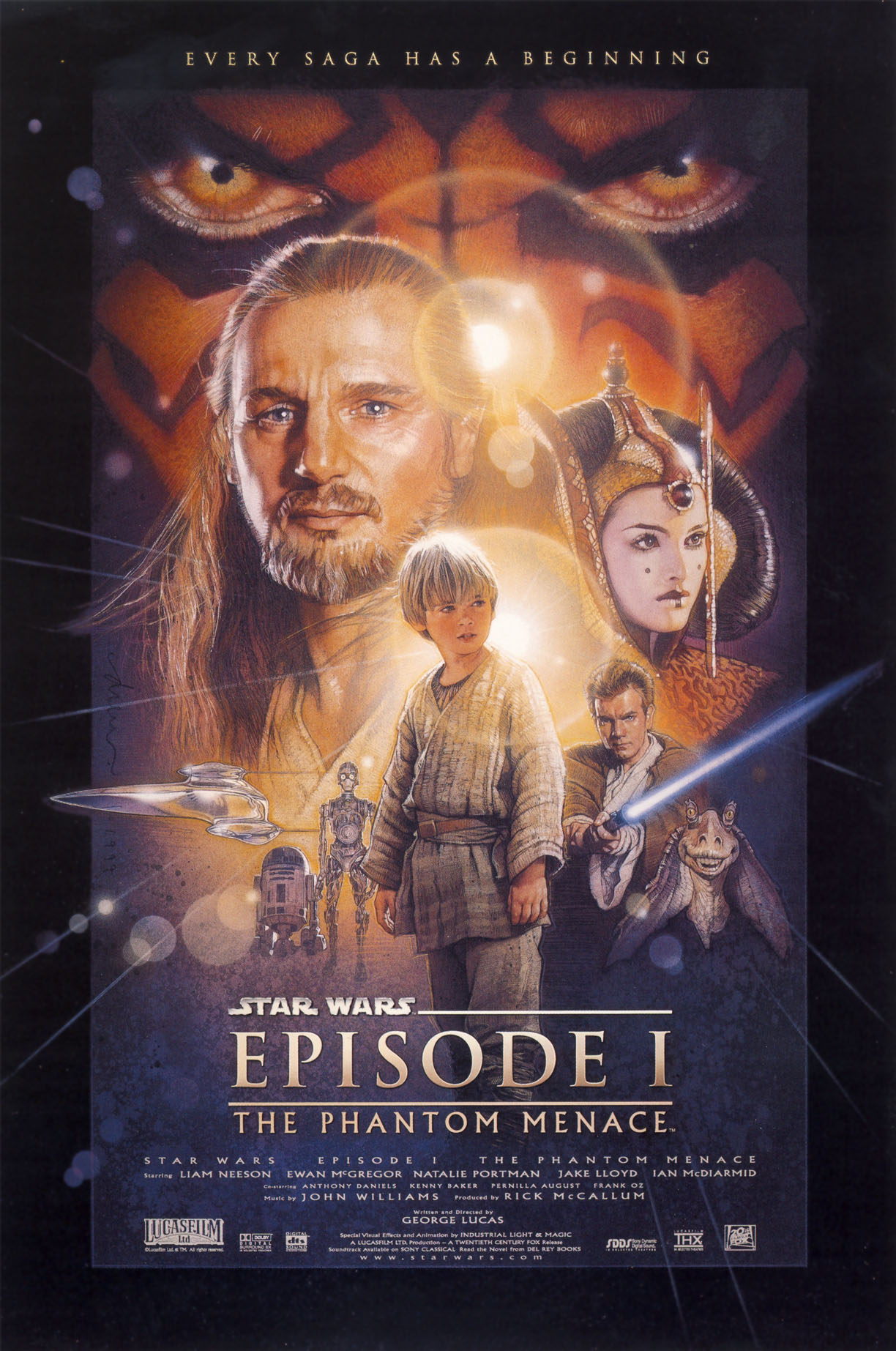

This, of course, brings us to Anakin, around whom the entire film revolves. This is not a subtle thing – the way in which the film weirdly derails when it reaches Tatooine is infamous. For most viewers, he’s is the entire point of the film; certainly the poster puts him front and center. In many regards, he’s got an even better claim than Palpatine to be the phantom menace. Or at least he would if there were actually anything in the film that particularly flagged him as such. Instead he is basically another annoying comic relief character in the mould of Jar Jar, used as the macguffin to stage the ridiculously gratuitous podrace sequence.

But it is here, more than almost anywhere else in the film, where the mythic unspoiled viewer has something of an advantage. To such a figure Anakin would appear much like Jar Jar Binks, with Tatooine not seeming meaningfully different from Gunga City. Except that instead of the mildly begrudging patience Qui-Gon shows to Jar Jar, he is immediately obsessed with Anakin. And for an unspoiled viewer, Qui-Gon’s interiority, faint a thing as it may be, is still the most fully realized thing in the film. And so the way in which the film slows down for the Tatooine sequence naturally leads the focus to shift there, with the audience being invited to at least go so far as to imagine Qui-Gon’s perspective. The fact that this perspective is motivated primarily by some readings on his tricorder still keeps us at a remove from him, but it’s clear that there’s something going on with Anakin (in a way there wasn’t with Jar Jar) and that Qui-Gon considers this on the whole more important and interesting than whatever was going on with Naboo.

Indeed, to an unspoiled viewer the typical complaint about this sequence – that Qui-Gon’s plan is contrived and high-risk – largely evaporates, with the implication pretty clearly being that Qui-Gon has simply seen the future in the way that Obi-Wan and he talked about at the beginning of the film, knows Anakin will win, and so views the podrace as a mildly convoluted but basically straightforward way to deal with their mechanical problems. This frees the unspoiled viewer to be troubled by a different failing of Qui-Gon’s, namely his reaction to the fact that Anakin is a literal slave. This reaction being essentially indifference.

This cannot be taken as some sort of sloppiness. There are many ways in which Lucas is politically naive at best and gruesomely offensive at worst, but given the series’ explicit moral focus on the rise of fascism there is no way that the question of slavery’s moral acceptability can be set aside, especially when the film has Jake Lloyd reverentially ask if Qui-Gon’s come to free the slaves. And so Qui-Gon’s refusal to go to anything like the lengths he’ll go to in order to resolve a trade dispute in order to do so becomes a highly visible failing – a moral rot at the heart of Jedi ethics to parallel the Republic’s own failings.

But while it’s deliberate, it’s ultimate meaning ends up disappearing into the black hole of indeterminability that is Anakin’s busted messiah narrative. On the one hand, the Jedi Council is spot-on that this is a terrible idea, in which case Qui-Gon’s poor judgment in wanting to train Anakin is inseparable from his poor moral judgment. And yet Anakin really is predestined – a virgin-born messiah figure every bit as powerful as the prophecies say, and thus presumably inevitable. If such a figure is a negative messiah – which is on the whole what Anakin is – then his status as a traumatized slave becomes more unruly than Lucas can deal with. Relatively coherent readings can be constructed within the context of The Phantom Menace alone, most obviously that if the Jedi had stood up to slavery their messiah wouldn’t be so heavily traumatized and thus corruptible. But even this ends up linking trauma to corruption in a way that can charitably be described as “unsatisfying.”

Thankfully the Sith are on hand to introduce a nice strong dose of moral certainty. Although I gather he acquires some depth in the Star Wars Rebels cartoon series, which you’ve got to be kidding me if you think I’m watching, in The Phantom Menace Darth Maul is a preposterously straightforward character, signifying “evil” and “badass” with equal lacks of nuance or compromise. His introduction to the main plot thus neatly absolves the film of having to continue to probe the moral complexities of passively tolerating slavery, and indeed is arguably placed where it is to accomplish precisely this.

With the film’s now ambiguity-free morality in place Darth Maul can be allowed to kill Qui-Gon, marking the first time in the saga that the role of protagonist is passed on, with Obi-Wan set to take the role for the next film. The initial arc of the story is also set at this point: by killing Qui-Gon the Sith demonstrate their ability to destroy the status quo, which sets up expectations for their rise over the next two films. This tension is expressed almost perfectly in the film’s final shot, a piece of grim irony far more elegant than The Phantom Menace usually gets credit for being, as Boss Nash boisterously thunders “PEACE!” while the audience becomes acutely aware that’s not what they’re going to be getting.

Ranking (Because I Might as Well)

- The Phantom Menace

January 30, 2017 @ 11:51 am

Red Letter Media Shit? You don’t think they make any good points?

January 30, 2017 @ 2:02 pm

I think their hectoring, nitpicking style is so conceptually bankrupt that it doesn’t matter if they do.

January 30, 2017 @ 6:06 pm

Since I’m generally a fan of their work, I just want to pitch in that the style of the Plinkett videos doesn’t inform the entirety of their output – their Half in the Bag reviews and related videos are generally more balanced (I would confess a preference for your analytical ethos if I were forced to choose, however :P). Not sure if you’d have seen any of their other stuff, but I do feel that it gets a bad rap due to the Plinkett videos at times – their style has matured a bit over the years. All a matter of opinion of course.

Defnitely worth a look, if you haven’t seen it, is the short, sweet, and beautifully made two-hour Genndy Tartakovsky Clone Wars series from the early noughties – while it has its limitations, and probably a few of the franchise’s wider ethical failings (it’s been a while since I last saw it), I’d consider it overall the best representation of the possibilities of the Star Wars universe in visual media form. There’s no bad CG animation, either 😉

January 31, 2017 @ 10:04 am

I really enjoyed their Half in the Bag Rogue One review, where the first five minutes is just them screaming “ITS A THING I KNOW I KNOW WHAT THAT IS THEREFORE IT IS GOOD” and singing “AT-ST AT-ST”

Their faux podcast Nerd Crew is also amazing

January 30, 2017 @ 12:13 pm

Interesting read. I think the best thing that can be said in the prequels’ favor is that they are automatically more interesting than most big-budget releases due to the overwhelming influence of Lucas’s creative personality. They’re bad, but they’re creatively bad, and so they stick in the mind years after most critical misfires would have been forgotten. There’s a certain value in that, especially in the era of bland superhero saturation.

“The most common type is of course the brutal and sneering takedown, an approach that usually ends up committing so totally to its brutality that it gives up on making actually interesting points in favor of preening snark.”

The RedLetterMedia series on the prequels are an ur-example of this, of course, but a saving grace for me is that they were signposted from the beginning as entertainment first and critique second (From the very first line, “Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace is the most disappointing thing since my son”). And it seems like they’ve continued to make an effort to resist being taken seriously as film critics, which I can also respect.

It’s been years since I stopped using them as an actual point of reference for anything, but I’m still struck by how well Stoklasa engages with films on a level that appeals to casual interest. The “lack of a protagonist” argument is flawed, yes, but mostly in the sense of misapplied terminology. The core of the argument is not far off the actual mark – Qui-Gon comes off as a character so lacking in interiority that it feels like he has little agency in the film, even though his freeing of Anakin makes him a pivotal player in the saga.

February 1, 2017 @ 11:50 am

I don’t know, their takedowns of Baby’s Day Out and Cop Dog were pretty well crafted pieces of criticism.

January 30, 2017 @ 12:55 pm

I take it from your repeated use of the number seven that you will not be covering Rogue One. (Or the most interesting of the Star Wars films: the one with Bea Arthur and Jefferson Starship.)

January 30, 2017 @ 2:01 pm

It’s not presented as part of the series per se, and also still in theaters which makes it a pain in the ass to go check details when writing about it, so nah.

January 30, 2017 @ 10:12 pm

Ok, but surely there’s some enjoyment to be derived from delving into the Star Wars Holiday Special…?

February 1, 2017 @ 7:34 pm

One might think so, but…

January 30, 2017 @ 3:01 pm

The Phantom Menace isn’t precisely bad…it’s just bland. That and it at once fails to follow what Lucas himself signposted in the original trilogy AND fails to properly signpost for the future of this trilogy.

Take the slavery aspect of Tattooine, which is something that never really comes up again in the prequels minus an off hand line about Anakin’s mother being freed from slavery after she’s sold, and didn’t exist in the original trilogy. The notion is that the fact that slavery even exists in the Republic is a red flag that something is very wrong in the galaxy in the first place, and that corruption is rife and something needs to be done. But it’s essentially ignored; Anakin being a slave is merely a plot complication to be overcome, not a moral quandary for the Jedi to deal with. By the time we return to the planet, a decade later in the story, slavery is barely mentioned and isn’t even a factor by Episode IV.

And that’s a fundamental flaw in the entire series; Lucas not lining up his prequels with the rest of the series. Episode IV’s description of Anakin, through Obi-Wan and through the lines given about him from Owen and Beru, suggest Obi-Wan met a far more older Anakin, and that there was something of an ideological dispute between Anakin and Owen. Owen, after all, is presented as being far more worried about keeping Luke on the farm and keeping his head down out of self-preservation. Making Anakin a child is clumsy and ignores what went before.

And you don’t have to be a colossal nerd to have noticed these things; Star Wars was a cultural icon twenty years old, with a recent re-release fresh in everyone’s mind. That Lucas thought he could get away with it…well, this is coming from a guy who continually edited the original trilogy endless, so he seemed to have a perception that continuity was flexible, so maybe he thought he COULD get away with it.

January 30, 2017 @ 8:16 pm

It’s not explicitly stated, but I would think Anakin being a slave as a child parallels to him becoming a slave of the Emperor as an adult. Watto seemed to be a much more benign master than Palpatine, though.

January 31, 2017 @ 12:08 am

That’s sort of what I am getting at, though the above post came while drinking morning coffee and working at waking up. Slavery is set up in the first movie to be a big theme, and arguably the intent to suggest Anakin is enslaved throughout his life is there. But Lucas essentially drops it once Qui-Gon and company leave Tattooine. Anakin’s dialogue even strongly suggests at one point that he would be the one who would return and free the slaves-he mentions a dream about it-which would have tied into the messiah narrative nicely. Yet it’s abandoned. Slavery exists in this weird bubble in the Star Wars movies-at least for non-droids-for about 30 minutes of one movie and never really gets a proper follow up.

Interestingly, the second Han Solo novel by Brian Daley does deal with slavery in the Empire era, with Han taking a job that turns out to be smuggling slaves, and does more with the morality of it than Lucas ever managed. While I get while Phil doesn’t want to get into the spin offs and the EU, it is interesting how many writers hit on things, sometimes long before Lucas tried them, and got them -right-.

February 1, 2017 @ 5:50 pm

You’re wrong, I think, in saying that slavery isn’t present outside of TPM. Slavery is everywhere in Star Wars.

Both the Confederacy’s droid army and the clone army the Republic uses to combat it are slave armies. Anakin and Padme exchange slaves (!) as wedding gifts. We’re introduced to Luke for the first time as he is buying slaves for his uncle’s plantation. Jabba has a palace full of collared slave girls.

And, of course, droid slavery is ubiquitous. It exists in every place and at every level of society.

TPM is unique insofar as it foregrounds slavery as a theme. Anakin, the innocent, is the only character in the history of the movies who suggests that freeing slaves is a thing someone might want to do. Lucas here portrays the failure to free Shmi as a tragedy in a way he never does the continuing unfreedom of R2D2.

So- why? Qui-Gon’s response to Anakin is telling. “We are not here to free slaves.” Not now, and not ever. The Jedi are not, in fact, ever anywhere to free slaves: they are not in the business of freeing slaves. They are in the business of defending queens; defending them against assassins, coups, insurrections and merchants who refuse to pay tax. The business of defending the establishment from its challengers, in other words.

That the Jedi don’t approach the problem of slavery as a moral quandary is the point. Slavery is, and Jedi are counter-revolutionaries.

This is why Anakin terrifies them, of course. He’s their messiah, and all messiahs must necessarily be revolutionaries (or what would be the point of them?). He already knows how to love, and not in the sterile, ineffectual way that the Jedi love. So of course they have to break him, reshape him, remould him (“Take that child and teach him senseless”).

It puts me in mind of that passage in The Brothers Karamazov, “The Grand Inquisitor”. Christ returns, and the Church can find no use for him. In fact, he is dangerous.

The Anakin we see when AotC rolls around is the broken down, hollowed out wreckage of a man, too terrified to love anyone. This is why we need to start with Anakin as a child: so we can see what the Jedi have managed to destroy. When he cripples Anakin on Mustafar and leaves him to be transformed into an inhuman monster, Obi-Wan is really only making literal what was already true.

So Episode One is the only Star Wars movie to address slavery because young Anakin is the only Star Wars character who cares about slavery, and he only exists in Episode One. Because Qui-Gon’s statement tells you everything you need to know, and anything more would be superfluous. Because Anakin dreamt that he returned and freed all the slaves, so they held him down and beat him until he forgot he loved his mother. Because actually fixing things is too hard, too radical, and so we must be fascists instead.

It serves in the movie not just to tell you that the Republic is failing, but why it will not- cannot- be saved.

January 30, 2017 @ 4:57 pm

The closest thing to a redemptive reading of Phantom Menace that I think we’re ever going to regret. Really looking forward to seeing how you revisit these stories over the next while – especially how the hell you plan to make something of Attack of the Clones.

But your point about Qui-Gon’s indifference to slavery reminds me of a post I remember from a few years back on Slate, about how droids are literally slaves in the Star Wars universe. (http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2013/06/droids_in_star_wars_the_plight_of_the_robotic_underclass.html) It’s an intriguing kind of issue in Star Wars. At first, I think it appeared just as a blind spot of Lucas’ – droids are machines and treated casually as property, some permitted more dignity from their owners than others. But they’re creatures with fully-developed intelligences that have no rights over how they should be treated or autonomy over how to live their lives. “We seem to be made to suffer. It’s our lot in life.”

I like how you’ve hit on this as an essential flaw of the whole series’ ethics – as a form of media itself, and in-universe. How the tolerance and acceptance of slavery – whether or organic or droid life – is an ethical failure at the heart of the Star Wars universe’s entire social order. How can the Jedi, idealized though they are, be true heroes if they so casually accept slave economies that appear wherever they go?

January 30, 2017 @ 5:29 pm

Maul isn’t fleshed out so much in “Rebels” as he is in “The Clone Wars,” which was done by a lot of the same creative people as rebels, but functions during the period between “Attack of the Clones” and “Revenge of the Sith.”

And, honestly, “The Clone Wars” is more fun and better entertainment than most of the movies are. The characterizations are way better and more thought out, and there’s a ton of interest shown in the more plebeian characters (like individual clone troopers and how they develop their own distinct personalities), all with an eye towards the pathos of the outcome that we all know is waiting down the line.

You might actually find that you enjoy “The Clone Wars” if you give it a chance.

January 30, 2017 @ 5:46 pm

Dude, I don’t even enjoy most Doctor Who spinoff material.

January 30, 2017 @ 6:18 pm

I’m consistently surprised by the quality of both Clone Wars and Rebels, but they’re very much kid’s shows of the sort I don’t think Phil is likely to enjoy given previous comments on kid’s media. There’s really nice moments scattered throughout the series, but not enough I feel like it’s sane to recommend the 8+ seasons of material to get to them.

January 30, 2017 @ 6:15 pm

One of the things I find interesting about Phantom Menace (and one of the explanations for why the film was on the whole quite liked when it came out and near-despised now) is that, devoid of any expectations for what the “prequel trilogy” would turn out to be, it actually functions quite well as a kinda fun little preamble to the Star Wars films.

Like, the whole film is kind of built with the idea that this is a totally separate story that we’re just kinda seeing the familiar Star Wars characters peeking into–hence why Qui-Gon exists as the protagonist, and why pretty much all the returning characters exist only as supporting roles. The idea isn’t so much that this is what leads directly into the 1977 film, but that we’ve gone so far back in time in the universe of the films that we’re only seeing the characters when they just start out, before they’re even the leads in their own story.

It’s all actually rather fun, and an interesting approach to the idea of a “prequel”. And it makes a lot of the really bizarre cameos (C-3PO in particular) work as just fun call-backs that are rather deliberate in their unexpectedness. The other issues of the film still exist of course–the acting is still flat, the narrative structure a hot mess, and those awful, awful, racial caricatures–but it becomes surprisingly functional when it’s not viewed as the start of a proper trilogy.

What kills it, then, is that it is the start of a proper trilogy, and the next two films are tasked with actually telling the story of how we get to the events of the original films. And since Attack of the Clones in no way meaningfully follows up on Phantom’s events and characters (it essentially hits a reset button on all the relationships, and the Clone War itself isn’t shown to really develop out of the Theed conflict), Phantom can’t help but in hindsight feel like an utter waste of time.

A shame, because I still find it the most watchable of the prequels. Part of this is nostalgia (I was seven when it came out and absolutely adored it as a kid), but I also think it’s from a visual perspective one of the prettiest of the Star Wars films (the effects here are honestly stunning), Lucas’s direction has the most vitality in the prequels here, and the whole thing is honestly so goddamned fun. It’s a big, sprawling mess of an homage to 50’s serials (probably the most indebted to them of all the Star Wars films), and I can’t help but still enjoy it on rewatch.

January 30, 2017 @ 7:40 pm

As someone who subscribes to the Ring Theory (albeit a version I constructed myself), I agree that the problem with the Phantom Menace is that it’s a great standalone that fails completely as the “start” of a trilogy. This is mostly because it’s the Happy Ending (since the prequel story has to work backwards in structure to end up in approximately the right place) so it had no foundations and thus is doomed to collapse before it even really starts.

But yeah, it’s probably the one of the prequels I can happily watch (indeed, more so than at least half of RotJ) because the production design is great, and there are some interesting attempts at retcon, which after all Lucas had to start doing with Empire and never really stopped.

January 31, 2017 @ 5:17 pm

Yeah, I’m far more likely to pop this in on a rewatch than Return–at least Phantom doesn’t majorly screw over its female characters as much (can you believe this was the first Star Wars film to pass the Bechdel test?).

February 1, 2017 @ 9:41 am

Having various major characters of no gender or unclear gender, (as far as I’m aware, Chewbacca, Yoda and the droids are never gendered, though since I’m not a massive fan I may well be missing offhand lines somewhere,) does make not passing the Bechdel test less noteworthy than it would otherwise be. Though it’s not particularly surprising, since the viewer is probably expected to think of them as “male by default” and the originals follow the “being female is a trait of deviation from normality you want in precisely one of your heroes” pattern.

February 1, 2017 @ 5:04 pm

Was just checking through scripts, and at the very least R2 is for sure gendered as a he (ESB: “Artoo expresses his relief, also”). I would bet the same for Chewie and 3PO, though I can’t say for sure yet, and considering Yoda is played by a man (and Oz is using a voice that’s not really similar to his female voices), I would doubt we’re meant to perceive them as either gender-neutral or female.

I mean, the thing is that we do consistently see female droids and aliens throughout the series (EV-9D9 and Shaak Ti come to mind), so it’s unlikely that the film intends us to assume otherwise of characters that appear to present as male.

February 1, 2017 @ 5:09 pm

Aha, further checking, all from ESB: Yoda referring to himself: “take you to him, I will”; Leia referring to 3PO: “Chewie, do you think you can repair him?”; 3PO referring to Chewie: “After all, he’s only a wookiee”.

January 30, 2017 @ 6:38 pm

I agree with those above about Red Letter Media after hearing about them on some regular podcast that I listen to. I tried to watch them, but the old bloke’s voice put me off from watching any for more than a minute. Great point about the slavery and Qui-Gon’s indifference towards it. Myself, I’ve seen these prequels over the Christmas holidays and with Lucas’ love of recreating the style and feel of his childhood serials in his ahem… style of writing and directing of actors, you get these.

January 30, 2017 @ 8:07 pm

I, for one, am glad you will not touch the spin-off material. The only Star Wars spin-off I ever saw was a public access show in San Antonio where these two guys had incredibly detailed reproductions of costumes, weapons, and a speeder bike and they recreated scenes from the movies but everything was based around jokes about chewing tobacco including making characters names puns on chewing tobacco brands. This also did this with The Shining. They were pioneers in chewing tobacco based comedy.

January 31, 2017 @ 2:52 am

Is it a moral failing of mine if I instantly found myself getting defensive for Red Letter Media, despite never having watched one of their videos?

January 31, 2017 @ 3:16 am

Not necessarily.

Now, if you felt a kneejerk reaction to defend Cinema Sins…

January 31, 2017 @ 9:02 am

I do think the point of cinema sins is that you can nitpick any movie, good or bad: they’ve done videos on films like “Fury Road”, which they liked a lot, and say as much in the video, as well as films that they openly dislike, such as the star wars prequels, and find just as many “sins” in every film. The point is that if you look hard enough, and are obsessive enough, you can find “story ruining plot holes” in any movie.

In many ways, cinemasins functions pretty well as a critique of the nitpicking fridge-logic criticism that cries “plot hole! Story ruined!” at any minor/ necessary inconsistency in a story. Although it would also be fair to argue their videos indulge in said style of criticism while trying and failing to be self aware critiques of it.

January 31, 2017 @ 8:31 am

The parallels between Star Wars and Ancient Rome are strong, and I have seen it speculated in great detail, more than once, how the story of the fall of the Roman republic, with its corrupt officials, and unwieldly governance spread too thin at the outer edges leading to the appointing of a temporary ‘Emperor’ (Julius Caesar/Palpatine) to solve an emerging crisis, who then outstayed their intended term and went on to became dictators, mirrors the main thrust of the Star Wars universe.

If we accept that as the case, then the idea of an acceptable Slave class becomes more in keeping with the overall narrative; especially when the upholders of the current rule of law, the Jedi, are more concerned with maintaining the status quo, than any moral crusade.

Our modern, western, concept of slavery is that it is (and it is) abhorrent. But for most of human civilisation (and less savoury parts of the modern world) slavery was part and parcel of human civilisation.

This is how I’ve always viewed the slavery in the Star Wars universe; as part and parcel of the Old (corrupt) Republic system and the people of the Republic are simply inured to its existence.

January 31, 2017 @ 3:20 pm

‘a moral rot at the heart of Jedi ethics to parallel the Republic’s own failings’

I may be misremembering this as being set up in Phantom Menace, but I always get confused about whether the prophesy of the chosen one balancing the force is supposed to be the Jedi’s comeuppance.

There’s surely a sense in which, as viewers of the original trilogy know, the prequels will end with two Sith and two Jedi, which seems exactly what some Delphic Oracle would mean when talking about balance. And this a state of affairs the Jedi is as active in bringing about as Palpatine is. I can’t really decide if Lucas was playing for a sense of irony here or if he really does just mean balance to be read as ‘everything is perfectly nice as the goodies see it’.

January 31, 2017 @ 6:03 pm

There’s some good evidence from interviews about what Lucas had in mind in the first two sections of the “Behind the scenes” section of the Chosen One article on the Star Wars wiki. It’s a little convoluted and was never really explained in the movies, but basically it seems as though Lucas imagined a sort of Yin/Yang like balance between the light and dark sides of the Force, but the Sith were unbalancing everything in favor of the dark side, so they needed to be destroyed to bring back the balance (in which the dark side would still exist and play a necessary role).

January 31, 2017 @ 6:31 pm

Thanks for the link.

I still don’t quite get it (and indeed feel like my head might soon explode) but I guess that’s because I hadn’t really got the Force.

I’m guessing the point is that the Sith aren’t really part of the Force, just feeding off it..?

Anyway, I suppose I can rest assured Lucas wasn’t aiming for irony.

January 31, 2017 @ 6:21 pm

” His function is more generally that of Brechtian psychopomp”

I am going to change my name by deed poll to Brechtian Psychopomp.

Yours,

Brechtian Psychopomp

February 1, 2017 @ 8:20 am

Okay, going to defend Red Letter here — or anyway, at least the particular video criticizing TPM.

1) They’re pretty clearly mixing criticism with entertainment to create a strange hybrid creature. This should not, in and of itself, be a problem. MST3K does it and we all love them, right? In Red Letter, it’s a little creepy — deliberately so — because the critical voice is a deranged serial killer who gets messages from cheese puffs and there’s a strong implicit fourth-wall breaking about the nature of fans and fandom. Also, the later Red Letter stuff was weaker and worse; they moved away from the good and clever criticism and got too caught up in the 4channish figure of Harry.

But it’s not that hard to separate the criticism from the entertainment. For instance, he takes several minutes to review Lucas’ use of two-camera dialogue. That may be basic Cinema 102 stuff, but it’s legitimate criticism. (And in this case, totally valid: Lucas signally failed to solve a problem that is regularly given as a challenge to sophomore Film majors.) And then of course there’s the “describe this character” scene, which is accurate, brutal, and tells us something important.

Arguably RLM has become too influential as the go-to cite for dismissing the prequels. But baby, bathwater.

2) Qui-Gon Jinn as protagonist: I’m really not convinced.

For starters, he’s a character who has relatively few lines, no character arc, almost never appears alone, and dies 20 minutes before the end of the movie. But more to the point, he’s not obviously a character the movie considers to be a protagonist. He doesn’t get great framing scenes. (Hell, he doesn’t even get to be front and center in the movie poster.) There are no lovely set-pieces for him. All those original-movie shots of Luke standing in front of a million square miles of desert with a look of heroic confusion on his face? There’s nothing like that for Qui-Gon. He doesn’t have any memorable moments of dignity or badassitude. The music doesn’t generally swell when he comes on. The script doesn’t give him any snappy one liners, nor either any memorable speeches or monologues. The movie tends to treat him as a plot device, not a character.

One way to check whether someone is a protagonist is to ask whether the movie works without them. No Indiana Jones, no Raiders, right? Remove Luke Skywalker… check, the original trilogy falls apart.

But could we have PM without Qui-Gon? Sure we could. Obi-Wan comes alone, escapes alone, finds the kid by himself. The tweaks required would actually be pretty minor — basically you’d need to have Obi-Wan reverse himself on taking an apprentice instead of being convinced, and Darth Maul would have to kill someone else. But that’s pretty much it.

So, I don’t think Jinn qualifies as a protagonist. IMO viewing this as a buddy film would make more sense (though it brings its own set of problems).

Doug M.

February 1, 2017 @ 4:38 pm

Based on a quick scan of the script (http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Star-Wars-The-Phantom-Menace.html), Qui-Gon gets 207 (plus or minus whatever I missed or double-counted) lines of dialogue, as opposed to Anakin’s 181, Jar Jar’s 87, Obi-Wan’s 73, and Padme’s ~60 (I can’t remember offhand if Padme is being Amidala in any of the scenes after act 1 or if it’s all Sadbe).

At any rate, the number of lines of dialogue don’t necessarily tell you your protagonist, depending on how stoic they are; The Man With No Name and Ogami Itto jump to mind. He gets a number of cool hero moments in the story, particularly in the climax (where Obi-Wan really is more of his assistant trying to keep him most of the way). And several of Qui-Gon’s quotes are memorable —

“There’s always a bigger fish,”

“The ability to speak does not make you intelligent.”

Obi-Wan: Master Yoda says I should be mindful of the future.

Qui-Gon: But not at the expense of the present.

And the last one speaks to how he’s important for this film. The Jedi in the prequels are a decayed institution that has long since lost sight of its true mission to play its political games with the Senate. Qui-Gon hasn’t entirely lost sight of the people he’s supposed to protect. He doesn’t want to overthrow the system or anything, but he’s more than willing to bend the rules. And he genuinely cares about the people at the bottom of the rung. It’s why he goes out of his way to save Jar Jar despite not particularly liking him, why he saves Anakin, and why he dies pointlessly in a battle that doesn’t mean much in the big picture, which keeps him out of the way of Palpatine in the next two films.

Compare him to Obi-Wan, the most consistently well-written and well-acted character in the prequels. Obi-Wan is in many ways the ideal Jedi Knight, but he’s absolutely a loyal tool of the system. It’s child’s play for Palpatine to keep him on the other side of the galaxy from whatever he’s up to; Obi-Wan goes where he’s ordered and does his mission. (For Lucas, The System is always the ultimate villain — see especially THX1138)

So if you made Obi-Wan the hero of TPM, he probably wouldn’t rescue Anakin (though he’d report the presence of slavery to the authorities, who would promptly do nothing), almost certainly wouldn’t try to surreptitiously train him (he basically does so because of Qui-Gon’s dying wish), and he definitely wouldn’t rescue Jar Jar. The combination means the climactic battle likely goes the other way.

On the other hand, if you rewrite him to be less a cog in the machine and a wiser hero like Qui-Gon, he’d probably see through some of the cracks and fissures that tear everything down. For one thing, a Qui-Gon-type would be more in touch with the way the Jedis’ suppression of emotion in favor of focus could break someone as compassionate as Anakin, and Episodes II & III would have an Anakin who could channel his passion instead of being torn apart by it at every turn. He probably wouldn’t be a deeply sensitive, emotional kid traumatized into a an emotionless, murderous automaton of the system. Palpatine’s going to go through with his plan regardless, but he’s not going to have such a perfect apprentice right there — he’ll have a backup if Dooku goes down, of course, but no one with that perfect combination of immensely powerful and utterly vulnerable.

But, you know, I like the prequels, warts and all, so take what I say for what it’s worth.

February 8, 2017 @ 8:05 pm

“Like Jar Jar, he is a character who is looked at, rather than empathized with, his whirrs and beeps an even more malformed version of speech than all the ‘meesas.'”

I must respectfully but strenuously disagree.

The brilliance of R2D2 is that he is the most expressive character of the saga despite his lack of vocabulary or facial expressions. Those whirrs and beeps always tell us exactly what his state of mind is.