Praxeus Review

Let’s start with the biggest upsides. The story did not end by suggesting environmentalists were the real problem. It didn’t conclude that disabled people should use fewer straws. Indeed, politically it was basically ideal—a clear moral and ethical point that was the backdrop for an actual adventure instead of being sledgehammered in a “the moral of this story was” ending. And on top of that, it had well-defined characters and a coherent plot.

Obviously this is Stockholm Syndrome. Once again we are in the position of being pleasantly delighted that a story has come in at “vaguely competent” with a minimum of trauma. Even better, it’s done it three stories in a row, two of them rewritten by Chibnall. (Who has apparently managed the impressive feat of rewriting every person of color on staff this year, given next week’s credits.) This feels like a result, and while we know it shouldn’t, that’s where we are.

Nevertheless, it’s harder this week to really revel in an adequate job done more or less competently than it has been for the past two. Mostly this is down to small things. To do an extreme globe-hopping adventure in Doctor Who always feels a bit pointless—using the TARDIS as an airplane feels rather like bringing a Tissue Compression Eliminator to a knife fight. And as a result none of the locations really resonate—nothing feels like a distinct or coherent place. The (momentarily quite interesting) decision to fully split up the TARDIS crew evaporates quickly, and instead we just ping pong among locations with more vigor than coherence. The longstanding tendency of the new series’ acceleration to make Doctor Who’s genre-hopping into an exercise in reducing every genre to a Doctor Who story here becomes something far more insidious, where everywhere in the world ends up feeling like a diversity-minded portrayal of the United Kingdom.

Whittaker also feels particularly on autopilot here. McTighe and Chibnall end up writing her as a collection of tics, and Whittaker finds herself lost in it, left with nothing to do but do the same basic “I have part of a plan” joke on repeat in between outbursts of particularly bad technobabble. This becomes something of a masterclass in how not to do a female Doctor—there’s what feels like a conscious decision not to make her angry or troubling at any point, and so she’s left to talk about humanity poisoning itself with microplastics with a big enthusiastic “I love teaching science” grin on her face. It’s instructive to imagine how much the testiness of Capaldi’s Doctor would help here—how much the “we don’t have time to mourn” bit out of Mummy on the Orient Express could have smoothed over the “Gabriela fails to really be very upset about her best friend dying” plot, for instance, or even just how a Doctor who was actually furious at Suki’s actions could have better set up the effort and failure to work with her in the climax so that it didn’t feel perfunctory. (And let’s not even talk about doing the “martyr yourself piloting the vehicle on a suicide mission” trope in the wake of Clara’s hairtie bit in Flatline.)…

It’s May 20th, 1967. Between now and July 1st, a department store in Brussels will burn down, killing 323, 72 will die in a plain crash in Stockport, 34 will die on board the USS Liberty in an accidental Israeli attack, and the Six Day War will happen, which result in a death toll on the order of 14-20,000.

It’s May 20th, 1967. Between now and July 1st, a department store in Brussels will burn down, killing 323, 72 will die in a plain crash in Stockport, 34 will die on board the USS Liberty in an accidental Israeli attack, and the Six Day War will happen, which result in a death toll on the order of 14-20,000. It’s June 25th, 1966. Between now and July 16th, a three-year-old girl will die at the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison, Wisconsin after crawling under a restraining fence and being pulled into an elephant cage. Hundreds will die across the midwestern United States in a six-day heat wave, including 149 in St. Louis, and as many as 650 in new York City. Eight student nurses will die in Chicago when Richard Speck breaks into a dormitory and strangles them. This is in addition to numerous deaths in the Vietnam War, the deaths of Polish poet Jan Brzechwa, French painter Julie Manet, and the world edging ever closer to the eschaton. Also, The War Machines airs.

It’s June 25th, 1966. Between now and July 16th, a three-year-old girl will die at the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison, Wisconsin after crawling under a restraining fence and being pulled into an elephant cage. Hundreds will die across the midwestern United States in a six-day heat wave, including 149 in St. Louis, and as many as 650 in new York City. Eight student nurses will die in Chicago when Richard Speck breaks into a dormitory and strangles them. This is in addition to numerous deaths in the Vietnam War, the deaths of Polish poet Jan Brzechwa, French painter Julie Manet, and the world edging ever closer to the eschaton. Also, The War Machines airs.

CW: Rape

CW: Rape It’s March 27th, 1965. Between now and April 17th, 470 people will die in a dam burst and landslide in Chile, 20 will die when a car bomb is detonated outside the US embassy in Saigon, two will die when the first aircraft lost in air-to-air combat during the Vietnam War are shot down during a strike on the Thanh Hóa Bridge, and somewhere north of 250 people will die in the Midwestern United States in what are called the Palm Sunday Tornadoes, while Richard Hickock and Perry Smith will be executed by hanging for the murders of the Herbert Clutter family, Princess Mary wll die of a heart attack on the grounds of her estate at Harewood House, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Crusade airs.

It’s March 27th, 1965. Between now and April 17th, 470 people will die in a dam burst and landslide in Chile, 20 will die when a car bomb is detonated outside the US embassy in Saigon, two will die when the first aircraft lost in air-to-air combat during the Vietnam War are shot down during a strike on the Thanh Hóa Bridge, and somewhere north of 250 people will die in the Midwestern United States in what are called the Palm Sunday Tornadoes, while Richard Hickock and Perry Smith will be executed by hanging for the murders of the Herbert Clutter family, Princess Mary wll die of a heart attack on the grounds of her estate at Harewood House, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Crusade airs. Song for Eric (demo, 1990)

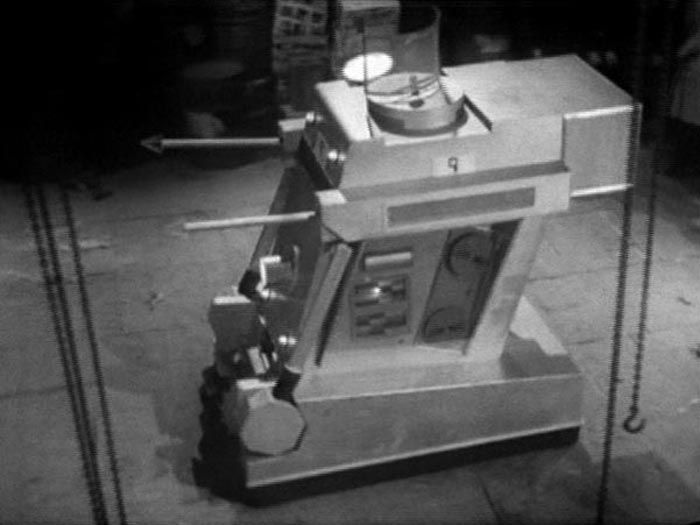

Song for Eric (demo, 1990) It’s December 21st, 1963. Between now and February 1st, 1964 128 people will die in a cruise ship fire north of Madeira, 25 people will die in riots in the Panama Canal Zone, 100 will die in anti-Muslim riots in Calcutta, three will die when an American fighter jet accidentally strays into East German space and is shot down, while Pamela Johnson will be murdered in Manchester, New Hampshire, T.H. White will die of heart failure, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Daleks will air on television.

It’s December 21st, 1963. Between now and February 1st, 1964 128 people will die in a cruise ship fire north of Madeira, 25 people will die in riots in the Panama Canal Zone, 100 will die in anti-Muslim riots in Calcutta, three will die when an American fighter jet accidentally strays into East German space and is shot down, while Pamela Johnson will be murdered in Manchester, New Hampshire, T.H. White will die of heart failure, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Daleks will air on television.