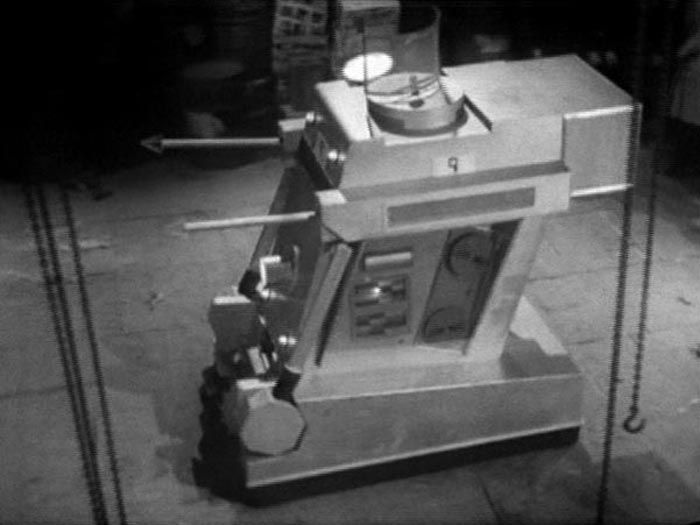

I Made My Madness Reality (The War Machines)

It’s June 25th, 1966. Between now and July 16th, a three-year-old girl will die at the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison, Wisconsin after crawling under a restraining fence and being pulled into an elephant cage. Hundreds will die across the midwestern United States in a six-day heat wave, including 149 in St. Louis, and as many as 650 in new York City. Eight student nurses will die in Chicago when Richard Speck breaks into a dormitory and strangles them. This is in addition to numerous deaths in the Vietnam War, the deaths of Polish poet Jan Brzechwa, French painter Julie Manet, and the world edging ever closer to the eschaton. Also, The War Machines airs.

It’s June 25th, 1966. Between now and July 16th, a three-year-old girl will die at the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison, Wisconsin after crawling under a restraining fence and being pulled into an elephant cage. Hundreds will die across the midwestern United States in a six-day heat wave, including 149 in St. Louis, and as many as 650 in new York City. Eight student nurses will die in Chicago when Richard Speck breaks into a dormitory and strangles them. This is in addition to numerous deaths in the Vietnam War, the deaths of Polish poet Jan Brzechwa, French painter Julie Manet, and the world edging ever closer to the eschaton. Also, The War Machines airs.

Looking at it in 2020, the two things that jump out about The War Machines are how prescent it is and how prescient it isn’t. On the one hand, its basic concerns about the destructive possibilities of computer technology are clearly ahead of its time. It’s not that evil computers were unknown in 1966—they started appearing in sci-fi literature in the 1950s, the same decade that Alan Turing broached the subject of whether a machine could think in his landmark paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” But the consequences of artificial intelligence were still firmly a niche concern, and The War Machines focus on them has more in common with the world a half-century later on than a lot of what’s around it in the series. That this is by the same writer as the bewilderingly blackface-based race reversal of The Savages immediately before it and was filmed just before the vapid piratical adventures of The Smugglers after it feels like a more profound juxtaposition than Doctor Who usually manages.

And yet on the other hand, much about The War Machines has aged poorly. The fundamental clumsiness of the computer, with its tediously slow synthesized speech, the even more clumsy War Machines, the weird overlaying of mind control onto the computer plot, all of this feels like an aggressively outdated bit of kitsch, which, to be fair, it unquestionably is. It is ahead of its time, but not nearly far enough ahead to avoid feeling comically outdated.

On top of this tension, meanwhile, it shares The Daleks’ odd suspension between two apocalypses, although unlike The Daleks it focuses primarily on the ideologies involved instead of on the eschatons themselves. On the one hand, you have a computer named after Germanic gods, a point Ian Stuart Black doubles down on in the novelization by having the first War Machine be named after the Valkyries. Norse paganism isn’t always a marker for Naziism, but when you’ve got men shouting at the camera about their Teutonic digital master’s plan for world domination, well, to quote Tat Wood and Lawrence Miles, “it’s all looking a bit Nazi.”

But as Wood and Miles immediately turn around and note, other factors point towards standard rhetoric about Communism, most obviously Polly’s brainwashed comments about how she loves to work for a cause, and for that matter the brainwashing in general.…

CW: Rape

CW: Rape It’s March 27th, 1965. Between now and April 17th, 470 people will die in a dam burst and landslide in Chile, 20 will die when a car bomb is detonated outside the US embassy in Saigon, two will die when the first aircraft lost in air-to-air combat during the Vietnam War are shot down during a strike on the Thanh Hóa Bridge, and somewhere north of 250 people will die in the Midwestern United States in what are called the Palm Sunday Tornadoes, while Richard Hickock and Perry Smith will be executed by hanging for the murders of the Herbert Clutter family, Princess Mary wll die of a heart attack on the grounds of her estate at Harewood House, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Crusade airs.

It’s March 27th, 1965. Between now and April 17th, 470 people will die in a dam burst and landslide in Chile, 20 will die when a car bomb is detonated outside the US embassy in Saigon, two will die when the first aircraft lost in air-to-air combat during the Vietnam War are shot down during a strike on the Thanh Hóa Bridge, and somewhere north of 250 people will die in the Midwestern United States in what are called the Palm Sunday Tornadoes, while Richard Hickock and Perry Smith will be executed by hanging for the murders of the Herbert Clutter family, Princess Mary wll die of a heart attack on the grounds of her estate at Harewood House, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Crusade airs. Song for Eric (demo, 1990)

Song for Eric (demo, 1990) It’s December 21st, 1963. Between now and February 1st, 1964 128 people will die in a cruise ship fire north of Madeira, 25 people will die in riots in the Panama Canal Zone, 100 will die in anti-Muslim riots in Calcutta, three will die when an American fighter jet accidentally strays into East German space and is shot down, while Pamela Johnson will be murdered in Manchester, New Hampshire, T.H. White will die of heart failure, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Daleks will air on television.

It’s December 21st, 1963. Between now and February 1st, 1964 128 people will die in a cruise ship fire north of Madeira, 25 people will die in riots in the Panama Canal Zone, 100 will die in anti-Muslim riots in Calcutta, three will die when an American fighter jet accidentally strays into East German space and is shot down, while Pamela Johnson will be murdered in Manchester, New Hampshire, T.H. White will die of heart failure, and the world will edge incrementally closer to the eschaton. Also, The Daleks will air on television. Tear in Your Hand (1992)

Tear in Your Hand (1992)