The Final Problem Review

I know, I said this wouldn’t be up for Monday. But then my weekend plans got spoiled by a stomach bug and I ended up home and watching Sherlock anyway. So it’s entirely possible that I’ve got a sour mood to match my stomach. Nevertheless, what a complete and utter disappointment this season of Sherlock has been.

The crux of the problem is one that plenty of franchises have fallen afoul of, which is thinking that you can introduce a character like Eurus and have her matter to the audience purely on the mythic weight of who she is instead of having to develop her. But it doesn’t work. She’s a distressingly one-note character whose characterization consists entirely of Mycroft asserting things about her. More to the point, her supposed powers are all bizarrely undersold: we’re told that she can effectively enslave someone by talking to them, but nothing about her comes off as particularly persuasive or charismatic. Mostly she sits around talking like a Markov bot fed on mediocre nihilist philosophy. And this is a real problem – the episode depends on her being the unholy fusion of Sherlock and Hannibal, but instead she’s just a generic megalomaniac. Which makes the resolution of her just needing a hug painfully unearned.

Making this worse is the way in which the episode is haunted by Moriarty. It’s not that it would have been better to actually bring him back, but having him popping up on video screens for dramatic effect and to have been the secret co-architect of all of this only serves to highlight how much weaker Eurus is as a villain. I’m not sure even Magnussen could have been effective with Andrew Scott popping up all over his episode, but Eurus doesn’t stand a chance, and the overall effect is to constantly remind the audience of a time when the show hadn’t used up its best ideas yet.

It’s not that there aren’t good bits. The relatively bottle-episode nature of it such that the majority of it is just Sherlock, John, and Mycroft is good, and all of them get some lovely character moments throughout. Mycroft, in particular, shines, getting a wealth of small emotional moments of the sort that he hadn’t really had before in the series. But John’s incredibly well-used as well, even if I don’t entirely buy him backing down from shooting the warden. And of course Molly’s scene was incredible.

But none of that masks the fact that this is just The Great Game done over with the melodrama pushed past the breaking point. The reveals just don’t work. The big one – that Redbeard was actually a person that we’ve never met before and aren’t particularly invested in – is a complete flop. We’ve already seen five people get murdered this episode. Finding out some kid from Sherlock’s past got killed instead of his dog doesn’t carry any particular weight. If anything, it was easier to be upset when it was a dog, which at least felt like a fairly fleshed out dog.…

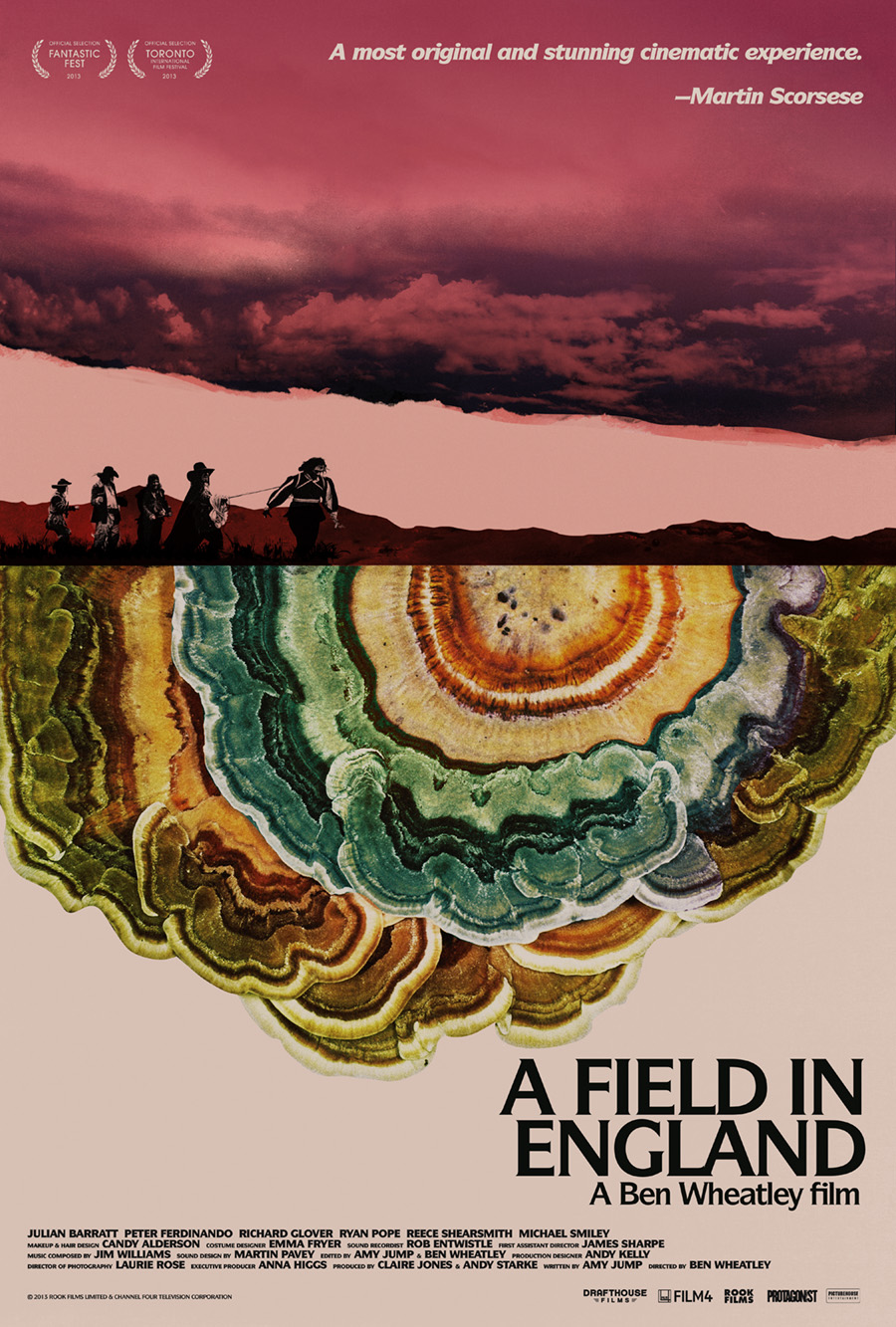

Wandering in open country is naturally depressing

Wandering in open country is naturally depressing a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration

a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration