Elizabeth Sandifer

Posts by Elizabeth Sandifer:

Basilisk a Reaction

I’ve been blasting review copies of Neoreaction a Basilisk (currently available on Kickstarter) out to the world, including an open offer to send it to Yudkowsky-style rationalists and neoreactionaries if they want to trash it. So here’s a roundup of the reaction it’s gotten, which has mostly been within the rationalist community so far. (But do stick around for the end, where there’s one great big of neoreactionary response, and an announcement of a new stretch goal.)

First, though, the big one, whcih is that Eliezer Yudkowsky weighed in on the book’s existence. Well. Sort of. Actually he told everyone to stop talking about the book while referring to it only as “[CENSORED].” Say what you like about the man, he’s at least very consistent in his reaction to basilisks. I’m sure it’ll work just as well.

Meanwhile, in the “good reviews” department, Tom Ewing, of the mad and epic blog project Popular, penned this very insightful, funny, and complimentary review, which I 100% promise you that you will want to stick around for the last line of. No, no. Don’t skip ahead. Just let it happen.

Tumblr user nostalgebraist wrote a lengthy series of posts on it, of which this is the last one (but it has an index of the whole thing at the start). It’s a mixed review in terms of what it thinks of the book, though I’m inclined to think it makes the case for the book just by having such a lengthy and nuanced engagement with it. It definitely sent me back to the draft manuscript to shore up and tinker a few passages, and is a thoroughly good read. (Nostalgebraist is also the author of The Northern Caves, which is by many accounts brilliant, and which I’m hoping to get to and write about, but you know how the schedule is these days.)

Also on tumblr was psybersecurity’s three-part review (again linking to the last part as it has an index). The main review (the post with review in the title, that is) is what I described as a “good bad review,” which is to say that it makes a serious effort to understand what the book is doing and has entirely sensible and justifiable reasons for it not being his cup of tea. The post actually linked, “Pwning Sandifer,” is a middling deconstruction, but middling is a hell of a good result for your first effort at deconstruction, and it’s worth reading for bit where it gets entertainingly excitable in its sheer horror that anyone would ever say the things that Thomas Ligotti says, culminating in a declaration that Ligotti is “nothing more than pure unadulterated evil,” italics his.

In a similar genre of “Yudkowsky fans attempt to pastiche the literary style of Neoreaction a Basilisk” is socialjusticemunchkin’s sort-of-ten-part review, which I link to Part 8 of, again because it has the index of the whole thing. In a reasonably clever joke about Mencius Moldbug’s failure to ever write Part 9c of A Gentle Introduction to Unqualified Reservations, Part 9 was deliberately excluded.…

Comics Reviews (May 11th, 2016)

All-New All-Different Avengers #9

Confusion over whether I had dropped this for Standoff or for good meant it was in my pulls today, so I figured why not. Answer: because this is simply a bad comic. An issue anchored by a Jarvis-level perspective in which Jarvis is a figure of cartoonish, stupid excess. The result is that all emotional resonance the book has is that Jarvis is screaming bloody murder at the newly introduced Wasp, a cipher of a character with outsized potential for a fridging or heel turn. (And is Janet dead again?) Meanwhile the larger book is all Kang and superhero neoclassicism, while the new bunch characters remain basically wasted; Waid is depressingly incapable of writing either Ms. Marvel or Miles Morales well. Add Asrar’s bland and flat art and you have a complete waste of a good book. Definitely drop for good.

Silk #8

Spider-Women is back on track, with an issue that actually makes a semi-compelling case for reading Silk by dovetailing nicely into what was apparently the book’s pre-crossover status quo as the Black Cat dramatically enters the plot. Meanwhile, the overall arc is elegantly poised for Jessica Drew to come back into the narrative. Really, everyone seems set to come out of the crossover on interesting and compelling terms. I’m still utterly unsold on Silk as a character, but when I hit post on this I’m going to quickly check if Robbie Thompson is writing anything else, cause he’s good.

Black Panther #2

Ta-Nehisi Coates is still awkward – he’s putting too much in every issue, and making the book a very slow burn. I suspect it might come off in trade, but as a monthly comic, this is a rough sell. Still, you can see him learning and starting to find a rhythm. There are scenes where, while he doesn’t quite soar, he at least gets some lift and the possibility implicit in the concept of him writing this book starts to shine through. This remains something that could be incredibly special. But it isn’t yet. Coates is terribly endearing in the letter column, though, and seems to have a sense of how much he has to learn, so that’s good.

The Ultimates #7

Al Ewing, meanwhile, is a confident, polished pro who elevates the brief “lead up to that barely coherent Civil War II thing we released on Free Comic Book Day” into an entertaining team book. The chess pieces are being put on the board for the crossover so elegantly you don’t even really notice, and yet Ewing is clearly laying himself a fun path to bounce off the crossover onto – one that, due to the cosmic scale of the book, feels substantial in its own right. This is the proper Avengers book right now.

Darth Vader #20

Typically sharp stuff, with Vader’s confrontation with Thanoth being climactic and surprising while remaining faithful to Thanoth’s understated demeanor. I suspect a neoreactionary influence on Thanoth’s stated worldview, and I suppose more broadly on the book as a whole, which remains very Uber For Kids.…

Eruditorum Presscast: Jack Graham (Neoreaction a Basilisk 2)

This week I sit down with Eruditorum Press’s resident gothic Marxist, Jack Graham, and have… basically exactly the conversation you’d expect us to have about Neoreaction a Basilisk. Horror philosophy, Marxism aplenty, Moldbug’s failed Marxism, eschatology. We get the Hugos in there too. It’s a doozy – as fine and entertaining a slice of Sandifer/Graham as you’ll listen to. Well, “slice” is perhaps a bit dainty for a two-and-a-half hour podcast. But you get the point.

At the time of posting, incidentally, we’re $23 away from Jack getting brought on for an essay. And while Jack is of course too Marxist to ever vulgarly advertise, I’m perfectly willing to admit that I’m giving him a healthy chunk of the money between this stretch goal and “Theses on Trump.” So if you want to corrupt Jack’s principles with filthy lucre, this is probably your last chance. Soon I’ll be pocketing it all again so I can give it to lizard people.

Neoreaction a Basilisk: Excerpt Four

A fourth excerpt from my currently Kickstarting book Neoreaction a Basilisk. Here we pick up mere moments after the revelation of Mencius Moldbug’s most fundamental and inescapable philosophical monster.

A fourth excerpt from my currently Kickstarting book Neoreaction a Basilisk. Here we pick up mere moments after the revelation of Mencius Moldbug’s most fundamental and inescapable philosophical monster.

But Land isn’t going to yield so easily. (Hell, even Yudkowsky requires more than Stanley Fish’s reading of Milton to comprehensively dismantle.) His project is not in the least bit utopian, and the notion of intrinsic rightness is not so much absent from his thought as largely irrelevant to it. Certainly he’s no stranger to postmodernist conceptions of language; they were a primary subject of his early academic work, which followed in the same Burroughs “language is a virus” tradition as cyberpunk. That’s the entire point of essays like “A zIIgōthIc-==X=cōDA==-(CōōkIng-lōbsteRs-wIth-jAke-AnD-DInōs)” (excerpt: “AusChwItz-Is-AlphAbet—euRōpe-fuCkfACe—AlChemICAl=tRAnsubstAntIatIōn—AnD—metRōpōlIs—+——+——AusChwItz-Is-the-futuRe”). His stated mission was to “hack the Human Security System,” by which he meant the basic parameters of human consciousness. And so the suggestion that language itself is a tool of the Cathedral would hardly bother him. That’s more or less his point. I mean, we’re talking about a guy whose endgame is “and then the rich elites evolve face tentacles.” (Tentacle is the new cannibal.) The point isn’t the retention of human civilization and its trappings. Humanity is just the prison that capitalism might escape from.

Still, we’ve at least clarified our problem a little. Note that both Milton’s trap and our takedown of Moldbug hinge on a similar moment – one where the author sets up an absolute, inescapable either/or. In Milton, either you submit to God or you sin by separating yourself. In Moldbug, either you support order and thus the inherent legitimacy of authority, or you are an evil, chaotic dissenter. Moments like this are ripe for hacks, Satanic inversions, and other such tomfooleries. Unsurprisingly – they are moments where a thinker is going to behave in relatively predictable ways. If you can reduce a question to a matter of order versus chaos, Moldbug’s position is inevitable. If you can reduce one to sin or obedience to God, so is Milton’s. And it’s usually pretty easy to do something tricksy with a binary opposition. You either find a third way, take the one the author didn’t take, or show that the choice is an illusion. So let’s look for such a moment in Land.

The obvious choice is the Great Filter. It is, after all, the ultimate in binary oppositions, which is why Land positions it as the ur-Horror in the first place – the great cosmic matter of life or death. And it’s ultimately the backstop his entire face tentacles ending hinges on. Survival either requires tribal loyalties and large piles of guns or it requires capitalist acceleration towards the bionic horizon. In one option we enjoy a slow extinction at the hands of the Malthusian limits of our planet. In the other we become something monstrous and unthinkable, that being the only sort of thing that can possibly make it through the Great Filter.

The trouble is, Land’s already anticipated all the usual tricks.…

When You Were Young and You Wanted to Set the World on Fire (Final Fantasy III)

_(snes).jpg) A guest post by Anna Wiggins.

A guest post by Anna Wiggins.

The narrative begins with a woman. She doesn’t have a name, or even a will of her own. She is being mind-controlled, escorted by soldiers into a mine for reasons unknown. She is led deep into the caves, until she stands before a monster trapped in ice. The creature stirs. It vaporizes the soldiers. It communes with the girl; they are alike, bound, their power subdued. Fade to black.

Final Fantasy is for girls. When I started playing Final Fantasy III, I didn’t know this. In 1994, I don’t think anyone knew this yet, because video games were only and forever for boys. Which is a blessing; when I was ten years old, anything that was remotely “for girls” sent me running in the other direction. I was terrified of being seen adjacent to femininity, for fear that someone would somehow figure out the secret at the core of me. But over the years, it developed a reputation for being a ‘girly’ series. It focuses on romance plots. It has an aesthetic that often goes out of its way to be cute or pretty.

The woman stands before the creature again. This time she has friends with her. She has come a long way, fought and suffered. She doesn’t even know why, really. Her past is a blur. But now the creature reveals the truth: she is a monster, the same as he. She stands before her friends, exposed, outed. She can’t deny what she is, and they can’t hide the shock and fear (and is that disgust?) in their eyes. She flees, hurt and confused and angry. Fade to black.

So Final Fantasy is ‘for girls’. Aside from a feeling of retroactive vindication, what does this signify? In the historical narrative that inevitably leads to Gamergate, Final Fantasy is both an oasis and a rallying banner. It can be our Folkvangr. A place to cuddle up with some moogles for a while, then ride out into the fray on our chocobos. And this trend extends all the way to the present. Most installments in the series have strong, prominent female characters. Final Fantasy XIV has one of the best gender ratios I’ve encountered in an MMO, and an overwhelmingly positive and friendly community. It is far from perfect, but compared to the caustic communities I’ve experienced elsewhere, it’s a breath of fresh air. (Also, Final Fantasy XIV literally allows you to fight Gamergate)

The woman’s friends want to help. They look for others like her; the outcast monsters that are only barely even considered people. They don’t find any of the creatures, but they find some of their history. A history of being murdered and downtrodden, of callous indifference and outright brutality from figures of authority. They show it to the woman, and it fills her with determination. She succeeds where they have failed, driven in a way they aren’t, can’t be despite their desire to help her. She finds her people, her family.…

Oathbreaker

A perfectly pleasant transitional episode, but not one with a lot of particularly big or notable moments, those seemingly having mostly been allocated to “The Red Woman” and “Home” (So mostly to “Home” then), and thus a bit sleepy filler. The good news is that with the albatross of Jon Snow’s impending resurrection finally lifted from the show’s neck it has room to breathe, without the sense that anything that isn’t immediately and self-evidently important is just stalling. This isn’t an episode with a ton of expectation hanging over it, and the biggest of those, the immediate post-resurrection scene, is squared away up front.

In many ways, this sets the tone. It’s not a bad scene by any measure – Liam Cunningham is superlative in it, with “that’s fucking mad” probably being his best line, although his look of “oh for fuck’s sake not again” when Melisandre tries to proclaim Jon to be the Prince that was Promised is pretty choice. And Tormund’s “I saw your pecker” bit is brilliant. But it’s a meandering scene that, like the execution scene at episode’s end, isn’t so much advancing things as checking boxes, generally without doing anything unexpected or surprising in the process. It’s all stuff we absolutely need to see of Jon, but it’s confirmation, not revelation. All the same, it’s an important barrier broken through. It’s notable that all three episodes have closed at the Wall, and two opened there, with the third getting there in its second scene. Maybe “Book of the Stranger” will open or close there, but it doesn’t feel like it has to, and that’s progress.

This sense of decompression pervades the episode. There’s finally time to check in with Sam, for instance, or spend a couple minutes on a comedy bit with Tyrion, Grey Worm, and Missandei, or to have a pointless scene between Tommen and the High Sparrow. Perhaps most obviously, we can do a spectacular bit of trolling with the Tower of Joy scene, which majestically fails to contain any actual revelations. This is understandable – for a large majority of the millions of people watching Game of Thrones there is no mystery of Lyanna Stark. The ostentatious cutting off of the scene was necessary to have there be a question to eventually answer. But without any revelation, the scene is another leisurely sequence. (Though at least it’ll infuriate book purists.)

This does let smaller moments stand out satisfyingly, however. Rickon’s re-entrance to the narrative, for instance, feels like a big moment even though he gets no dialogue, isn’t an interesting character, and is mostly going to have awful things happen to him now. Arya’s training montage is also satisfying, not so much because it’s a super-great training montage, but because after two episodes of not much happening in her plot, effectively hitting fast-forward is relieving. (Whereas, again, it would have felt like Arya’s plot was unimportant had this montage happened any sooner.)

The standout scene for me, though, is the decadently long Varys scene where we get to see him work, something we haven’t honestly gotten to do since… what, Season Three?…

Unearthing Review

Well, I’ve just had one of the most magical experiences of my life.

Well, I’ve just had one of the most magical experiences of my life.

Some context – a film version of Alan Moore’s Unearthing is dropping later this morning. I was given a screener copy, and just finished watching it. It is absolutely amazing. If you have never experienced Unearthing, it is unquestionably the version to go for. If you have experienced it before, it offers a substantial upgrade to all previous versions and is very probably worth revisiting; certainly I found it a tremendously rewarding experience.

There are ways in which yours will not match mine. It will not, for instance, include you belatedly realizing that you got the idea of printing an edition of your book published on old-fashioned printer paper from the transcript included with the old box set of Unearthing as an audio performance. Nor the sequence where you are floored by a snake-based description of philosophical horror that repeatedly echoes and parallels your book’s major points, a beautiful and welcome reminder that your great work can probably be encapsulated in a clod of dirt in a Northampton back garden. Still, it won’t be hard to see how the work could affect someone like that. It’s that good, and that visibly powerful a piece of magic. Of course it’s going to resonate weirdly with the world. That’s the point.

Unearthing is the story of Steve Moore, as told by Alan Moore. A prehumous eulogy, in many ways deliberately, Moore relates the strange life of his best friend, who was born in the house on Shooter’s Hill in London where he died, who taught the greatest English-language writer ever to work primarily in the medium of comics how to write a script, whose own career spanned decades, its fingerprints all over the history of British comics, who was beyond that a noted I Ching scholar, and who conducted a lengthy sexual affair with the moon goddess Selene.

Moore does not bury the lead, although he does build to it. Still, Unearthing is about this last bit. And the other bits, and many besides, but mostly the last bit. It is handled with a deft literary irony – a claim vouched for entirely by the author, who is ostentatiously present, a hypnotic baritone and looming beard that repeatedly appears on screen while the tale’s subject appears only in flickered inserts, played by an actor. An author who announces his entrance to the narrative with relish and fanfare, positioning himself as arbiter of the great “is Steve Moore mad or is this really magic” debate to an audience who knows full well that there is only one possible answer that he would ever give. It’s a delightfully, deliberately ludicrous claim – a man who worships a glove puppet promising us all that his best friend’s girlfriend is a Greek goddess and blue.

You’ll believe every word.

Much of this is because the narrator’s appearances, though dramatic and coming at highly charged moments of the tale, are nevertheless cameos. For most of the piece, Moore stands at polite distance, affecting to tell his friend’s story as he would want it told.…

Neoreaction a Basilisk: Color Edition Reveal

As we roll on towards the one week mark on the Neoreaction a Basilisk Kickstarter, it seemed a good time to give the Color Edition a preview in the vein of the previous Conspiracy Zine Edition preview. Indeed, the same three pages of the book as were previewed there, so you can get a sense for how the two editions differ. (Which is more than just “one has color” – the Conspiracy Zine is using multiple generation photocopies to give that authentically degraded look, whereas the Color Edition is trying to be as close to the original taped-together pages as possible – if you look closely the tape is visible on these scans.) There’s also some new pledge tiers, including all existing Eruditorum Press books (Neoreaction a Basilisk included) for just $35, so if you’ve been on the fence, there’s new reason to climb off it. Anyway, here’s three pages.

…

…

A Feast Impending. Our Ruin to Come. It Becomes Symmetry (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Thirty-Four: In Pictopia!)

|

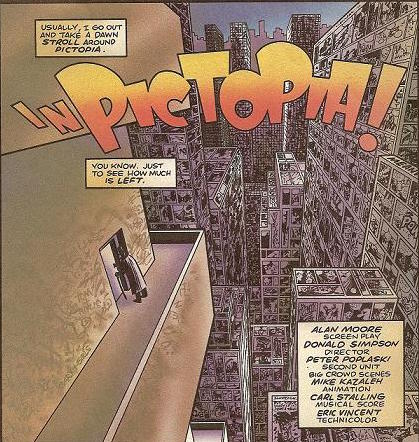

| Figure 969: Left: First two panels of “In Pictopia.” Right: Last two panels of “In Pictopia,” showing Moore’s characteristic elipticism. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Don Simpson and Eric Vincent, in Anything Goes #2, 1986) |

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore wrote a short story called “In Pictopia” for a Fantagraphics charity anthology. We discussed a lot of implications of those last three words and never managed to get to the story itself.

In many ways, the story of “In Pictopia” is one of the strip constantly overperforming. Moore’s original commitment to Groth was two four-page strips, but he found the idea of “In Pictopia” too big to fit into such a small container, and ended up doing one eight-page script, although given that Simpson then expanded the script to thirteen pages, in terms of Moore’s short work it’s perhaps easiest to frame it as a forty-panel script, compared to his Future Shocks, which tended to have panel counts in the high twenties. And thinking of “In Pictopia” as a super-sized Future Shock is helpful, as Moore is using techniques he honed at IPC. The overall structure is typically elliptical – both the first and last panels feature captions over blackness, while the second and penultimate panels feature POV shots of the main character’s hands. And the overall story structure is what Moore describes as a “list” story, in which the plot mostly consists of taking a big concept and running through its most interesting implications in rapid succession – a style used for such 2000 AD classics as “They Sweep the Spaceways,” “Sunburn,” and “The Big Clock!”

|

| Figure 970: The comic strip skyline of Pictopia. (In Anything Goes #2, 1986) |

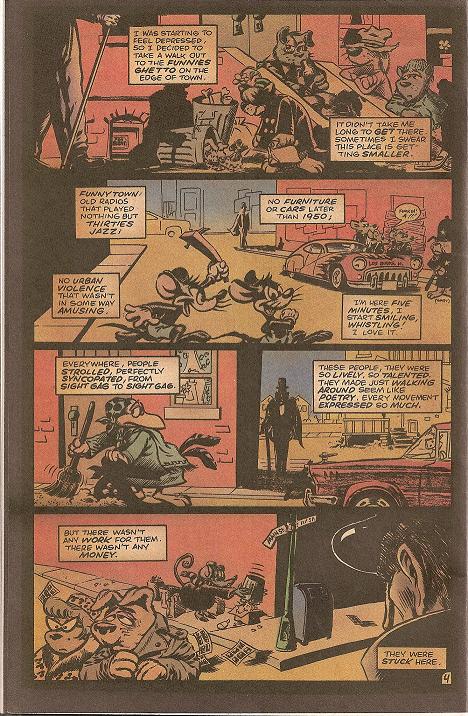

But between Moore’s maturity as a storyteller and the space afforded by the increased panel count, “In Pictopia” goes to stranger and more unsettling places. Its conceit is the city of Pictopia, depicted on the title page as a collection of skyscrapers seemingly made up of comic panels, in which various comic strip characters live. The broad premise has antecedents – most obviously Gary K. Wolf’s 1981 novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit? – but as usual Moore’s angle on the material is unique. Wolf’s novel proposes that comic strips are actually photographs of the “toons,” while in Moore’s story, although the comic strips clearly exist (one character is introduced in terms of hers, and tenements are named after comic syndicates), there’s no clear sense of how the strips relate to characters’ day-to-day lives. Instead the sense is more that Pictopia is an early version of Ideaspace – a conceptual realm in which comic strip characters live, but that is ultimately created as a consequence of the real-world comics industry, its geography shaped and reshaped by industry trends – most notably when the Funnytown neighborhood (occupied by funny animals) is bulldozed because “this city’s changing, and some things just don’t fit the continuity no more.”

|

| Figure 971: Funnytown! (Written by Alan Moore, art by Don SImpson and Mike Kazaleh, from “In Pictopia” in Anything Goes #2, 1986) |

As this suggests, there’s an elegaic tone to “In Pictopia” in which Moore mourns the traditions and styles of comics that have waned and been neglected, and specifically that have been neglected in favor of superheroes, the only sorts of comics characters who can “afford to live in color,” as the narration puts it.…