A Brief Treatise on the Rules of Thrones 3.07: The Bear and the Maiden Fair

|

| It was a hairy bear. It was a scary bear. Brienne and Jaime beat a hasty retreat from its lair, and described it with adjectives. |

State of Play

The choir goes off. The board is laid out thusly:

Lions of King’s Landing: Tyrion Lannister, the Hand of the King Tywin Lannister

Lions of Harrenhal: Jaime Lannister

Dragons of Yunkai: Daenerys Targaryen

Direwolves of the Wall: Jon Snow

Direwolves of Riverrun: Robb Stark, Catelyn Stark

Bears of Yunkai: Jorah Mormont

Roses of King’s Landing: Margaery Tyrell

Burning Hearts of King’s Landing: Melisandre

The Direwolf, Bran Stark

The Direwolf, Arya Stark

Direwolves of King’s Landing: Sansa Stark

The Kraken, Theon Greyjoy

Tigers of Riverrun: Talisa Stark

Stags of King’s Landing: King Joffrey Baratheon, Gendry

Flowers of King’s Landing: Shae

Bows of the Wall: Ygritte

Chains of King’s Landing: Bronn

The Dogs, Sandor Clegane

The episode is in twelve parts. The first part runs two minutes and is set on the far side of the Wall. The first image is of the open sky.

The second runs four minutes and is set in the Stark camp between Riverrun and the Twins. The transition is by family, from Jon Snow to Robb Stark.

The third runs two minutes and is set in the woods beneath the Wall. The transition is by family, from Robb Stark to Jon Snow.

The fourth runs eight minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by family, from Jon Snow to Sansa Stark.

The fifth runs seven minutes and is set outside Yunkai. The transition is by dialogue, from Joffrey and Tywin talking about Daenerys to her.

The seventh runs four minutes and is in sections; it is set in King’s Landing. The first section is three minutes long; the transition is by hard cut, from Daenerys stroking Drogon to Shae looking at her golden chains. The second section is one minute long; the transition is by dialogue, from Tyrion saying he would take care of his bastards to Gendry.

The eighth part runs two minutes and is set in the Riverlands. The transition is by dialogue, from Mellisandre to Arya talking about her with Thoros and Berric.

The ninth runs three minutes and is set in Harrenhal. The transition is by region, remaining in the Riverlands.

The tenth runs five minutes and is set in the Dreadfort. The transition is by family, from Roose Bolton to Ramsey Snow.

The eleventh runs eight minutes and is set in the North along the Wall. The transition is by hard cut, from Theon about to have his cock cut off to Jon and Ygritte. The second section is 44:30; the transition is by family, from Jon Snow to Bran Stark.

The twelfth runs eight minutes and is set in the Riverlands south of Harrenhal. The transition is by hard cut, from Osha to horses standing on a hill. The final shot is of Jaime and Brienne walking out of Harrenhal having prevented a bear from completing a Full Web.

Analysis

The phenomenon of Martin writing for Game of Thrones is reliably interesting.…

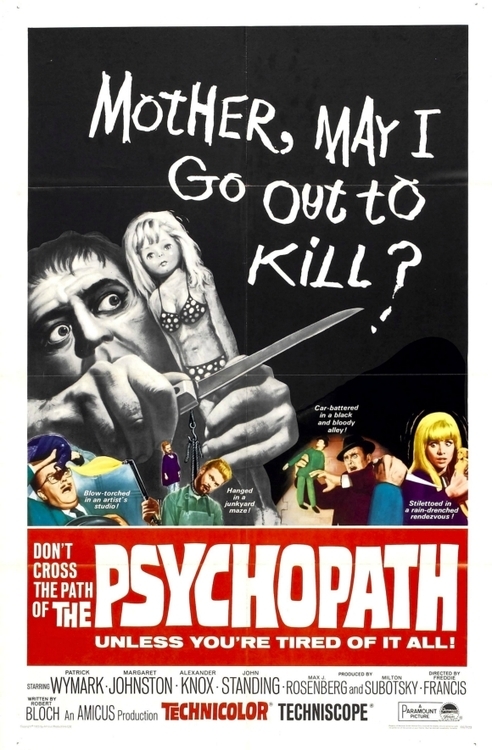

Eruditorum Press is thrilled to announce the return of Holy Boson and the City of the Dead podcast to our… whatever you call airwaves for a podcast. Anyway, this is the famed “lost film” of the Amicus set, with a story that I know Holly related to me once, but that I’ve completely forgotten the details of. I’m sure she explains it in the podcast. Anyway, with a script by legendary horror writer Robert Bloch, one assumes this is potentially a hidden gem. Or possibly a legendary trainwreck.

Eruditorum Press is thrilled to announce the return of Holy Boson and the City of the Dead podcast to our… whatever you call airwaves for a podcast. Anyway, this is the famed “lost film” of the Amicus set, with a story that I know Holly related to me once, but that I’ve completely forgotten the details of. I’m sure she explains it in the podcast. Anyway, with a script by legendary horror writer Robert Bloch, one assumes this is potentially a hidden gem. Or possibly a legendary trainwreck.

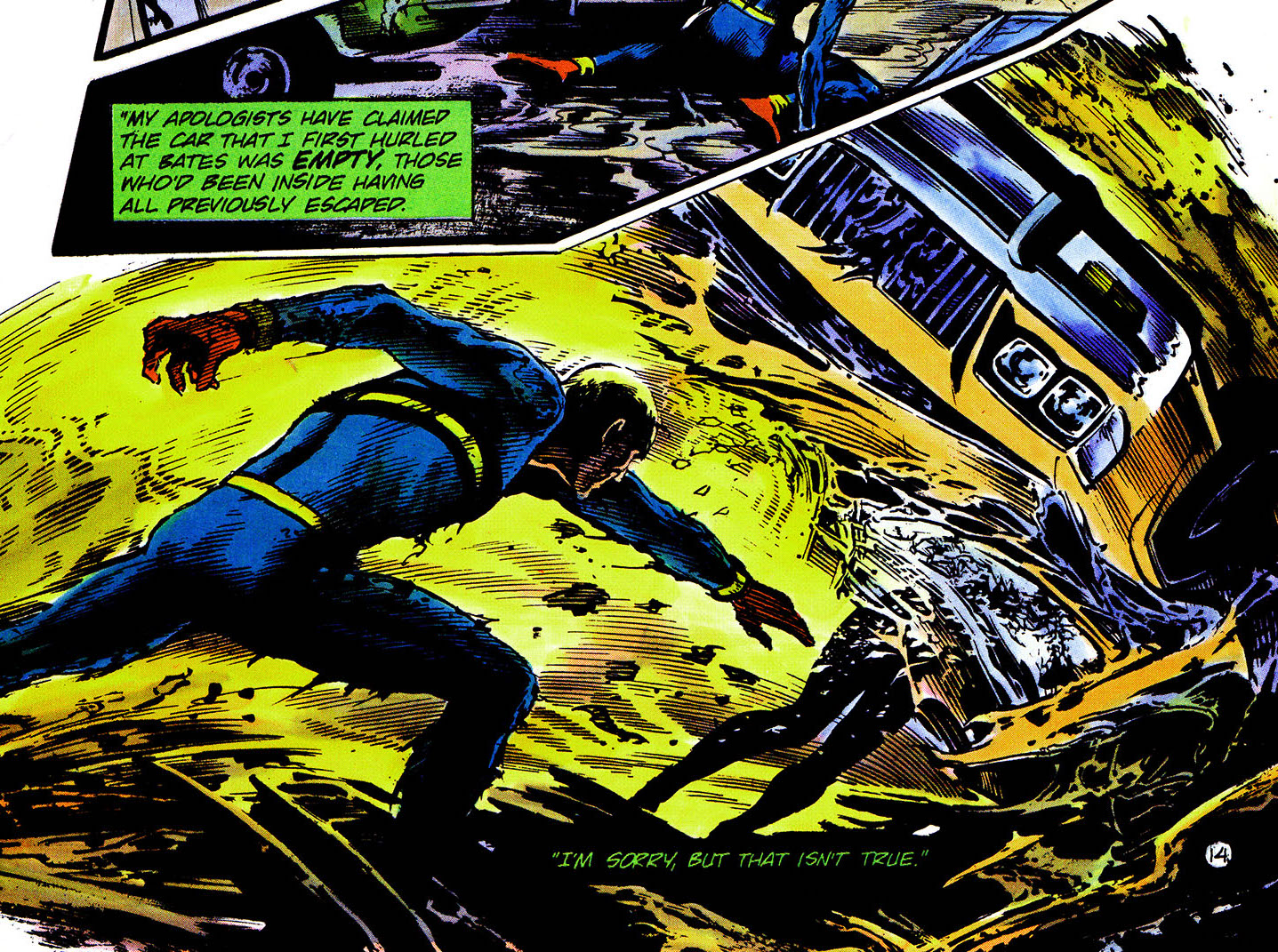

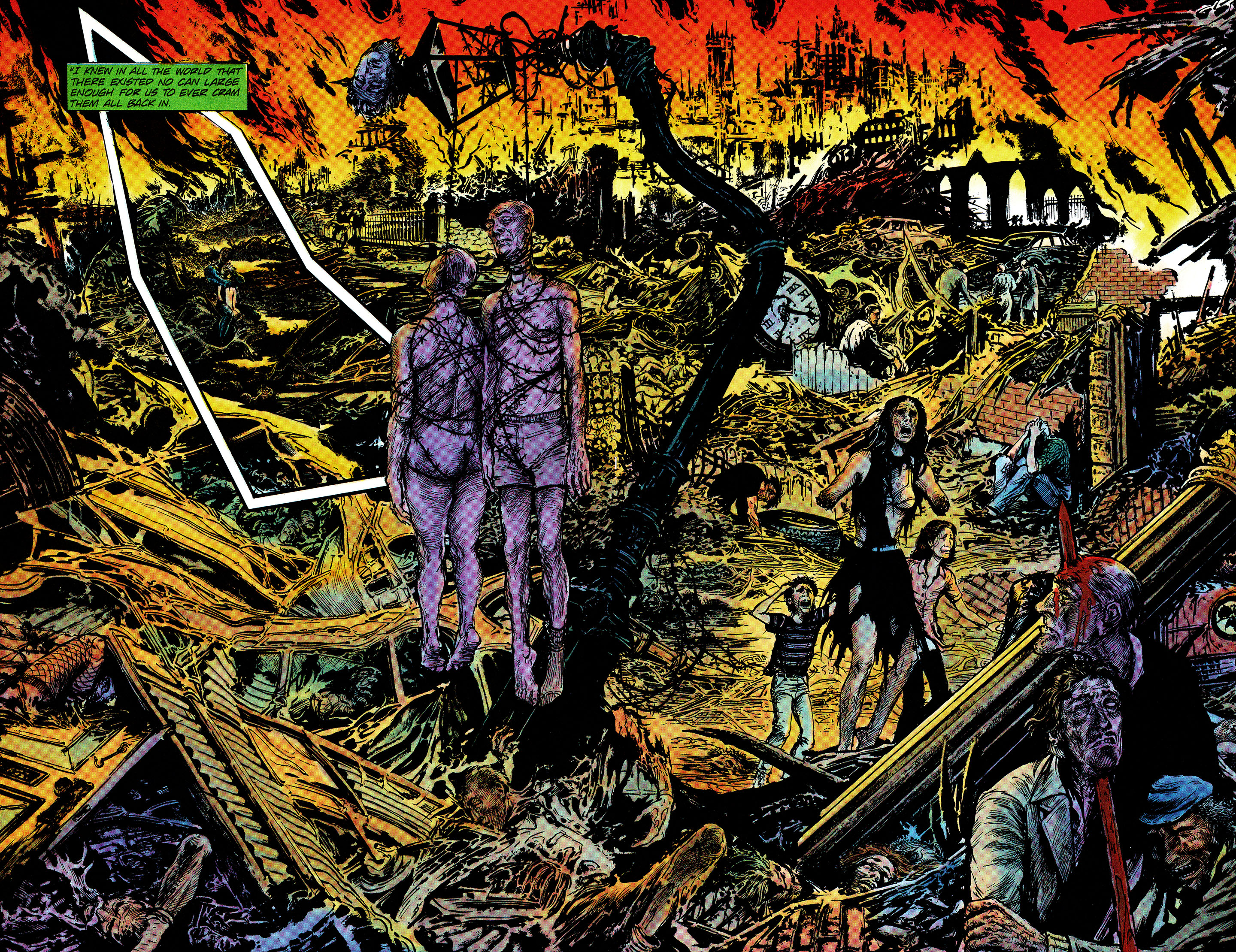

And so begins the last month of the long and terrible WicDiv hiatus.

And so begins the last month of the long and terrible WicDiv hiatus.

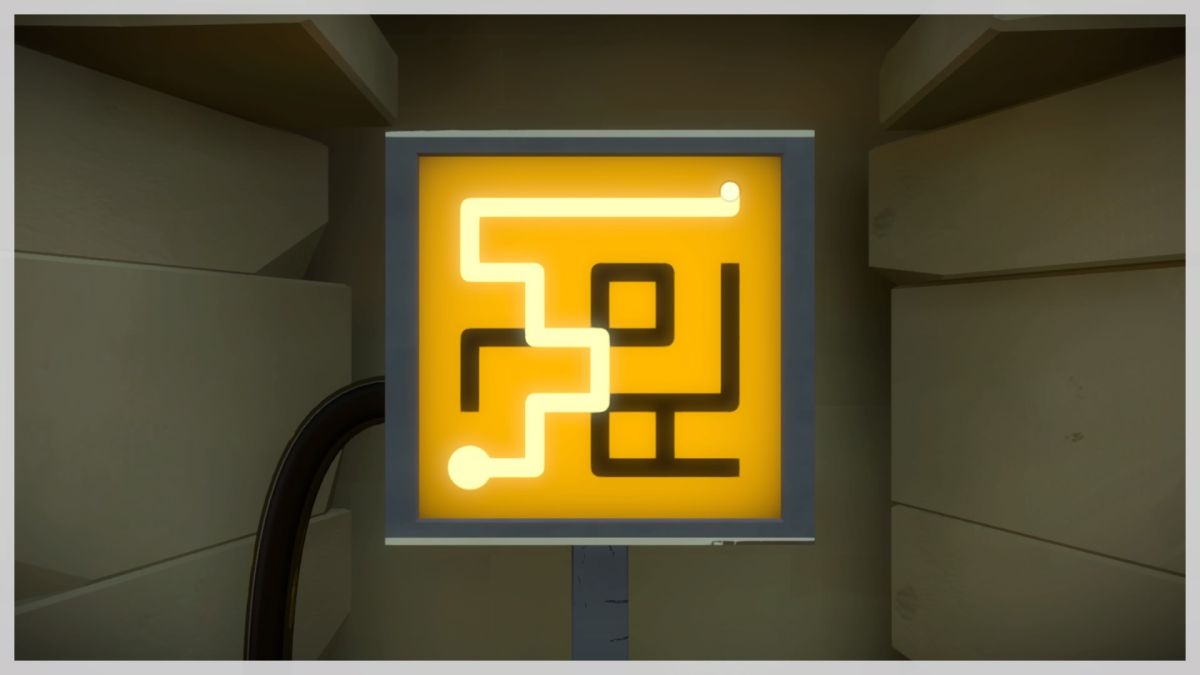

I found myself weirdly fascinated in hindsight by the early reviews of

I found myself weirdly fascinated in hindsight by the early reviews of  Let me start by making something as clear as I possibly can.

Let me start by making something as clear as I possibly can. Jack, as news of Umberto Eco’s death was breaking last night, Tweeted

Jack, as news of Umberto Eco’s death was breaking last night, Tweeted