Comics Reviews (November 18th, 2015)

Vader Down #1

Vader Down #1

It’s a good week when this is the sort of thing occupying the bottom slot of my list, because there’s almost nothing wrong with it. You can, perhaps, tell that Aaron is better suited to his characters than Gillen’s – his dialogue for Aphra and company feels like a hollow imitation of the characters. But that’s a minor detail in a comic that giddily makes Vader seem tremendously powerful and tremendously fucked all at once. Good fun, and hard to imagine a Star Wars fan that isn’t going to be loving this.

The New Avengers #3

I love the pentacled Cthulhu villain that is Moridun. And the three-scenes-in-one banter at the start. And Power Man deciding to call out Wiccan on his name. And really most of this. And I’m fascinated by POD, a character I’m not actually sure I’ve registered as a thing before, but who is without a doubt the most interesting part of this issue. Good stuff; I think this is the current best of the Avengers books.

Ms. Marvel #1

Ms. Marvel punches gentrification. It’s as awesome as you’d hope from that description. The “artisinal sushi” line is probably my favorite of the week, and the backup story by Alphona is genuinely charming. Mike looks like a great character, and I can’t wait to see what Wilson ends up doing with her. While I definitely prefer Alphona’s art to Miyazawa’s, this series is clearly in wonderful hands as ever.

Phonogram: The Immaterial Girl #4

Gloriously out of left field, Phonogram swerves away from all of its apparent plots, connecting back to them only fleetingly and midway through, in an issue that’s mostly black and white for good measure. It’s the sort of thing that makes you genuinely surprised that we’re officially Done With Phonogram in two issues time, as it gestures to just how much there is to do with this world and these characters. How will this tie back in? Will it tie back in? What the fuck is Gillen doing? I have no idea, but I’m wholly confident it’s brilliant, so whatever. “I liked Claire Danes’s earlier, more difficult material” is definitely the second funniest line of the week though.…

This is an essay from my forthcoming collection Guided by the Beauty of Their Weapons: Notes on Science Fiction and Culture in the Year of Angry Dogs, out on December 27th, and

This is an essay from my forthcoming collection Guided by the Beauty of Their Weapons: Notes on Science Fiction and Culture in the Year of Angry Dogs, out on December 27th, and .jpg) We’re pleased to announce the release of Pex Lives 27, in which James and Kevin are joined by, and I quote their episode description here, “the very clever and lovely Eliot Chapman to discuss The Invasion.”

We’re pleased to announce the release of Pex Lives 27, in which James and Kevin are joined by, and I quote their episode description here, “the very clever and lovely Eliot Chapman to discuss The Invasion.” This is solidly Gatiss’s best-ever

This is solidly Gatiss’s best-ever  There is a moment in the first episode of

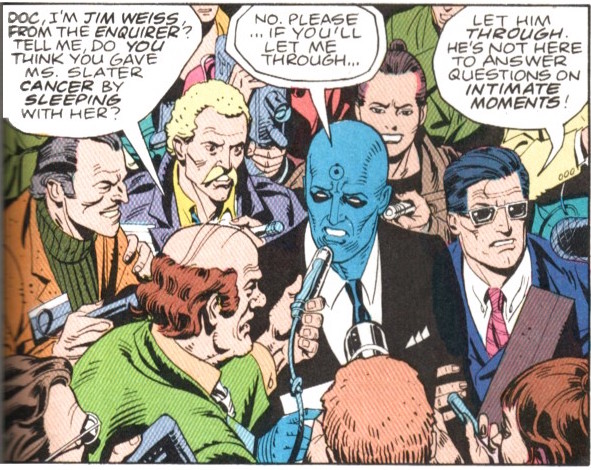

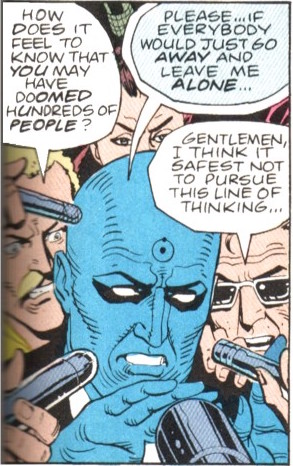

There is a moment in the first episode of  But there’s one name, of course, that’s conspicuously absent from the reactions: Moore’s. This is unsurprising; unlike Chaykin, Moore had no problem taking it personally, in no small part because it blatantly was personal. Geppi’s attack on the loose morals of American comics was specifically aimed at Moore, and blatantly accused him of corrupting the youth of America. And DC had given into the attacks without blinking an eye, then spent months dissembling about it in the face of his protests while, in his view, trying to threaten him into coming back to work for them. Indeed, in his largest single piece on the controversy, an editorial in the February 13

But there’s one name, of course, that’s conspicuously absent from the reactions: Moore’s. This is unsurprising; unlike Chaykin, Moore had no problem taking it personally, in no small part because it blatantly was personal. Geppi’s attack on the loose morals of American comics was specifically aimed at Moore, and blatantly accused him of corrupting the youth of America. And DC had given into the attacks without blinking an eye, then spent months dissembling about it in the face of his protests while, in his view, trying to threaten him into coming back to work for them. Indeed, in his largest single piece on the controversy, an editorial in the February 13 Given that these were the terms on which he viewed the debate, it’s hardly a surprise that he saw its resolution differently. This carried some risk, as Moore put it, of him “looking like a shrill, over-reactive prima donna,” and certainly that was what DC sought to quietly paint him as, calmly explaining that, as Dick Giordano put it, the ratings system was not “a moral issue at all. It was essentially a business issue,” and complaining that “there was no way I could respond to people who were becoming so emotional about what seemed to me a very simple marketing device.”…

Given that these were the terms on which he viewed the debate, it’s hardly a surprise that he saw its resolution differently. This carried some risk, as Moore put it, of him “looking like a shrill, over-reactive prima donna,” and certainly that was what DC sought to quietly paint him as, calmly explaining that, as Dick Giordano put it, the ratings system was not “a moral issue at all. It was essentially a business issue,” and complaining that “there was no way I could respond to people who were becoming so emotional about what seemed to me a very simple marketing device.”… This week I’m joined by Gene Mays of the superlative

This week I’m joined by Gene Mays of the superlative  Secret Wars #7

Secret Wars #7 On September 13th, 1993, exactly four days after my eleventh birthday, the world slipped forever from my grasp. As with anyone for whom this happens, my reaction at the time was little more than a vague annoyance and sense of disapproval. I really never played

On September 13th, 1993, exactly four days after my eleventh birthday, the world slipped forever from my grasp. As with anyone for whom this happens, my reaction at the time was little more than a vague annoyance and sense of disapproval. I really never played  Holy shit that was good. An astonishingly well-tuned, clever piece of television full of surprises big and small. Every bit as good as you would hope from the writing credit, from the actors, from the directors, and really from Doctor Who. I am as thrilled to have watched this happen as I am jealous of those who got to see Terror of the Zygons on first transmission, and I have zero doubt that in 2055 fandom will talk about this like we talk about Terror today.

Holy shit that was good. An astonishingly well-tuned, clever piece of television full of surprises big and small. Every bit as good as you would hope from the writing credit, from the actors, from the directors, and really from Doctor Who. I am as thrilled to have watched this happen as I am jealous of those who got to see Terror of the Zygons on first transmission, and I have zero doubt that in 2055 fandom will talk about this like we talk about Terror today.