Tricky Dicky, Part 8: Margaret on the Escalator

In Richard III, the deposed former queen, Margaret, widow of Henry VI, though notionally banished, continues to haunt the new Yorkist regime of Edward IV. She has no role anymore, no status. (In most theatre productions she literally has no role – she is cut from the play for time reasons). She is a defeated enemy. An enemy, moreover, who is directly responsible for the death of the new Yorkist king’s father. Even so, the Yorkists are content to let this relic of the defeated Lancastrians carry on perambulating around the court, snarling at them, cursing them, and wailing of her unjust plight at their hands. They occasionally grumble that she should be gotten rid of, but nobody does anything about it. Not even openly taunting and cursing the new queen, her replacement, can earn Margaret more than a verbal rebuke. Margaret haunts the outskirts of the play like a bad conscience, the bad conscience of all the other characters. That’s certainly how she thinks of herself: as a living rebuke to those whose triumph is also her desolation. And it’s hard not to think that they see her that way too, despite the fact that she has plenty to have a bad conscience about herself, as they remind her.

Margaret is one of the largest and important roles in all of Shakespeare, and is also one of the most neglected. (She is undergoing rediscovery these days, partly thanks to Sophie Okenado’s portrayal of her on TV in the second series of The Hollow Crown.) She is clearly one of the most crucial characters in the entire First Tetralogy. She is a major character in the middle two plays, an important minor character in the first, and an absolutely vital thematic presence haunting the last – the one from which she is usually excised! Through the cycle she goes from being the young (virtually kidnapped and bartered) foreign bride of the English king, to being the fiercest warleader of the Lancastrians in their battle against the house of York, to being Lancaster’s defeated and bereaved last remnant. She is capable of extreme cruelty, ruthlessness, and spite, but also sympathetic as a woman essentially fending for herself against the entire tide of history as it smashes her world to pieces. She is one of young Shakespeare’s major triumphs as a dramatist, and (these days) clearly one of the great theatre roles for women. She is both victim and villain, winner and loser, young and old, powerful and helpless. And yet she is virtually forgotten. In a perverse way, this is apt, since she is, to her core, a paradoxical, contradictory, liminal presence. And she is a tragic heroine. Fintan O’Toole, in a wonderful book called Shakespeare is Hard, But So Is Life, says that Othello is as much Iago’s tragedy as it is Othello’s. There is no requirement that a tragic hero be morally perfect, or even good on balance. Look at Macbeth. Like him, Margaret is deeply ambiguous.…

The following review is a guest post by Eye-Patch, a reviewer and columnist for one of the most respected arts and culture magazines in the Terran Federation. In addition to his writing, Eye-Patch is a veteran, teacher and citizen.

The following review is a guest post by Eye-Patch, a reviewer and columnist for one of the most respected arts and culture magazines in the Terran Federation. In addition to his writing, Eye-Patch is a veteran, teacher and citizen. Hello again, my fellow muggles.

Hello again, my fellow muggles.  And

And  It’s Shabcast listenin’ time again.

It’s Shabcast listenin’ time again.  Stories belong to all of us. Sounds like a trite, sentimental truism, doesn’t it? So let’s add a vital corollary: Because we make them.

Stories belong to all of us. Sounds like a trite, sentimental truism, doesn’t it? So let’s add a vital corollary: Because we make them.  Yes, I use the Oxford comma. I use it because it is sensible, stylish, and clarifying.

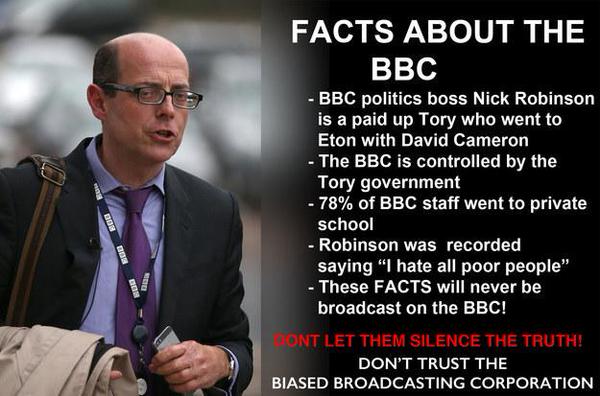

Yes, I use the Oxford comma. I use it because it is sensible, stylish, and clarifying. Please find attached the latest Shabcast. It’s the first part of another long chat between myself and Daniel. In this episode we talk about the 2006 Mike Judge movie Idiocracy, which is ‘relevant’ nowadays as loads of people have jumped to the wrong conclusions about the Trump phenomenon and clambered aboard the everyone’s-an-idiot-nowadays-except-me bandwagon, using Idiocracy as a cultural touchstone. (Seriously, google the phrase ‘Trump Idiocracy’ and behold the avalanche of sneering, purblind, elitest drivel.) Daniel has little time for the film and isn’t shy about saying why. And nor am I.

Please find attached the latest Shabcast. It’s the first part of another long chat between myself and Daniel. In this episode we talk about the 2006 Mike Judge movie Idiocracy, which is ‘relevant’ nowadays as loads of people have jumped to the wrong conclusions about the Trump phenomenon and clambered aboard the everyone’s-an-idiot-nowadays-except-me bandwagon, using Idiocracy as a cultural touchstone. (Seriously, google the phrase ‘Trump Idiocracy’ and behold the avalanche of sneering, purblind, elitest drivel.) Daniel has little time for the film and isn’t shy about saying why. And nor am I.