Lost Exegesis (Pilot Part 1)

Hello, I’m Jane, your stewardess for the Lost Exegesis, a flight of fancy that explores the esoteric mysteries of LOST, an American TV show that ran on ABC from 2004 until 2010. It’s a show that had a significant impact on TV at the time, and still does to an extent.

Hello, I’m Jane, your stewardess for the Lost Exegesis, a flight of fancy that explores the esoteric mysteries of LOST, an American TV show that ran on ABC from 2004 until 2010. It’s a show that had a significant impact on TV at the time, and still does to an extent.

But the Exegesis isn’t going to be about charting any of that, or commenting on the value of individual episodes; we’ll not be diving into fan rankings, outside critical acclaim, comments from the showrunners, or how the show fit into the televisual landscape at the time. Rather, the primary focus will be on interpreting the text regarding the show’s esoteric elements (as you might have suspected, given I’m calling this an “exegesis”) through a thorough close reading. This will include an examination of the show’s intertextuality: if Watership Down shows up in the text, we’ll take a look at Watership Down.

Every few weeks or so we’ll examine one episode from the series, in order. With 121 episodes, we’ll be at this for quite a while. There’s no rush. We might even cover what we need to cover by the end of Season One, which is only 25 hours of TV. So there’s that.

So, a note about the ground rules regarding these essays. Each one will be divided into two parts. The first part will examine the show as if we were watching it in the present tense, without reference to future episodes. In other words, no spoilers. The bottom line is, if you haven’t seen the whole show yet, you can follow along through the first half of each essay as the Exegesis unearths the buried treasures of the Island.

The second part will take a different approach – it will reexamine the episode with particular consideration for future events in the show, and testing various theories of the Exegesis along the way. It’s here that we’ll be looking at the show’s ancillary materials. This portion of each essay will begin with a picture of the standard LOST title card and a subtitle of “LOST Through the Looking Glass” to warn off anyone who doesn’t want to know what’s going to happen next.

Finally, the Comments section is not spoiler-free. Most people have already seen the show (it’s been around for quite a while now) and you’ve probably heard all about it anyways. Besides, I don’t want to be in the position of policing the comments. That said, I do ask that we try to stay focused on the episode at hand, a place to talk about the episode’s quality, other themes, whatever suits your fancy.

Okay, let’s go back!

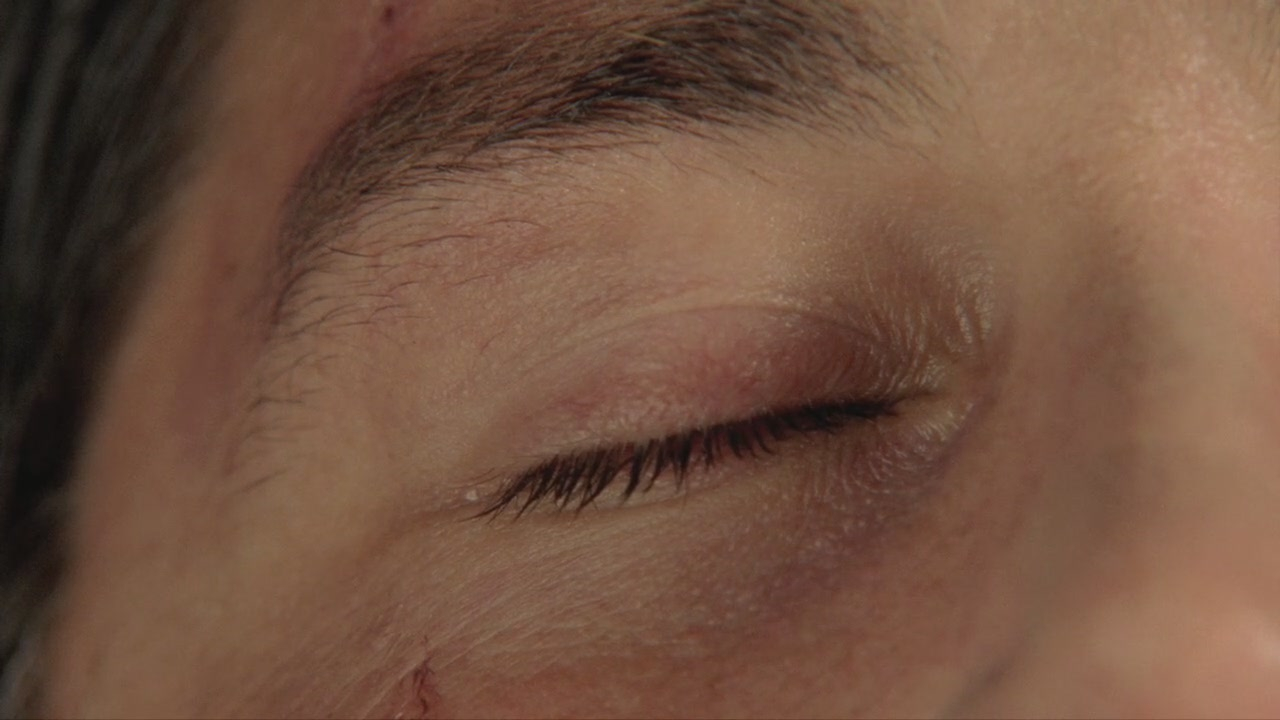

Opening Eye

LOST begins with a starkly visual image, an Opening Eye. The eye is clearly reflective – we can see the trees and sky above. A man in a suit is lies on the ground in a bamboo jungle. He’s disoriented. He looks around, and sees a dog saunter by. He gets up, wincing, and is almost puzzled to find a small bottle of liquor in his pocket. And so we are introduced to a mystery. Who is this guy? Where is he? Why does he have booze in his pocket?

So this is a show that begins in mystery, and with a rather startling image, one that’s rather significant in terms of its esoteric symbolism: the Opening Eye (especially the Right eye) signals first and foremost an Awakening. With a capital A. A combination of Perception and Identity. It’s not just waking up, but becoming aware of an Inner Truth, which is also a reflection of the Universe—in accordance with the alchemical principle of “as above, so below.” Of course, this is what esotericism is all about. It’s the kind of awakening that is easily cast in terms of “resurrection.” Which is terribly apt for someone who’s just survived a plane crash.

The second thing to note about this opening shot is the reflection in the eye, of the trees and sky above, which is repeated in the very next shot, but from Jack’s subjective position. This is what we call a “mirror-shot.” It’s especially significant given there’s an awful lot of mirroring in this episode, mostly around Jack, who has a mirror-twin in this episode.

Mirror-Twin

I supposed I should explain that term, “mirror-twin.” Literally speaking, mirror twins are twins who aren’t just duplicates of each other, but have a kind of “reversal of polarity” to them, specifically a left/right opposition that’s embedded in their genetics. For example, one will be left-handed, the other right-handed. Likewise, any asymmetry in one’s features is reversed in the other’s. To be clear, I’m using the term metaphorically here, as a structural principle. Jack is mirror-twinned with the pilot; they aren’t literally twins, mirror or otherwise.

I supposed I should explain that term, “mirror-twin.” Literally speaking, mirror twins are twins who aren’t just duplicates of each other, but have a kind of “reversal of polarity” to them, specifically a left/right opposition that’s embedded in their genetics. For example, one will be left-handed, the other right-handed. Likewise, any asymmetry in one’s features is reversed in the other’s. To be clear, I’m using the term metaphorically here, as a structural principle. Jack is mirror-twinned with the pilot; they aren’t literally twins, mirror or otherwise.

- The episode begins with Jack, and ends with the pilot.

- Jack’s right eye is an Opening Eye; the pilot’s right eye is swollen shut.

- Both Jack and the pilot have wounds on their right cheeks, and below their left eyes.

- Jack once took airplane lessons, but it wasn’t for him; the pilot took airplane lessons, and actually became a pilot.

- Jack takes responsibility for the passengers on the beach; the pilot is ostensibly responsible for the fact there are passengers on the beach.

- Jack awakens on the ground, having fallen to the earth; he sees the trees and sky above, reflected in his eye. The pilot dies having risen to the sky, up among the trees, reflected in the water below.

And this is surely intentional, or should we say self-conscious, for the title of the episode is Pilot. It’s a pilot episode. About a pilot.

The structure of the episode is likewise mirrored and twinned, with a FlashBack separating the two halves. The first half begins in light and ends in darkness. The second half begins in light and climaxes with “day becoming night” as Charlie describes it. In the first half, Jack emerges from the jungle; in the second, he heads into it. A plane crash marks the beginning of the episode; the fall of the cockpit is the climax of its second half. Both Jack and Kate countdown from five to ward off fear in each half, respectively.

Even the quest into the jungle at the end of the second half features a MacGuffin that exemplifies this most basic alchemical principle—Jack, Kate, and Charlie are in search of the airplane’s transceiver, a device which exemplifies a union of opposites, given that it is simultaneously a transmitter and a receiver.

The principle of the “union of opposites” is likewise reflected in the recurrence of the airline’s logo, etched on glass, in the interior of the plane, right in front of the cockpit. Here we see a “Circle in the Square,” an esoteric symbol from freemasonry which symbolizes the union of the Divine and the Material Body, healing the Cartesian dichotomy of “mind” and “body.”

The principle of the “union of opposites” is likewise reflected in the recurrence of the airline’s logo, etched on glass, in the interior of the plane, right in front of the cockpit. Here we see a “Circle in the Square,” an esoteric symbol from freemasonry which symbolizes the union of the Divine and the Material Body, healing the Cartesian dichotomy of “mind” and “body.”

So both in terms of its aesthetics and structure, Pilot Part 1 has at its heart a mirror-twin conceit.

Eye in the Sky

Concurrent with the opening image of an opening eye, and having everything to do with “pilots” is the fact of the crashed airplane. The Eye symbol is the airplane’s logo. Given the crashed airplane features at the beginning and end of the episode (as well providing the setting for the singular FlashBack that bifurcates its middle) it behooves us to attend to its role in the small opera, esoteric or otherwise.

Because this is an alchemical text, being examined in the context of Eruditorum Press, where alchemy’s secret is defined in relationship to material social progress, let us now consider the position of an airplane crashing on television on September 22nd, 2004. It’s barely three years since 9/11. In this context, the sight of a crashed airplane and the attendant horror is going to resonate deeply in a way that it wouldn’t had the show aired a year before that particular event. And indeed it did—when the ratings came out, showrunner Damon Lindelof got the call from the network that the show was a “monster”—LOST was an instant smash hit. No wonder: the crashing of airplanes, explosively, is going to stir up emotions of horror and fear and yet also fascination, making the airplane a potent symbol for our modern times.

Not that it wasn’t already. A great metal bird flying in the sky, with a giant eye painted on its body? Symbolically, then, the eye becomes an Eye in the sky, perhaps the Eye of Providence, suggesting an “all-seeing eye” that bespeaks not just to the resulting surveillance state of America post-9/11, but of the Divine as well. But this eye has crashed, died in the jungle on some Island in the South Pacific, according to the pilot’s testimony. If the All Seeing Eye has died, well, there are esoteric implications to that.

One implication that emerges from this meditation is the episode’s tension between the tropes of “realism” (from Jack rushing out of the jungle to save everyone, to the characters’ concerns with realistic matters: finding transceivers, stitching up wounds, performing CPR, needing appropriate footwear for tromping through the jungle) and the tropes of “myth,” specifically through the presence of a “monster” on the Island. This tension is reflected by two different works of art that are alluded to in the episode’s imagery.

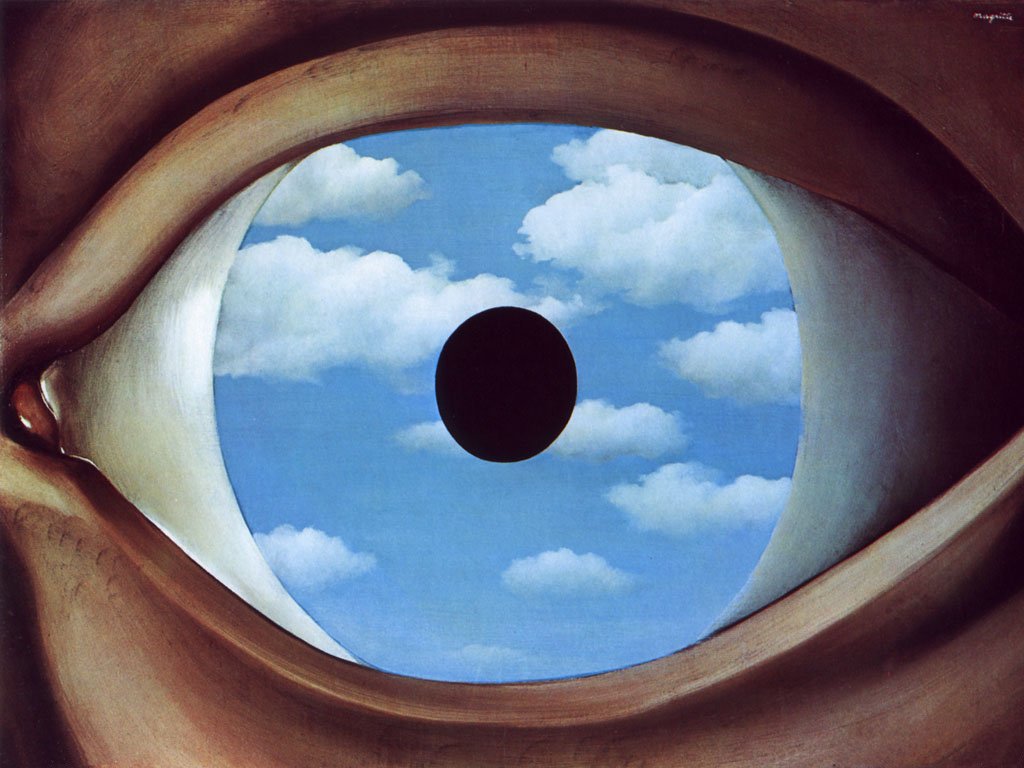

On the one hand, we have an Eye that mirrors the sky, itself mirrored by a puddle on the ground. Which rather invokes The Red and the Black, an 1830 novel by Stendhal, which is certainly an apt analogy for LOST, given the fake epigraph that heads chapter 13:

“A novel, gentlemen, is a mirror carried along a highway. Sometimes it reflects to your view the azure of the sky, sometimes the mire of the puddles in the road. And the man who carries the mirror on his back will be accused by you of immorality! His mirror shows you the mire, and you blame the mirror! Blame, rather, the road in which the puddle lies, and still more the road inspector who lets the water stagnate and the puddle form.”

Stendhal’s work falls into the realist tradition, and includes a biting satire of the French social order of the time, but it’s also one of the first “psychological” novels to be written, with great detail paid to the subjectivity and interiority of its characters. The quote is funny, because it purports a realist aesthetic of art, and yet Stendhal is really quite the liar—not just because he writes fiction, which is inherently a lie, but also in the conduct of his life of letters: his name is also fictional, a pseudonym, and indeed he wrote under many different pen names; only The History of Painting (a collection of essays) was published under his own name.

By the way, regarding the quote above, Stendahl falsely attributed it to a real-life person. Ha ha.

Which brings me to the second work of art invoked here, Rene Magritte’s famous surrealist painting, False Mirror. Again we see the sky reflected upon an eye, but with clouds rather than trees. The title, though, is of great interest, for it suggests that what the eye literally sees is not, in fact, “the truth.” Eyes create subjective images in our minds, and given that our eyes are also selective in what they look at, they never capture an entire picture. But False Mirror is also a work of art, which begs a certain self-reflectivity of the medium: that the value of art lies not in its ability to mimetically represent the objective world around us, but to suggest through symbol and metaphor the interior reality of our consciousness. Again, our esoteric concerns seem to be justified.

Which brings me to the second work of art invoked here, Rene Magritte’s famous surrealist painting, False Mirror. Again we see the sky reflected upon an eye, but with clouds rather than trees. The title, though, is of great interest, for it suggests that what the eye literally sees is not, in fact, “the truth.” Eyes create subjective images in our minds, and given that our eyes are also selective in what they look at, they never capture an entire picture. But False Mirror is also a work of art, which begs a certain self-reflectivity of the medium: that the value of art lies not in its ability to mimetically represent the objective world around us, but to suggest through symbol and metaphor the interior reality of our consciousness. Again, our esoteric concerns seem to be justified.

With that in mind, let us consider the “discourse” of LOST, namely the kind of narrative techniques which are employed by the text, and in particular the direction. Every single shot has a focal character. Which is not to say that every shot has a person in it, but even those shots that don’t can be said to represent what a character is looking at. And so we in the audience are, by extension, limited to what the characters know and feel.

In other words, the show is, to put it in the terms of a novel, written in the third-person limited. There is no “omniscient” point of view; the eye in the sky has crashed.

LOST Through the Looking Glass (Pilot Part 1)

So, just to make a disclaimer and get it out of the way: the writers of this show are lying liars who lie. I say this not as an attack, but as praise. Lying is really the job description of fiction writers—they aren’t just liars, they are professional liars. We pay them to lie to us. We approve.

But there’s a breach here, for their lies were never restricted to the fiction itself—no, they also lied in interviews, podcasts, and other documents outside the show itself. Early in Season One, for example, after the show became a smash hit, creator Damon Lindelof was quoted as saying that the show was “firmly ensconced in science fact,” that everything in the show had a “rational explanation in the real world we all function in,” and, most hilariously, that “there is no time-travel.” Writer David Fury said, “Despite the surreal, bizarre aspects of the Island, there will be an explanation for it.”

Lies. Lies! But it’s one thing to lie about a show while it’s airing in order to preserve its mysteries through artful misdirection. It’s quite another to lie to the company that paid you to make it.

Early in the show’s production, before the show had even been green-lit, the writers came up with a “Bible” for LOST, one intended to be read by the head honchos at ABC to assuage their fears about the endeavor. This Bible promised that the show’s episodes would be self-contained, not serialized; that everything would have a scientific explanation; that a soundstage could be built to obviate constant on-location shooting in Hawaii; and that not only would the “monster” be explained within “the first few episodes,” but that there would be no overarching “ultimate mystery.”

Let us all laugh now.

So for those people who anticipated clear-cut answers to all the show’s mysteries, especially the mystery of the Island itself, at this point it’s virtually impossible to believe anything the writers or producers have to say about it, even after the fact. One writer, Javier Grillo-Marxauch, just earlier this year said, “There was definitely a sort of ‘operational theory’ for what the island would be—it was liked by some and loathed by others—and since Damon and Carlton chose not to say it out loud in the series finale, I won’t presume to do it for them.” So at least on the part of some writers, there’s a tacit admission that keeping the final secrets of the Island preserved is an ethic maintained by the authors to the present day.

Again, though, this is not a criticism on my part. For the upshot of this is that a great deal of our freedom regarding an interpretation of the show has been preserved. Appeals to authority are virtually worthless when it comes to LOST. Which is very much in line with the critical notion of the Death of the Author (again, the fall of the Eye in the Sky is terribly apt). Granted our freedom from Fate, then, let us go back and take a look at the conclusions of the Exegesis, now that it’s examined the entire corpus of LOST, and see if those ideas are supported by LOST itself.

May the Circle be Unbroken

May the Circle be Unbroken

The first thing we need to note is that the final image of LOST is a mirror-twin of its first. We began with Jack’s opening eye, and we ended with Jack’s closing eye. In both shots, he’s lying in the bamboo forest, and the dog Vincent has come to visit. So there’s a tremendous amount of continuity connecting these two shots. In making this connection, the whole of the series now forms a Circle, which was one of the working titles of the show.

Now that Jack has died, his consciousness is free to go back, to reawaken at the beginning of the series, making the Opening Eye is one of Resurrection. Time is renewed, and the Circle makes its mark.

The moment Jack his the beach, the camera slowly pans around, following his gaze, and about halfway through we hear screams coming through on the audio channel. But when the camera comes full circle, Jack is still looking the other way, and seems to be standing in a different spot, or perhaps the camera has subtly moved; regardless, the effect is disorienting, suggesting two streams of consciousness for Jack, or, perhaps, two Jacks. One who is aware at some level of what’s happening, if not exactly a conscious level, and one who’s just a bit out of sync. And now he will run through his paces again (how many times has he done this now?) as we watch along, thanks to our lovely shiny silvery DVD (well, BD-ROM) discs, a perfect demonstration of time as a flat circle.

conscious level, and one who’s just a bit out of sync. And now he will run through his paces again (how many times has he done this now?) as we watch along, thanks to our lovely shiny silvery DVD (well, BD-ROM) discs, a perfect demonstration of time as a flat circle.

The thing is, so much of the show makes sense whether it represents something happening for the first time or as part of an eternal return. For example, we can say that Jack is just tremendously competent as he efficiently and effectively takes care of the injured and wounded while weaving his way through the chaos and confusion. Or may he was efficient and effective because he’d done this all before, and so he knew where to go, and when, as best the circumstances would allow.

This works even at the show’s preferred mode, which is character-based emotional drama. When Kate first steps out of the jungle, and sees an injured Jack begging for help with his wounds, her emotional reaction can come from having just survived this traumatic event… or because she knew that Jack has died, and is sad about having lost someone she loved. And I tend to lean towards the latter, given the emotional content of the scene in question.

Likewise with some of the sound cues. At the end of the initial montage of Losties milling about after the explosions, we come to a shot of Locke sitting on the beach, alone, and the musical cue is completely ominous. Kate’s initial reaction to seeing Locke while she’s getting new shoes—almost as if she knows that the Smoke Monster will eventually take his form—is similarly prescient.

Likewise with some of the sound cues. At the end of the initial montage of Losties milling about after the explosions, we come to a shot of Locke sitting on the beach, alone, and the musical cue is completely ominous. Kate’s initial reaction to seeing Locke while she’s getting new shoes—almost as if she knows that the Smoke Monster will eventually take his form—is similarly prescient.

Verbal Copulation

Going through the show again, it’s much easier to pick up more clues and references to the central conceits of the Island. For example, the juxtaposition of Claire and Hurley—they both have big bellies—is one we’ll see again as we approach Numbers. In this, their first appearance together, we see them in identical positions on the ground. They’re also bound by repetitions and time: Claire’s having contractions, and Hurley’s timing them. And when Hurley starts handing out food, he gives a second meal to Claire.

Mostly, though, it’s the use of language that’s truly exquisite, for it’s here we see mirror-twinning become representative of the alchemical principle of equivalent exchange. Consider the exchange between Kate and Charlie during the trek. Kate starts having some déjà vu, when she thinks she recognizes Charlie. He starts singing…

CHARLIE: “You all everybody! You all everybody!” You’ve never heard that song?

KATE: I’ve heard it. I just don’t know what the hell it is—

CHARLIE: That’s us. Drive Shaft. Look, the ring—second tour of Finland. You’ve never heard of Drive Shaft?

KATE: The band?

CHARLIE: Yeah, the band.

KATE: You were in Drive Shaft.

CHARLIE: I am in Drive Shaft.

There’s an awful lot of twinning going on here—Charlie first repeats himself, then Kate repeats the word “heard,” and then they exchange “the band” and “drive shaft.” And in the midst of this exchange, Charlie invokes The Ring, which represents the second tour of Finland, holding it up for her to see. (The other Ring we see in this episode belongs to Rose, which she kisses. Jack’s CPR is what brought Rose back from the dead.)

Speaking of Drive Shaft, what an interesting metaphor. To unpack that metaphor, we must first make a slight digression and attend to another recurring motif in LOST, namely that of the Tree. The World Tree symbolizes the axis mundi that runs through the center of everything, connecting Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now. For example, Jack is reborn in the bamboo forest at the very beginning and end of the show; that it’s appropriate to connect the closing eye to the Opening Eye is confirmed by the presence of the symbol of connectivity. And of course, the principle of “as above, so below,” in which the episode’s beginning and ending images are mirror-twinned, is likewise congruent with the World Tree motif.

Interestingly, the Center marked by the axis mundi is in many myths and ritual systems the place of Eternal Return, as described Mircea Eliade in The Myth of the Eternal Return:

1. Every creation repeats the pre-eminent cosmogonic act, the Creation of the world.

2. Consequently, whatever is founded has its foundation at the center of the world (since, as we know, the Creation itself took place from a center).

So, returning to Drive Shaft, the band’s name refers to an object in mechanical engineering that most typically connects the engine of a vehicle (usually located in the front) all the way to back, before it goes to the wheels. It literally combines the schema of the axis mundi with the principle of rotation. That “Drive Shaft” in the context of the scene refers to a group of people who play music, an act of creativity if not Creation itself, well, we’ll get to that when we revisit the implications of The Looking Glass station, which connects the Island to the outside world.

Anyways, our immediate scene in question continues:

KATE: My friend Beth would freak. She loved you guys.

CHARLIE: Give me Beth’s number, I’ll call her, I’d, I’d love to.

JACK: Hey—

CHARLIE: Does she live nearby?

KATE: Have you ever heard of Drive Shaft?

CHARLIE: “You all everybody! You all everybody…”

JACK: We’ve got to keep moving.

KATE: They were good.

CHARLIE: They are good. We’re still together. In the middle of a comeback.

Again, notice the repetitions, the call and response pattern of the dialogue. Doesn’t matter if it’s about Beth, or love, or being “good,” or even the re-invocation of Drive Shaft’s greatest hit, it’s the principle of mirroring that rules here. (Incidentally, lines like “In the middle of a comeback,” invoking the Center and cyclicality, are just fucking hilarious to me now. Oh, and speaking of circularity…

KATE: Where the hell is Jack?

CHARLIE: I don’t know!

KATE: Did you see him?

CHARLIE: Yeah, he pulled me up!

KATE: Where is he?

CHARLIE: I don’t know!

KATE: How can you not know?

CHARLIE: We got separated! Look, I, I fell down, and he, he came back for me, that thing was just…

KATE: Did you see it?

CHARLIE: No. No! But it was right there. We were dead! I was. And then Jack came back, and he—he pulled me up. I don’t know where he is.

In this scene, our heroes have run from the cockpit after securing the transceiver, chased by the monster. Kate has already counted down from “five” and left the sanctuary of the Banyan trees, only to run into Charlie. Again there’s the verbal mirroring, almost as if the scene has played twice over, and has subsequently been stitched together in the editing room. Twice, Kate asks Charlie where Jack is. Twice, Charlie says he doesn’t know. Twice, Kate asks Charlie what he saw. Twice, Charlie says that Jack came back, that Jack “pulled him up.”

And then, in the end, Charlie says that they were dead. Or he was. Which is immediately followed by LOST’s most key phrase:

KATE: We have to go back for him.

CHARLIE: Go back? There? Kate, there’s a certain gargantuan quality about this thing.

Of course, we’ll be exploring exactly what it means to “go back” throughout the Exegesis. Let’s just note that it’s here, in the beginning, that the seed has already been planted.

Oceanic Airlines

Oceanic Airlines

Finally, we see a bit of this in Jack’s FlashBack, too, on the airplane:

CINDY: So, how’s the drink?

JACK: It’s good.

CINDY: That wasn’t a very strong reaction.

JACK: Well, it’s not a very strong drink.

The stewardess hands him two drinks, one of which he downs, while the other goes in his pocket. And this really stands out after the Season Six premiere, LA X, when Cindy only gave him one bottle. Of course, in LA X he doesn’t need alcohol to sanitize his wound, because in that timeline Flight 815 never crashed. But look at how tight the dialogue is—Jack is able to repeat both Cindy’s sentence construction as well as the word “drink.”

It is at this point that I want to bring up yet another recurring motif in LOST, namely that of Water. Water is special in LOST. Water is, of course, a reflective surface, “nature’s mirror.” And throughout the show, some rather significant moments occur in juxtaposition with water. Flight 815, of course, is run by Oceanic Airlines—the invocation of the Ocean conjures up our psychic depths, as well as our emotions, and so it’s absolutely perfect that the first FlashBack occurs on an Oceanic flight, and transitions to the present with a shot of the ocean itself.

Later in the episode, Jack gives water to the pilot, doing so using an Oceanic water bottle. In the earlier half of this essay, we noted that Jack was mirror-twinned with the pilot. We must now add to that mirror twinning: at the end of the series, Jacob’s ritual to confer the guardianship of the Island involves drinking water, and Jack repeats this ritual with Hurley using an Oceanic water bottle. “Now you’re like me,” he said, confirming a process of twinning between them. Here the process is once more repeated.

Later in the episode, Jack gives water to the pilot, doing so using an Oceanic water bottle. In the earlier half of this essay, we noted that Jack was mirror-twinned with the pilot. We must now add to that mirror twinning: at the end of the series, Jacob’s ritual to confer the guardianship of the Island involves drinking water, and Jack repeats this ritual with Hurley using an Oceanic water bottle. “Now you’re like me,” he said, confirming a process of twinning between them. Here the process is once more repeated.

It’s said that when the showrunners were first breaking the pilot episode, they wanted Michael Keaton to play the part of Jack, which they’d be able to afford because Michael Keaton’s character would be killed off right at the start; Kate was supposed to be the new leader of the Losties. But the network honchos refused to let them kill off the white guy. So the initial death of Jack ended up being replaced by the death of the pilot. Considering that Jack and the pilot are mirror-twinned, I’m strongly encouraged to suggest that this very technique of mirror-twinning is an alchemical response: by drawing a likeness between the two characters, one can replace the other through the process of “equivalent exchange.” We will see quite a bit of this throughout the series.

But why have such a process? Two reasons, one being diegetic (or Watsonian), the other being extradiegetic (Doylist). In the former case, it may be that if the Island is in fact a Fate Machine which requires certain events to play out, the only way to actively partake of “free will” is to substitute one piece in the “game” for a piece whose likeness won’t upset the natural course of events. In the latter case, the problem with writing a series in advance of its production is that the exigencies of production can always throw a monkey wrench into your plans: actors may drop out of the series, certain locations may not become available, network head honchos may decide you can’t kill the white guy in the first act. A form of “process control” may help to facilitate long-term plans, or at the very least ameliorate the kinds of real-life issues that always have the potential of impinging on serialized television production.

Of course, if both of these are true, then not only is the Island a sort of labyrinth of mirrors, but also an entity whose existence is breached through the Fourth Wall of storytelling, but in reverse, strangely enough. Talk about your monkey wrenches! Not to mention the implications of game theory.

CHARLIE: Might be monkeys. It’s monkeys, right?

SAWYER: Sure it’s monkeys. It’s Monkey Island.

HURLEY: Technically, you know, we don’t even know if we’re on an island.

SAYID: We’re on an Island.

This is Jane, your stewardess for the Lost Exegesis. Ladies and gentleman, the pilot has switched on the “fasten seatbelt” sign. Please return to your chairs and fasten your seatbelts. Tune in next time when we discuss the Monkey Island series of video games (given the Nintendo Project won’t, we get dibs!) as well as more interesting metaphors and pop culture references introduced in the next episode, Pilot Part 2.

September 29, 2015 @ 7:35 am

I always considered “Pilot” to be one of the rare times when the ostensible lack of an episode title is actually better than almost anything that could have been used – and Lost did episode titles better than almost anything else.

But yeah, that Jack essentially becomes the “pilot” for the group, and, indeed, for the Island, at the moment when he opens his eyes at the beginning – is a very strong piece of imagery (and, of course, it turns out that his actual mirroring is with someone who we aren’t going to meet for quite a while.)

I am fascinated by the idea that he was supposed to be killed off in the first episode though – although that’s a lot less of a stretch in terms of structure than if, say, Fox had quit after series 3 or so. I can see most the same general beats in the Island story working with other characters taking the pilot role, but… (not that playing what-if is worthwhile since even if we live in an infinite multiverse we can never know!)

Looking forward to following this series. Thanks.

September 29, 2015 @ 10:26 am

The original idea was for Jack to be killed by the Smoke Monster, leaving Kate to emerge as the Losties’ leader. And I really would have loved to see it.

September 29, 2015 @ 8:15 am

Interesting to hear they had some sort of show bible. Do we know if it had any actual details of the explanations, or just promised them?

I bought into LOST hook line and sinker, until the start of season 3 (I think) where it introduced time travel. I’m a huge fan of Dr Who, I like time travel, but it was like time travel being introduced in the middle of say… Eastenders. It just didn’t fit the mode.

Is LOST worth a rewatch? At the time the main appeal was about working out what was going on, and finding out that even the writers didn’t have a clue, well, eeesh. It’s like it was a crossword puzzle where the cryptic clues were just random phrases written down and the puzzle compiler didn’t actually know what the answers were supposed to be.

Really glad to see a new ongoing thing, by Jane no less! I’ll be following intently, despite my LOST-misgivings! 🙂

September 29, 2015 @ 8:44 am

To be clear, the “lies” described above are certainly mixed with the truth. That’s part of what makes them so effective. The “bible,” for example, has many of the character portraits as we know them already laid in. Likewise, it points out how the show can change genres from one episode to the next, which is certainly does. It doesn’t have detailed explanations or anything regarding the Island or the Smoke Monster– that was kept close to the vest.

But much therein (like the idea that the show wouldn’t be tightly serialized, but banally episodic) was specifically put there to assuage network executives to sign off on the show. And, like, I don’t know all the details about this, but I’m fairly certain that certain Mystery Boxes were always meant to stay unopened.

So it’s not that the writers didn’t have a clue. They most certainly did, and they always had a working theory of what the Island was and where they wanted to go next — at the very least, they seemed to know what effects the Island could generate, which I think is actually more interesting than any diegetic “reasoning” behind those effects… or, better yet, aesthetics.

But simply the material fact of working on a television production meant that they always had to plan on “making stuff up” as they went, and that the working model might need to change if something better came along. Which, apparently, it did.

So is LOST worth a rewatch? Absolutely. The character dramas are rich and rewarding in their own right. As to the “mystery” element, yes, use the crossword puzzle as a metaphor: one where the main words therein have always been there (until they were changed); where the clues are doled sparingly throughout the series, but without necessarily letting us know that they are clues; and where the final answer page has been torn out of the book and thrown into the sea.

Finally, regarding the introduction of time-travel in Season 3, it is my contention that time-travel has always been a part of the show, and we just didn’t know it (it hadn’t been blatantly pointed to) until Flashes Before Your Eyes. Which, you know, I’ll be getting to as we unwind all the preceding episodes.

🙂

September 29, 2015 @ 9:54 am

I was under the impression that they were winging the whole thing though. Granted, this is from half-remembered memories of interviews and stuff I’d read years back and you probably remember more. I seem to recall the pilot was written by someone different and no-one involved with the show after that point knew the resolution to things such as “what was the monster that attacked the pilot”, and that at the point season 1 ended, they didn’t actually know what would be inside the hatch. Those seem sort of key!

Or do you mean all that stuff was up in the air but not important, because the important thing was what the island was, and viewers just latched on to the more obvious and exciting mysteries?

September 29, 2015 @ 10:18 am

It was a combination of planning it and winging it.

So, take the Hatch. They wanted a Hatch from the very beginning, but didn’t know what would be inside. They played with all kinds of ideas, but Lindelof didn’t like them, and so they held back the Hatch. But once Lindelof came up with an idea he really liked (a man pressing a button every 108 minutes to save the world, which is perfect) then the Hatch was put into the show. Sure, some of the details were improvised (it’s said the idea of Hurley finding TV dinners came from the fan forums) but by and large they knew what was in the Mystery Box before they introduced it to the show.

Another example: the polar bear, which they always knew origin: part of the Dharma Initiative experiments, though before Season Two it was internally known as the Medusa Corporation. But they also improvised here, making it respond to Walt’s psychic abilities.

Lindelof, btw, was involved with the show from the very beginning and through the very end. JJ Abrams co-produced the pilot (including writing and direction); Carlton Cuse was subsequently recruited to be a co-showrunner with Lindelof, to keep the latter from going insane.

September 29, 2015 @ 10:40 am

In regards to the pilot being written by someone else, you might be mixing up the initial behind the scenes genesis of the show. The show was born when the ABC president basically wanted to have a serialized version of Survivor, and hired a writer to make a show script based on that. The initial script was rejected, and then J.J. Abrams was brought in, who later brought in Damon Lindelof (Carlton Cuse would be brought in after the pilot was picked up and Abrams left). Abrams and Lindelof’s script is the Pilot that we see, but the original writer still got a co-creator credit (and I believe basically lived off of the success of LOST despite never writing another word for it).

The lies, damned lies, and original LOST show bible presented to ABC after the Pilot was necessary because the ABC president who had originally greenlit/conceived the series was on the way out. New network presidents are usually loathe to favor the work of the old boss, so Lindelof and company had to make the show seem as appealing as possible just to remain on the air, which in this instance meant making it appear to be a procedural-like.

September 29, 2015 @ 9:18 am

Okay I gave up on Lost early on because the fact that the writers were making it up as they went along (go ahead say it…”Don’t they all?”) became less and less interesting. So, did I miss the point? I mean WAS that the point? I usually guide people who espouse the merits of Lost toward Mcgoohan’s The Prisoner which, IMO, did the same thing in 17 episodes or Twin Peaks which did it more artfully. Having said that, thanks Jane for giving me the opportunity to revisit what, at the least, must be acknowledged as a cultural marker. I’m going to enjoy watching along with your commentary and close readings.

September 29, 2015 @ 9:56 am

That reminds me of Battlestar Galactica with the ‘final five’ plot where even the writers didn’t know who the final five would be!

September 29, 2015 @ 10:24 am

The actual point of LOST is the characters. Each character is a Mystery Box, and for each character they came up with incredibly detailed backstories well before the Pilot episode. And it was always the plan that the characters would slowly be revealed over the course of the show. (The FlashBack structure, on the other hand, was a fairly late development in the genesis of the show.)

And this is really why LOST was so successful — because drama really hinges on characterization, not mythology or puzzle-boxes.

September 29, 2015 @ 10:51 am

With that I agree. But why sell a show on the premise/promise that it’s a puzzle to be solved when it isn’t? So they ‘lost’ (pun probably intended but not pre determined) me because I didn’t care about the puzzle when I might have cared about a drama based on detailed characterisation. Actually I prefer broadly painted mood pieces to detailed back stories in my drama but..whatever. I’m intrigued by your assertion that certain episodes examined different genre conventions. Anyway, you got me. I’m along for the ride and determined to enjoy it this time around (references definitely intended) 😉

Okay CAPTCHA what’ve you got for me?

September 29, 2015 @ 12:40 pm

I watched almost all of Lost, but gave up about four or five episodes before the end because I was so fed up with it.

I’m still not sure if I would have liked it more had I watched the last few episodes, but from reading a synopsis, I don’t think I missed much.

September 29, 2015 @ 3:59 pm

Are you taking guest posts for this project? Cause I’m writing this thing on the Spider-Man films in which I talk about The Ghost of a Flea, the auteur theory, and the LOST anime and it feels right for this blog.

September 29, 2015 @ 10:33 pm

LOST.

The Opening Eye. Every character driven episode, which lets me honest, is just about every episode. Opens with that eye, allowing us to delve into the aptly put, mystery box of that character.

“And so we in the audience are, by extension, limited to what the characters know and feel.”

We talked before, a little bit, about interactive television, which this show did so well. Perhaps its because we grew up on, to name a well known medium; choose your own adventure books, even down to the American Idol text to vote. We like to be involved with our entertainment.

We are on this adventure, we are LOST, we are going back. WE woke up with Jack on the floor of a jungle with the sky in our eye.

September 30, 2015 @ 9:54 am

Oh yeah, this is exciting.

September 30, 2015 @ 11:14 am

I’ve been toying with the idea of doing some sort of episode by episode analysis (walkabout?) through the series, but I can already tell from the first post that this is going to be redundant and I’ll probably enjoy reading your analysis more.

October 1, 2015 @ 6:32 pm

Yay. Lost is my second favorite TV show of all time, just behind Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and for me it held up all the way to the end. Even the worst episode of Lost is one I’d happily watch right now.

This looks to be a really good series of essays and I’m always up for delving into the wonderful world of Lost. You made some really interesting observations in here and while I don’t think most of them are intentional by the writers (not that it matters either way of course), the one that really struck me was the repetition of Jack having someone drink from the bottle in both the pilot and the finale. I cannot believe I never thought about that.

Very much looking forward to future writings from you, Jane 🙂

October 6, 2015 @ 3:52 am

Really loving reading your posts and especially excited about your perspective on Lost. Been overwhelmed a bit with work and illness, so not much comment right now but really enjoyed this – thanks!

** On a side note, just a shame I can’t seem to find anything on this site where I can follow threads, etc, as would like to keep in touch with conversations as was possible on Phil’s blog.