Love Isn’t Forever (Leather)

Leather (official bootleg, 2005)

Leather (TV performance, 2005)

Leather (official bootleg, 2007, Tori set)

Leather (live w/orchestra, 2012)

The confessional mode of songwriting is full of pitfalls for a critic, and “Leather” offers us opportunities to topple into all of them. The song creates as aggressive an intimacy as is possible: “Look I’m standing naked before you,” it opens, immediately making its singer vulnerable with regards to the listener. From there we plunge into debasement: “don’t you want more than my sex? / I can scream as loud as your last one / but I can’t claim innocence.” There is an immediate sense of knowing more than we should—a feeling that we’ve been brought into a space we do not belong.

It’s a trick, of course. To state the obvious, Amos is not standing naked before us. The line is a sly game of medium. “Look,” Amos proclaims in an entirely auditory form. “I’m standing,” she says on a recording that was already two years old when it was released to the public. “Naked before you,” she declares from a position that is almost certainly nowhere near the speaker her voice comes out of. Even in a live performance, the song is an exercise in baldly lying to the audience. To take its most semiotically dense iteration, at a 1997 benefit for the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network Amos sits on her piano bench and makes eye contact with the audience as she begins plonking the middle C note that begins the song. She bows her head, then waves briefly before sitting up and stopping to explain that the person she first sung it to is at the concert and that she hasn’t sung it to him since that time. She then lets out a single “ha,” smiles, plays the opening again, and then, clad in jeans, a black tank top, and a light red overshirt, dives into the opening line.

I recognize that I’m belaboring the point here, but without highlighting the intensity of the artifice involved in that line it’s impossible to quote something like her 2009 account of the song in Rolling Stone that “I think there was a side to me that was trying to—in the shedding—to also really collect my shadow portions. And I would go visit them and take these sides that I had judged. And one side that had been very crucified was the sexual side that did not yet understand erotic spirituality, did not know how to bring this into being. Very far away—years away from this. Little did she know when she was writing ‘Leather’ that we would be years and years away from knowing how to integrate that” without things going catastrophically wrong. And it’s even more dangerous to quote something like her 2001 interview with the UK queer magazine Boyz in which she talked about her life in LA in the years before writing “Leather” and says, “I didn’t want to be anybody’s guinea pig sexually. I was like, practise on someone else. And the whole thing with being with an older man, I guess I did have a period of that, I was with a guy who was 11 years older than me when I was 21 in LA and before that I was with a failed cat burglar. And sexually, they were both definitely not practising on me, which was good. But I’m not a sexual creature.”

Instead of thinking about “Leather” in terms of biography or intimacy, then, let’s flip the script a little. Introducing the song at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1991, Amos explains that she played it for a record executive (almost certainly Doug Morris) and his reaction was to tell her that playing the song would end her career. (“So I’m playing it,” she grins, and starts in.) Obviously this was not the case. Instead the song is one of her most iconic—one of the ten most played songs over the course of her career. Never mind what personal experience Amos was drawing on in crafting it—why is this a song that, contrary to the expectations of a record executive, literally millions of people (or, let’s go ahead and be even more specific, women) were able to relate to?

The answer is banal on several levels: a tale of soul-shatteringly bad sex is in fact instantly relatable to countless other women. For all the power to be found in triumphant reclamations of feminine sexuality, the grim reality is that female sexuality under patriarchy is largely a snooze-fest. Never mind the abuse and violence and trauma strewn across the sexual landscape for women—the overwhelming characteristic of it all is tedium. This is not to say that there are not boys who, to quote a later song, make her raspberry swirl, nor even to suggest that they are rare. It’s just that they are outnumbered by a small legion of jackhammering bores.

This is not talked about. Positive portrayals of female sexuality are barely talked about, and were even less so in 1992. It scarcely serves the patriartchy’s interests, after all, to foreground something that renders the, forgive the crudeness, receptacles of their lust as anything more than objects. And it’s even less in their interests to give voice to the fact that so many men are just plain rubbish at sex. The truth is that the public declaration of sex’s depressing inadequacy was every bit as incendiary as Morris imagined it to be—his only error was in his assessment of its marketability. And so Amos’s wry bad sex anthem, where she plaintively begs for it to just be the weather and wonders why she’s even here before ruefully accepting that she is and instructing, simply, to “hand me my leather” took fire, giving voice to countless women’s own experiences of sex’s big letdown, whether from the older and wiser perspective of someone who, like Amos(’s narrator), can’t claim innocence or from the likely more common perspective of adolescent women rapidly coming to realize that their forbidden lust ain’t all it’s cracked up to be. Or even, as Amos acknowledges, the song’s use by what she wryly refers to as “ladies that work in the other entertainment industry” where it’s been used by pole dancers, burlesque performers, and others to emphatically alienating effect. (If you can stomach the sound quality, this performance by Kat Colorful is instructive.)

And yet separating the song entirely from Amos’s own perspective is ultimately a fool’s errand. Never mind the fact that Little Earthquakes, to a degree no other album of hers comes close to sharing, demands to be read in confessional and autobiographical terms. (Though as we’ll see in time, even the song that most emphatically seals the album’s autobiographical tone is just as much built on careful artifice as this one.) Amos s simply too committed to her idiosyncrasies to put out a song that offers any sort of universal relatability. Even “Crucify,” which comes the closest to pop music’s standard promise of universalism, muddies the water with the “cat named Easter” section. And so “Leather,” in its third verse, takes a sudden swerve away from the deep relatability of bad sex and into a bewildering and inscrutable vision. The verse swings from a surreal religious image of a near-miss traffic accident with a cigar-smoking angel (the latter detail giving rise to what is by some margin the funniest vocal delivery of Amos’s career) into an ominous and cryptic prophecy: “in a sense… you’re alone here / so if you jump you best jump far.” (Note the homophonic pun of in a sense/innocence.)

The verse is the sly coverup after the teasing reveal—a sudden snapping back from the various intimacies the song has thus far offered, whether moving expressions of unspoken but widely recognized knowledge or carefully performative auditory tripteases. It swiftly reorganizes the song, establishing its identification as a one-way street. Amos understands and relates to your exhausted and dissociative experiences of bad sex; you do not quite understand or relate to hers. Even as the object of our gaze, allegedly naked before us, she’s vividly and completely in control.

Recorded in Los Angeles at Capitol Records in 1990, produced by Davitt Sigerson. Played throughout Amos’s career.

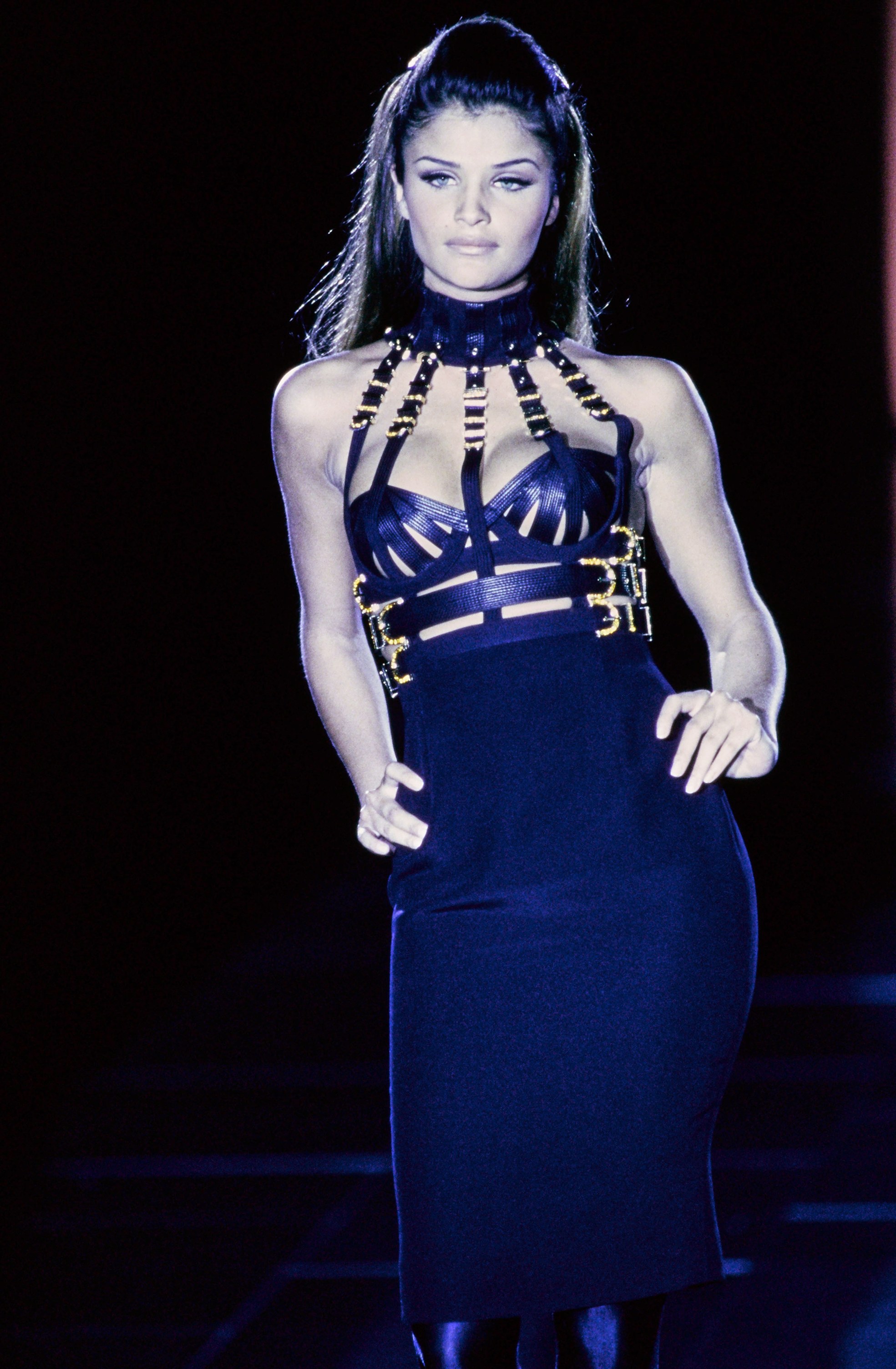

Top: Gianni Versace’s 1992 collection “Miss S&M”

Leather (live, 1991)

Leather (live, 1991)

October 29, 2019 @ 12:01 pm

No doubt, Nothing is forever 🙂

October 30, 2019 @ 9:15 am

You’re the only creator I support on Patreon and for a good reason: only you can make me read essays about songs I’ve never heard about and deeply enjoy them. Please keep being amazing.

November 13, 2019 @ 10:16 am

Subscription boxes are a type of boxes which are delivered to the regular customers in order to build goodwill of the brand. They are also a part of the product distribution strategy. As a woman, you should subscribe to these boxes to bless yourself with a new and astonishing box of happiness each month. visit mysubscriptionsboxes