The Brotherhood of Baltimore (Baltimore)

Baltimore (unreleased 1978 recording).

Baltimore (unreleased 1978 recording).

Like most pop artists, Tori Amos’s career has a vaguely embarrassing starting point. Fame comes slowly, and rarely on the first try, and most artists have some embarrassing recordings from their early efforts at success that are just waiting to be slapped up on YouTube or, in the case of “Baltimore,” tossed into VH1’s Before They Were Stars, a series dedicated to exactly this. The five minute segment in which this was publicly unearthed sticks mostly to a simplistic biography in which Amos’s piano bench gyrations in the “Crucify” video are juxtaposed with her upbringing as the daughter of a minister. The complexity of the story is acknowledged, but the underlying point is unequivocally rooted in teasing Amos for the naive innocence of her upbringing. “Baltimore” is introduced in a veering segue as the segment goes from the infamous image of Amos breastfeeding a pig in the Boys for Pele liner notes to her parents talking with rueful amusement about her love of shocking them, at which point the voiceover interrupts them to say “if you think that’s shocking…” as a leadup to Amos performing “Baltimore” on local television.

It’s cynical, more than slightly sexist, and ultimately effective, mostly because “Baltimore” is, at first glance, an absolutely ridiculous song, doubly so coming from Tori Amos. Its opening peel of morning show piano backed with a daydrinking hi-hat is utterly laughable in its twee insistence, and that’s before you get to the lyrics about how “the sun sets across the bay / I‘m glad to spend my day / in a working American city / with the people who made it that way.” Everyone knows exactly what this track is: a work of juvenile over-sincerity—a cloying love letter from a not-yet-world weary Tori Amos to her beloved hometown for a 1980 contest to pen a song for the Baltimore Orioles.

Virtually every part of this, however, is wrong. Let’s start with the notion that “in Baltimore / love is what you find,” as it is substantially more bathetic than many alternatives. Had Tori Amos written a jingle for her local baseball team in New York or Los Angeles, the sense of naive enthusiasm would still have been tangible, but the result would not have been ridiculous per se. Had she penned an ode to the Kansas City Royals or the Cincinatti Reds, it would have been slightly absurd, but in the sense of a disproportion between the song’s enthusiasm and the apparent cultural significance of the city. But with Baltimore she has a subject whose reputation is the polar opposite of the saccharine camaraderie she’s singing about.

The end effect is much like “Good Morning Baltimore,” the opening number of the 2002 musical adaptation of John Waters’s 1988 film Hairspray. In it, the main character, overweight but cheerful high school student Tracy Turnblad, wakes up and sings the praises of her city. But unlike “Baltimore,” “Good Morning Baltimore” is unequivocally playing with the irony of being so cheerful about Baltimore in particular, having Tracy sing about how “the rats on the street / all dance round my feet” and greeting “the flasher who lives next door” and “the bum on his barroom stool” as she goes to school, eventually missing the bus and hitching a ride on a garbage truck.

The original 1988 Hairspray, however, was already an outlier in John Waters’s career, which is more accurately represented by the detail that Waters cameoed as the flasher in the 2007 movie version of the musical. Hairspray was a PG-rated attempt at popular success from a director better known for films like 1972’s Pink Flamingos, which features the legendary drag queen Divine playing a fictionalized version of herself as she goes to extraordinary lengths to retain the title of “filthiest person alive.” The film features a sex scene in which a live chicken is crushed between the two participants, a rectal lip sync performance to the Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird,” and, in the film’s final and most infamous sequence, Divine eating dog feces.

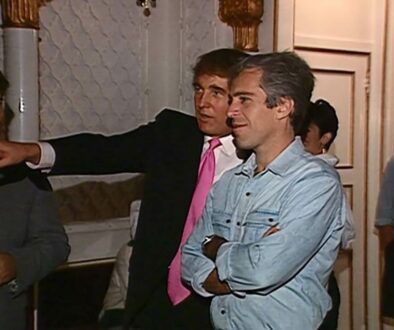

Pink Flamingos is set in Phoenix, Maryland, a suburb of Baltimore that’s just slightly further to the north than Lutherville, where Waters grew up. Baltimore at large was a consistent muse and subject for Waters’s films, which collectively chronicle a vision of the city that is long on both camp and giddy, subversive shock of the sort that Pink Flamingoes trades on. But this vision of extravagant vulgarity is scarcely the whole of Baltimore’s cultural standing, nor of the song’s ironic register. The more typical image of Baltimore is something more along the lines of Donald Trump’s description of Representative Elijah Cummings’s congressional district, which encompasses most of the city, as “a disgusting, rat and rodent infested mess” that is a “very dangerous and filthy place.” This account, of course, is informed primarily by Trump’s virulent racism and personal animosity for Cummings, who had recently had the temerity to point out that concentration camps are bad, but Trump is playing with an existing cultural perception of the city as, broadly speaking, a rough one.

A more nuanced and informed perspective on the city can be found in David Simon’s magnum opus The Wire, which over the course of five seasons chronicled in meticulous detail the precise contours of an endemically crime-ridden city. Starting from a minute analysis of the cat and mouse games between cops and one of Baltimore’s many drug gangs and working its way up through the demise of blue collar shipping jobs, the futility of reformist politics, the hopelessness of the educational system, and the impotence of the news media, Simon and his team paint a picture of a city with vast, interconnected, and largely unfixable problems—a vision of his hometown that is at once intensely loving and firmly pessimistic on anything save for the individual level.

A more nuanced and informed perspective on the city can be found in David Simon’s magnum opus The Wire, which over the course of five seasons chronicled in meticulous detail the precise contours of an endemically crime-ridden city. Starting from a minute analysis of the cat and mouse games between cops and one of Baltimore’s many drug gangs and working its way up through the demise of blue collar shipping jobs, the futility of reformist politics, the hopelessness of the educational system, and the impotence of the news media, Simon and his team paint a picture of a city with vast, interconnected, and largely unfixable problems—a vision of his hometown that is at once intensely loving and firmly pessimistic on anything save for the individual level.

The path by which Baltimore became the city of Waters and Simon’s visions, however, was a long one. It starts approximately thirty-five and a half million years ago, towards the end of the Eocene, when a meteor struck near the tip of what is currently the Delmarva Peninsula in Virginia, setting off a tsunami that reached the Blue Ridge Mountains, and creating a fifty-three mile wide underwater impact crater. Thirty-five million years and change later, the end of the ice age flooded the area, forming the Chesapeake Bay, as well as cutting a number of rivers into the land, including the Patapsco.

This led, in approximately 10,000 BC, to human settlement by Paleo-Indians at the point where the Patapsco emptied into the bay, and the area was occupied continually for the subsequent millennia. In 1608, the river was scouted by John Smith (aka that guy voiced by Mel Gibson in the Disney film) in the course of a larger expedition to find food for the then-starving Jamestown colony. Proper European settlement of the area began in 1634 after Cecilus Calvert, was granted the charter previously intended for his late father, the first Baron Baltimore, named for Baltimore Manor in County Longford, Ireland. In 1659, the colony was divided into twenty-three counties, one of which was named after Lord Baltimore. Two years later, David Jones commenced construction on the earliest part of the city proper, with other settlers filing in over the next couple of decades.

Finally, in 1729, the Maryland General Assembly established the Town of Baltimore. Over the remainder of the century, the city gradually expanded by draining and filling marshes, becoming the largest city in the mid-Atlantic colonies. During the American Revolution, it served for three months as the seat of the Second Continental Congress, and saw a boom in shipbuilding spurred by the authorization of privateers, but was spared any actual fighting. The next war, however, was more substantial—following the burning of Washington in August of 1812, British forces set their sights on Baltimore, attacking it in September at the Battle of North Point. During the successful defense of the city a lawyer, Francis Scott Key, found himself on a British ship trying to negotiate the release of an American prisoner when the ship began the bombardment of Fort McHenry, from which the defense of the city was being waged. Looking at the American flag still waving the next morning, he penned four stanzas under the title “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” but these days better known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Finally, in 1729, the Maryland General Assembly established the Town of Baltimore. Over the remainder of the century, the city gradually expanded by draining and filling marshes, becoming the largest city in the mid-Atlantic colonies. During the American Revolution, it served for three months as the seat of the Second Continental Congress, and saw a boom in shipbuilding spurred by the authorization of privateers, but was spared any actual fighting. The next war, however, was more substantial—following the burning of Washington in August of 1812, British forces set their sights on Baltimore, attacking it in September at the Battle of North Point. During the successful defense of the city a lawyer, Francis Scott Key, found himself on a British ship trying to negotiate the release of an American prisoner when the ship began the bombardment of Fort McHenry, from which the defense of the city was being waged. Looking at the American flag still waving the next morning, he penned four stanzas under the title “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” but these days better known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

By the early nineteenth century Baltimore was known as the Monumental City after an 1827 visit of President John Quincy Adams in which he used the term as a double entendre referring to both the city’s distinctive skyline and architecture (to this day it has more statues and monuments per capita than any other city in America) and its survival in the war fifteen years prior. The same year, work began raising capital for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and two years later the first train built in America, the Tom Thumb, went rolling down the line.

As the largest city of a state right on the border of what would become the Confederacy, Baltimore saw unsurprising tensions in the ramping up towards the Civil War. The city had become a destination for former slaves who had worked farms in the region, while a variety of pressures led to a high rate of manumission within the city, and by the time the war broke out it had the largest community of free blacks in the countries. Nevertheless, tensions persisted, and a few months after Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration in 1861 a riot broke out when northern militia units en route to Washington were beset by a pro-Confederate mob and fired back, resulting in the deaths of four soldiers and twelve civilians. Among those dead was Francis X. Ward, whose friend, the poet James Ryder Randall, penned “Maryland, My Maryland” in response. The poem, which opens with the line “The despot’s heel is at thy shore,” referring to Lincoln, exhorts the state to “avenge the patriotic gore / that flecked the streets of Baltimore” by joining the Confederacy in the war, and, set to the same melody as “O Tannenbaum,” became the Maryland state anthem in 1939.

Following the war, the already substantial black population of Baltimore exploded as ex-slaves migrated to the city in droves, resulting in the largest black population of any northern city, creating substantial racial tensions even as the city enjoyed an industry-fueled economic boom that led to the city’s population doubling over the course of thirty years, which by the start of the twentieth century had hit half a million.

Come 1904 the city burned, with seventy blocks and over 1500 buildings destroyed, resulting in extensive urban renewal efforts that kept the city as a major industrial center through the Second World War. This, however, marked the city’s peak, with a population of just under a million in 1950. American manufactiring subsequently entered a slow decline. Over the next twenty years a gradual exodus of white residents towards the suburbs combined with a continued northward migration of blacks leaving the Jim Crow south resulted in an explosion of the black population; while the overall population held roughly steady, declining only by about 5%, the black population surged from about 24% to 46%.

This came with problems, the bulk of them imposed on the city by redlining, aggressive criminal justice policies that disproportionately targeted African Americans, and the economic stresses of deindustrialization. In 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Baltimore was one of the cities to see riots, which Spiro Agnew, the then-governor of Maryland responded to by sending in the National Guard, and, subsequently, requesting federal troops from Lyndon Johnson. Ultimately, eleven thousand troops combined with two thousand cops proved sufficient both to quell the unrest and to propel Agnew to the top of Richard Nixon’s list of potential Vice Presidential candidates on the grounds that he’d appeal to racist white people seeking a “law and order” candidate.

This came with problems, the bulk of them imposed on the city by redlining, aggressive criminal justice policies that disproportionately targeted African Americans, and the economic stresses of deindustrialization. In 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Baltimore was one of the cities to see riots, which Spiro Agnew, the then-governor of Maryland responded to by sending in the National Guard, and, subsequently, requesting federal troops from Lyndon Johnson. Ultimately, eleven thousand troops combined with two thousand cops proved sufficient both to quell the unrest and to propel Agnew to the top of Richard Nixon’s list of potential Vice Presidential candidates on the grounds that he’d appeal to racist white people seeking a “law and order” candidate.

It is here, however, that we come to the second thing that is wrong with the general understanding of “Baltimore.” When Amos sings that she’s “got a homestead on Baltimore street,” what she in fact means is that she lives with her parents in Rockville, Maryland, a DC suburb just outside the Beltway. She’d lived briefly in Baltimore as a child, moving there in 1966 when she was about two-and-a-half when her father was hired as the minister at a Methodist church in the city, and leaving in 1972 just before her ninth birthday, part of the fully 14% of the city’s population to leave over the course of the decade, most of them white.

By this time she’d been playing the piano for years, having first started playing of her own accord and by ear at the age of two and a half—early enough that she has no pre-piano memories. Amos quickly established herself as a child prodigy, and became the youngest person to be admitted to the Peabody Conservatory at the age of five-and-a-half. This proved a frustrating experience, as Amos was already adept at playing by ear, and found being sent back to easy material so that she could learn proper technique and sight-reading skills a frustrating and degrading experience. (As she wryly tells it, “They started me with Hot Cross Buns. When you go from Gershwin to Hot Cross Buns it’s a bit of a shock.”)

At around the same time she got into the Peabody, Amos first started being exposed to contemporary rock music, both through her brother Mike, ten years her senior, who would play her popular records, and from her classmates at the Peabody, most of them also a decade older than her. She gravitated towards the Beatles (particularly Sergeant Pepper), Hendrix, the Doors, and Led Zeppelin, coming to the simplistic but common view that if Mozart was a alive in the mid-twentieth century these were the artists he’d be into. Over the course of the next five years she grew increasingly interested in pop music, and when it came time to audition for her sixth year scholarship she deliberately sabotaged it by, in various accountings, either playing classical music with too many rock influences or playing Beatles music outright.

However much she may have been the architect of her own downfall, this outcome was devastating to her, and she felt torn between her own desires and her father’s evident desire for her to succeed at the Peabody. But it was in not a setback that ever endangered her focus on music. She continued private lessons, and two years later, at the age of thirteen, began playing bars in Georgetown, with her father chaperoning her, including to one of the local gay bars. Her skill at playing by ear meant that she quickly amassed a massive repertoire of songs, topping out at around 1500, but she also began focusing on her own compositions. And it is out of this period of her life that “Baltimore” emerged.

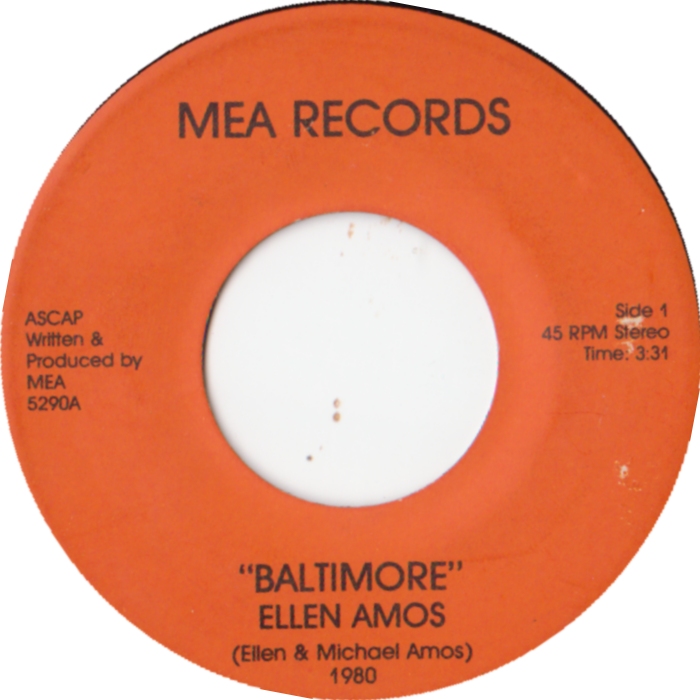

The most commonly heard version of “Baltimore”—the one used in the VH1 show, for instance—is from a 1980 self-pressed single. There the song is credited as a co-composition of Tori and her older brother Mike, who, in the popular accounting, penned the song as part of a competition run by the Orioles, and is typically treated as her first recording. This too, however, is wrong, as devoted Toriphiles will tell you, pointing to the even more obscure 1978 cut “It’s a Happy Day,” a song written by a local woman who hired Amos and a backing band to cut a demo she could shop around. That song will be dealt with in a Patreon-exclusive post along with some other early demos that have surfaced, but it turns out that it’s not the earliest extant professional Tori Amos recording either: Baltimore is.

The most commonly heard version of “Baltimore”—the one used in the VH1 show, for instance—is from a 1980 self-pressed single. There the song is credited as a co-composition of Tori and her older brother Mike, who, in the popular accounting, penned the song as part of a competition run by the Orioles, and is typically treated as her first recording. This too, however, is wrong, as devoted Toriphiles will tell you, pointing to the even more obscure 1978 cut “It’s a Happy Day,” a song written by a local woman who hired Amos and a backing band to cut a demo she could shop around. That song will be dealt with in a Patreon-exclusive post along with some other early demos that have surfaced, but it turns out that it’s not the earliest extant professional Tori Amos recording either: Baltimore is.

This version was, like “It’s a Happy Day,” recorded in 1978 at the Hallmark studios in Owings Mill, Maryland. It was uploaded to Soundcloud with little fanfare by producer Remy Ann David five years ago. A couple of clues point to it pre-dating “It’s a Happy Day”—the most thorough account of that recording, an unpublished letter to the editors of Record Collector Magazine by Richard Handal, who spoke with Camilla Wharton, the writer of “It’s a Happy Day.” Handal’s account has Amos at “mere days past her fifteenth birthday” and says that she was recommended by the studio, who was already familiar with her. David’s account of “Baltimore,” meanwhile, firmly puts her at fourteen and still living in Silver Spring (her family moved to Rockville in June of 1978), and asserts that it was the first time she’d ever worked with a backing band, whereas Handal’s account has her sufficiently familiar with the process to take charge of the recording and arrange the song on the spot for the band provided. (David’s account also describes an even earlier recording session of her own material that was how she became acquainted with Amos. These would be a fascinating find, but are deeply unlikely ever to surface: David recounts that the recordings were lost in a studio fire, and while it’s possible and even probable that the Amos family has copies, they’ve understandably shown no interest in releasing her juvenilia.)

The 1978 version is much the same song as the more familiar version, but there are some significant changes. For one, it’s considerably more downtempo, clocking in at around 68 bpm, versus 1980’s 78. This, along with an added flute solo, adds about a minute to its length. There are also several lyrical changes. For one, Amos’s non-existent homestead has been moved to Hanover Street. More significantly, there are no references to the Baltimore Orioles—the “I’ve got Oriole baseball on my mind” lyric is changed to the “to enjoy the brotherhood of Baltimore” that appears on the second chorus, while the end of the second verse (“Jump in a taxi / for 33rd street / knowing I’ll be watching those Birds go / watching Weaver’s show,” Earl Weaver having been the manager at the time) is simply a repetition of the “its all kinds of people/ familiar places, smiling faces” line from the first verse.

The absence of any Orioles references in the original version rubbishes any idea that the song was composed for a contest involving the team, but the truth is actually not that far off. As David explains, she became aware of a contest for local bands to write a song about Baltimore and so decided to put a group together to enter. She tapped Amos to write the song and sing lead vocals, while another local band of teenagers that she describes as being in the vein of Earth, Wind, and Fire provided music. “Unfortunately,” as David puts it, “some other lousy rock band won the contest. They were all guys in their later 20s and 30s. Their song sucked big bananas.”

By 1980, Amos was cutting demos of a lot of her stuff. The bulk of these to have surfaced will be dealt with in the aforementioned Patreon post, but she also booked another studio session to cut a new version of “Baltimore,” now with the Orioles lyrics, and another song, “Walking With You,” which served as its b-side. (Patreon for that one too; best not to kill our momentum here with a ton of juvenilia.) For this, she tapped a friend’s brother, Max Welker, to produce at Track Studios, along with a couple of other session musicians, most of who’s names are lost. This appears to have been part of a concentrated effort at generating some local publicity; the redone song got Amos a commendation from then-Baltimore mayor William D. Schaefer, and Amos got a write-up in the Washington Post a few months later in which Amos claimed to have written the song to cheer the Orioles on to the American League’s eastern division title. (They were beaten out by the Yankees.)

By 1980, Amos was cutting demos of a lot of her stuff. The bulk of these to have surfaced will be dealt with in the aforementioned Patreon post, but she also booked another studio session to cut a new version of “Baltimore,” now with the Orioles lyrics, and another song, “Walking With You,” which served as its b-side. (Patreon for that one too; best not to kill our momentum here with a ton of juvenilia.) For this, she tapped a friend’s brother, Max Welker, to produce at Track Studios, along with a couple of other session musicians, most of who’s names are lost. This appears to have been part of a concentrated effort at generating some local publicity; the redone song got Amos a commendation from then-Baltimore mayor William D. Schaefer, and Amos got a write-up in the Washington Post a few months later in which Amos claimed to have written the song to cheer the Orioles on to the American League’s eastern division title. (They were beaten out by the Yankees.)

All of which points towards the final thing that is wrong about the popular understanding of “Baltimore,” which is that the song is the product of naive earnestness. It’s true that Amos’s early compositions are generally slightly doe-eyed love songs, but nothing else from the period is as unrepentantly bubblegum as “Baltimore.” This is someone who was well-steeped in counterculture, used to playing for tips at nightclubs and gay bars, and generally far more savvy about what the world was like than any earnest reading of “Baltimore” would support. The giveaway is her lyrical changes for the 1980 version, layering in a publicity-friendly local hook to coincide with the Orioles’ shot at the post-season. One could call it cynical, but the more honest and accurate descriptor would be professional.

For all its future comedic potential, “Baltimore” is best understood as a work of cool, competent professionalism. Amos was given a brief—write a song for a contest about Baltimore—and she did the job, turning in a piece of effective schmaltz that, even if it didn’t win the contest, was enough to get her the exact local interest news coverage it was designed for two years later. It was competent work from someone who was quickly mastering how to make money in the grotty trenches of the music industry. A decade later, these skills would serve her at once well and disastrously when she made her first attempt at pop stardom. But even as a teenager, they were as well-honed as her piano skills themselves—a clear sign, if not of an artistic visionary, of someone who was going to make it as a professional musician.

Recorded in 1978 at Hallmark Films & Recordings Studio. Produced and mixed by Remy Ann David and Phil Brecher, with unknown backing musicians. Re-recorded in 1980 at Track Studios in Silver Spring. That version was produced by Max Welker, who also played guitar, and had Tim Murphy on saxophone along with unknown other musicians, and released as a single. Amos played a fragment of it in a 1996 concert in Amsterdam in laughing response to an audience request, but no recording of this exists.

Top: Divine mural in Baltimore; the Barksdale gang; the Battle of Fort McHenry; the National Guard on the streets of Baltimore during the 1968 riots; “Baltimore” single; a young Myra Ellen Amos

August 5, 2019 @ 4:53 pm

Most team-specific baseball songs are terrible. There are few rare gems, like “Tessie” or “All the Way,” but then you have terrible, cheesy dreck like “Orioles Magic.” “Baltimore,” in its Orioles version, is a better, more interesting song, yet “Baltimore” is basically forgotten among the Orioles faithful while “Orioles Magic” remains as beloved as Natty Boh. (In a strange but true fact, my grandfather’s cousin Don Fenhagen designed Mr. Boh, the beloved one-eyed mascot of Natty Boh, in the 1950s.)

August 6, 2019 @ 12:44 am

I don’t have much familiarity with Amos’ music, but this was a fascinating start, and I’m absolutely along for the ride. (And will join the Patreon soon).

August 8, 2019 @ 7:49 pm

Wow I did NOT expect a blog about Tori Amos to start by touching on paleogeology, Pink Flamingos, or Spiro Agnew

…but that’s exactly what I love about Dr. Sandifer’s writing. And that’s why I’m on board for this next blogging project (and will keep funding the patreon) even though I don’t know whether I’ve ever listened to a Tori Amos song

August 9, 2019 @ 12:35 pm

Great to be along for the ride with this! Excellent stuff – and hah! So good, you brought us all the way to and from the Eocene.

Again, brilliant and thanks El!