Lost Exegesis (Tabula Rasa)

One of the problems with Pilot episodes is that they’re made specifically in order to hook people (almost like fish) not just into watching a TV show, but to actually sign off on it being produced. As such, they tend not to be as representative of the series as a whole. So what a TV show has to do after its pilot is to kind of hit the reset button and start playing its cards, showing us what we might expect on a weekly basis going forward. As such, Tabula Rasa is a rather aptly named episode, given that it’s a fresh start for LOST, employing a number of techniques that we did not see previously.

One of the problems with Pilot episodes is that they’re made specifically in order to hook people (almost like fish) not just into watching a TV show, but to actually sign off on it being produced. As such, they tend not to be as representative of the series as a whole. So what a TV show has to do after its pilot is to kind of hit the reset button and start playing its cards, showing us what we might expect on a weekly basis going forward. As such, Tabula Rasa is a rather aptly named episode, given that it’s a fresh start for LOST, employing a number of techniques that we did not see previously.

For starters, we get a “Previously, on LOST” segment. It’s the sort of thing we’re all familiar with, nothing new under the sun in terms of TV, but just its very presence indicates what kind of show we’re dealing with, namely something that’s serialized. The vignettes in this segment briefly depict: the plane crash; the man wounded by shrapnel in his gut and Kate’s apparent interest in him; the fact no one has come yet to the Losties’ rescue; and a recapitulation of Locke’s explanation of backgammon to Walt (“Two players, two sides, one is light, one is dark”), that ends with Locke’s question to Walt, “Do you want to know a secret?”

The thing about a “previously” is that it’s supposed to remind us of what’s actually relevant in the previous episodes in terms of understanding what occurs in this one. Notably, then, we do not get anything about the Monster that tears down trees, or the Frenchwoman’s transmission, even though a significant portion of the character interactions in Tabula Rasa have to do with these big mythology questions. Furthermore, that bit with Walt and Locke is relatively long given that both characters are only part of a rather minor secondary plot thread in this episode. On the other hand, it certainly plays into the final shot of the episode, a shot full of foreboding, so it’s not like it’s pointless or anything.

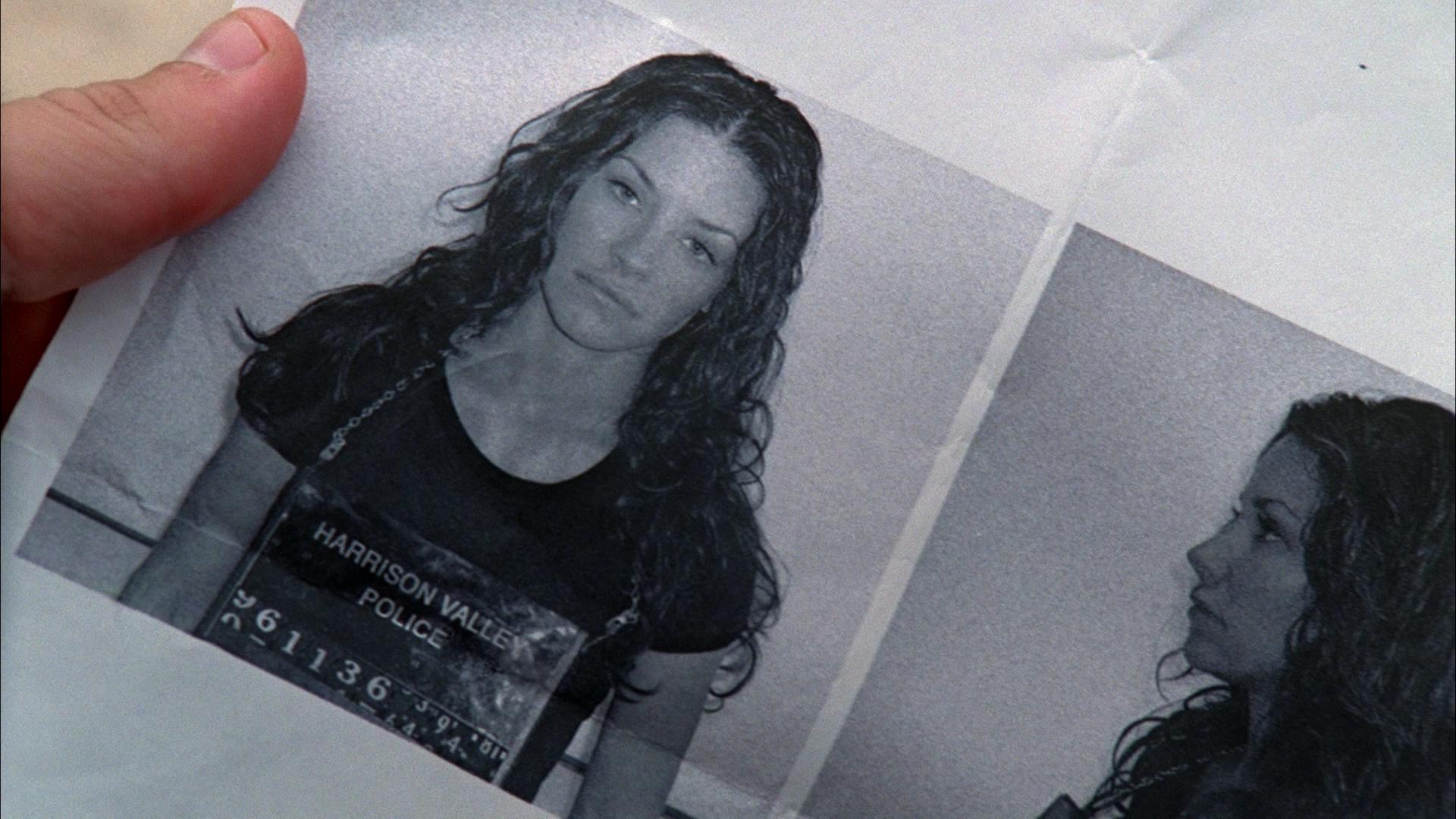

Another new element is the use of a “cold open” before the show’s title card. It’s actually here that the two major mysteries established in the pilot episodes are recapitulated, as well as establishing the focus of the episode, namely the discovery of Kate’s mug shot by Jack and Hurley.

So it should not be too surprising that the episode ends up being Kate-centric. And that’s a term I use very specifically, given the third major conceit introduced by Tabula Rasa – the episode features five Flashbacks, all of them about Kate. The Flashbacks themselves end up serving as the B-plot of the episode, detailing Kate’s time in Australia: a drifter, she ends up getting work at Ray Mullen’s farm, but he betrays her for a $23,000 rewards, setting up her capture by the Marshal. So not only do we see how she ended up on the plane, we also get a hefty amount of characterization – Kate would do almost anything to escape, like crashing Ray’s truck, but when the truck catches fire she pulls him to safety, at the cost of her own freedom.…

.png) By Anna Wiggins

By Anna Wiggins \

\ It is, in many ways, the most Part One of the two-parters we’ve had so far. Which is as it should be. I mean, it comes right out, first thing, and proclaims “we’re doing Zygon ISIS.” Pretty much right there, you’ve justified your second part. This isn’t some premise that requires a stealthy inversion at the halfway mark to work over ninety minutes. This is just an incredibly meaty, dense concept that it would be a travesty to even attempt in forty-five. Which makes it a beast to review, of course, but oh well.

It is, in many ways, the most Part One of the two-parters we’ve had so far. Which is as it should be. I mean, it comes right out, first thing, and proclaims “we’re doing Zygon ISIS.” Pretty much right there, you’ve justified your second part. This isn’t some premise that requires a stealthy inversion at the halfway mark to work over ninety minutes. This is just an incredibly meaty, dense concept that it would be a travesty to even attempt in forty-five. Which makes it a beast to review, of course, but oh well. What’s perhaps odd is that Moore did not, at least at first, really differ from that belief. Indeed, the way in which Moore describes his falling out with the company is telling: “I was starting to realize that DC weren’t necessarily my friends.” Because it’s crucial to realize, Moore really did think they were. That’s the entire reason he never actually read the Watchmen contract: he trusted the people handing it to him had his best interests at heart. This was, of course, many things; hopelessly naive, for one. An almost inevitable extension of his honor among thieves approach to creating art, for another. But, perhaps most crucially, it was more or less how people like Paul Levitz were encouraging him to think. And so when Levitz subsequently got into a dispute with Moore and Gibbons shortly after Watchmen launched over whether or not they deserved royalties on the replica bloodstained yellow smiley badges that were being widely sold in comic shops (a dispute that was over, at most, a couple thousand dollars) and made a grand show of agreeing to a royalty without conceding the legal point by which DC had originally argued the badges, despite being sold in comic shops, were “promotional items,” Moore was understandably rattled, minor as the issue was. And when, later in 1986, Jeanette Kahn had lunch with Moore and Gibbons and made an off-handed comment about doing some Watchmen prequels and how “of course we wouldn’t do this if you were still working for us,” Moore was once again rattled by what he took as a threat. Indeed, as Moore put it when describing the incident in an interview four years later, “I really, really, really don’t respond well to being threatened. I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me on the street; I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me in any other situation in my life. I can’t tolerate anyone threatening em about my art and my career and stuff that’s as important to me as that. That was the emotional breaking point. At that point there was no longer any possibility of me working for DC in any way, shape, or form.”

What’s perhaps odd is that Moore did not, at least at first, really differ from that belief. Indeed, the way in which Moore describes his falling out with the company is telling: “I was starting to realize that DC weren’t necessarily my friends.” Because it’s crucial to realize, Moore really did think they were. That’s the entire reason he never actually read the Watchmen contract: he trusted the people handing it to him had his best interests at heart. This was, of course, many things; hopelessly naive, for one. An almost inevitable extension of his honor among thieves approach to creating art, for another. But, perhaps most crucially, it was more or less how people like Paul Levitz were encouraging him to think. And so when Levitz subsequently got into a dispute with Moore and Gibbons shortly after Watchmen launched over whether or not they deserved royalties on the replica bloodstained yellow smiley badges that were being widely sold in comic shops (a dispute that was over, at most, a couple thousand dollars) and made a grand show of agreeing to a royalty without conceding the legal point by which DC had originally argued the badges, despite being sold in comic shops, were “promotional items,” Moore was understandably rattled, minor as the issue was. And when, later in 1986, Jeanette Kahn had lunch with Moore and Gibbons and made an off-handed comment about doing some Watchmen prequels and how “of course we wouldn’t do this if you were still working for us,” Moore was once again rattled by what he took as a threat. Indeed, as Moore put it when describing the incident in an interview four years later, “I really, really, really don’t respond well to being threatened. I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me on the street; I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me in any other situation in my life. I can’t tolerate anyone threatening em about my art and my career and stuff that’s as important to me as that. That was the emotional breaking point. At that point there was no longer any possibility of me working for DC in any way, shape, or form.”

This week I’m joined by Caitlin Smith, aka

This week I’m joined by Caitlin Smith, aka  William Shakespeare lived at the end of the reign of Elizabeth I and the start of the reign of James I (and VI of Scotland). This was a time when modernity was coming into being. Feudalism was crumbling and fading, and the capitalist epoch was in the process of being born. That’s why we call his time the Early Modern Period (another name for the Renaissance, basically). Modernity is essentially another way of saying capitalism, from its beginnings as a predominant social system onward. (We won’t here argue about whether we currently live in post-modernity.)

William Shakespeare lived at the end of the reign of Elizabeth I and the start of the reign of James I (and VI of Scotland). This was a time when modernity was coming into being. Feudalism was crumbling and fading, and the capitalist epoch was in the process of being born. That’s why we call his time the Early Modern Period (another name for the Renaissance, basically). Modernity is essentially another way of saying capitalism, from its beginnings as a predominant social system onward. (We won’t here argue about whether we currently live in post-modernity.) Batgirl #45

Batgirl #45