I Don’t Speak German, Episode 13 – Gavin McInnes and The Proud Boys (with guest Samantha Kutner)

Special episode this week. Daniel has a special guest, Samantha Kutner, self-described ‘Proud Boy whisperer’ to talk about Gavin McInnes and the Proud Boys. (Jack gets out of the way to let the grown-ups talk.)

Warnings apply, as always.

Direct Download / Permalink / IDSG at iTunes

*

Show Notes:

Things Gavin McInnes has Written for Taki Mag

https://www.takimag.com/article/the_west_is_history_gavin_mcinnes/

Gavin McInnes citing the ’14 words’ (with “western” replacing “white”)

Proud Boys as a Radicalization Vector (His Threats are echoed in articles below)

https://officialproudboys.com/proud-boys/fighting-media-academics/

https://notvice.com/gavin-white-supremacy-article-agreement-page-160a4b5c9037

Islamberg Conspiracy Theory

https://twitter.com/jjmacnab/status/1105884338174881792

Proud Boys Articles

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proud_Boys

https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/inside-miami-alt-right-and-proud-boys-chapter-10945821

https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-the-proud-boys-became-roger-stones-personal-army-6

*

What You Can Do

Get Involved With Light Upon Light & CTRL-ALT-DEL-HATE Campaign

https://www.gofundme.com/light-upon-light

Support the Development of the Proud Boys Incident Map and Dashboard https://www.patreon.com/ashkenaz89

Proud Boys Incident Map

https://twitter.com/ashkenaz89/status/1051237360338259969

Defector Narrative Project

https://www.patreon.com/posts/proud-of-your-on-25219991

Fash Fatigue Resources

https://medium.com/@ashkenaz89/introducing-the-fash-fatigue-chronicles-34b80c679698

*

SK Medium article on Roger Stone / Proud Boys

*

Twitter handles of people doing the work

…

CW: Discussions of Jimmy Savile and sexual assault.

CW: Discussions of Jimmy Savile and sexual assault. charts and appearing on what seemed like every TV program in the UK, Bush did an extensive amount of traveling, visiting West Germany, the Republic of Ireland, the Netherlands, France, the United States, Canada, and Japan. One could unpack any one of these tips individually, but they mostly consist of Bush performing songs from The Kick Inside. As Dreams of Orgonon is a song-by-song blog, we analyze episodes in Kate Bush’s career through the lenses of new songs as they come. Bush’s promotional visit to Japan in June of 1978 not only offers a couple songs we haven’t heard her sing before, even if they are covers, but it gives a chance to see what Kate Bush does when she’s not doing Kate Bush things.

charts and appearing on what seemed like every TV program in the UK, Bush did an extensive amount of traveling, visiting West Germany, the Republic of Ireland, the Netherlands, France, the United States, Canada, and Japan. One could unpack any one of these tips individually, but they mostly consist of Bush performing songs from The Kick Inside. As Dreams of Orgonon is a song-by-song blog, we analyze episodes in Kate Bush’s career through the lenses of new songs as they come. Bush’s promotional visit to Japan in June of 1978 not only offers a couple songs we haven’t heard her sing before, even if they are covers, but it gives a chance to see what Kate Bush does when she’s not doing Kate Bush things. It’s January 1st, 2017. Did you guess that Rockabye were at number one with “Clean Bandit”? If so, well done. Zara Larsson, Little Mix, Bruno Mars, and Wham also chart, the latter with a post-Christmas surge for “Last Christmas.” In news, US troops withdraw from Afghanistan, Obama imposes sanctions against Russian intelligence agencies for interfering with the election, and Nevada’s marijuana legalization goes into effect.

It’s January 1st, 2017. Did you guess that Rockabye were at number one with “Clean Bandit”? If so, well done. Zara Larsson, Little Mix, Bruno Mars, and Wham also chart, the latter with a post-Christmas surge for “Last Christmas.” In news, US troops withdraw from Afghanistan, Obama imposes sanctions against Russian intelligence agencies for interfering with the election, and Nevada’s marijuana legalization goes into effect. As it’s come up a few times and I’ve thus far only said it on Twitter, I figured I should make a quick statement on the site. Short form: I have decided going forward that I will no longer be covering Big Finish material on the site or in my books. There are a handful of existing obligations I’ll still fulfill. I’ve promised Andrew Hickey I’ll cover Doctor Who and the Pirates in the revised Volume 6, and while I’m going to swap out one or two of the mooted 7th Doctor Big Finish essays for things on other topics, there’ll still be a few of those. And I’m not going to go around deleting already written Big Finish essays. But starting with Volume 8, none of the new essays added to any of the book collections are going to be on Big Finish material.

As it’s come up a few times and I’ve thus far only said it on Twitter, I figured I should make a quick statement on the site. Short form: I have decided going forward that I will no longer be covering Big Finish material on the site or in my books. There are a handful of existing obligations I’ll still fulfill. I’ve promised Andrew Hickey I’ll cover Doctor Who and the Pirates in the revised Volume 6, and while I’m going to swap out one or two of the mooted 7th Doctor Big Finish essays for things on other topics, there’ll still be a few of those. And I’m not going to go around deleting already written Big Finish essays. But starting with Volume 8, none of the new essays added to any of the book collections are going to be on Big Finish material.

being “about the coincidences that happen to all of us all of the time. We can all recall instances when we have been thinking about a particular person and then have met a friend who — totally unprompted — will begin talking about that person.” She more or less paraphrases this in the song, referring to “a day of coincidence with the radio.” Texts are a source of coincidence as well, such as when “you pick up a paper/you read a name/you go out/it turns up again and again.” There’s a sense Bush is being haunted by text, that the spoken word will accompany her wherever she goes. This is where Bush differs most radically from, say, Burroughs or Foucault, in that this constant presence of language and strangeness is a comfort to her, something to tip her hat to.…

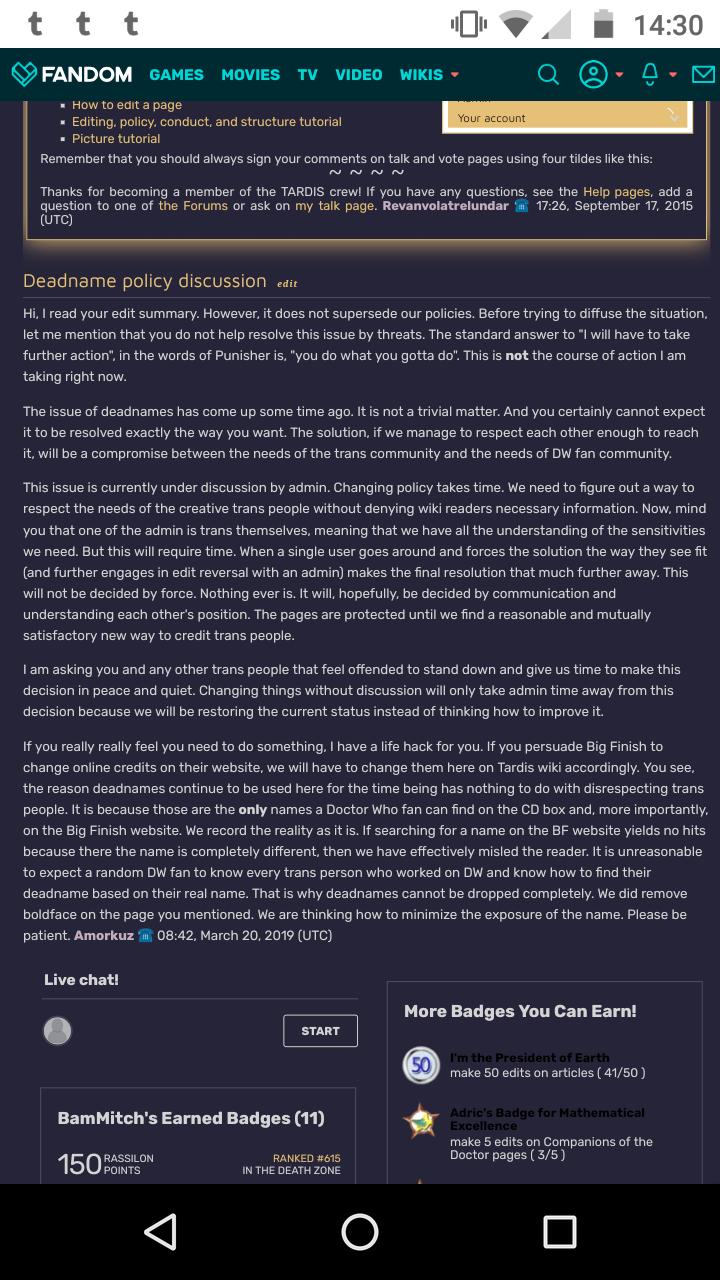

being “about the coincidences that happen to all of us all of the time. We can all recall instances when we have been thinking about a particular person and then have met a friend who — totally unprompted — will begin talking about that person.” She more or less paraphrases this in the song, referring to “a day of coincidence with the radio.” Texts are a source of coincidence as well, such as when “you pick up a paper/you read a name/you go out/it turns up again and again.” There’s a sense Bush is being haunted by text, that the spoken word will accompany her wherever she goes. This is where Bush differs most radically from, say, Burroughs or Foucault, in that this constant presence of language and strangeness is a comfort to her, something to tip her hat to.… When another editor attempted to follow up on this decision, they got the reply shown to the right here.…

When another editor attempted to follow up on this decision, they got the reply shown to the right here.… In this episode we touch on the promised topic of the mainstreamers vs the vanguardists in the far-right movement, but only in the course of covering topical events.

In this episode we touch on the promised topic of the mainstreamers vs the vanguardists in the far-right movement, but only in the course of covering topical events.