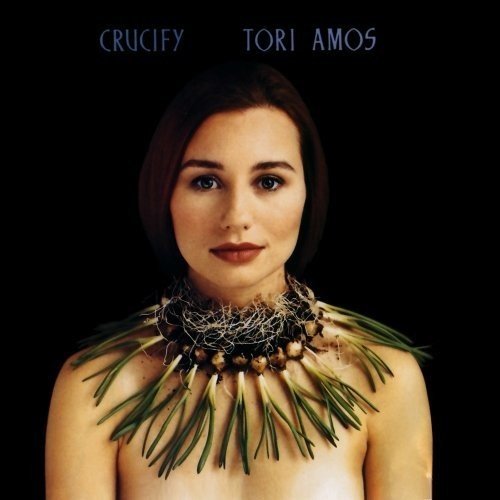

An Empty Cage Girl (Crucify)

Crucify (TV performance, 1991)

Crucify (Top of the Pops, 1992)

Crucify (TV performance, 1992)

Crucify (TV performance, 1993)

Crucify (TV performance, 1999)

Crucify (TV performance, 2002)

Crucify (official bootleg, 2007, Tori set)

Crucify (radio performance, 2009)

Graveyard/Crucify (TV performance, 2015)

There is a teenage girl, though she doesn’t know it. I don’t remember how she came to Little Earthquakes. More likely than not, it was recommended to her by someone at CTY, the academic summer camp she went to and met all the other awkward teen weirdo nerds, no small portion of which, it turned out, were self-closeted queers just like her. That or she just saw mention of Tori Amos online in discussions of other music she was into, which, alongside a smattering of the contemporary alternative scene, was mostly female singer-songwriters.

Sitting in her bed, she presses play on the CD. It’s immediately clear that Amos fit the bill of her taste. But it’s just as immediately clear that there was more to this than merely being “her thing.” The first forty-five seconds of “Crucify” are an exercise in quiet tension. Like “Take to the Sky,” it opens with a series of open fifths on the piano, this time played individually between kicks of a drum. The drum adds a sense of ominous weight, while the chords, in their solitude, sound hollow and anxious without their thirds. The song moves swiftly into its prechorus, where the piano begins a bunch of yearning runs that seem to climb up towards some higher ground before breaking and receding.

The girl does not consciously notice any of this. Her hands burnt by childhood Catholicism, by fourteen she’s become an atheist with neopagan sympathies. Like her gender, these are not a thing she thinks to express. Her parents don’t want a rebellious daughter; they don’t even want a rebellious son. In a year or two, she will come out at school as bisexual, get outed to her parents when someone called the house to rat her out, and be told flatly by her mother, “no you aren’t.” When that’s all that being yourself was going to get you, what’s the point of figuring out who that was?

So obviously what draws her attention are the lyrics. The verse’s description of anxiety and public castigation resonates with her less than it someday will, but the prechorus is something else entirely. “I’ve been looking for a savior in these dirty streets / looking for a savior beneath these dirty sheets.” She isn’t sure what exactly has arrested her. Subsequent efforts at analysis will unpick why the lines work—the way in which Amos uses wordplay to anchor a sharp turn between a relatively standard Christian image of finding god in materially impoverished places and an image that’s implicitly rooted in a rigorously unglamorous sense of the carnal. It might even be that simple for her, though still doesn’t know to phrase it that way. I suspect, however, that it’s at once simpler and more nuanced than that—that what enraptures her so is simply the underlying sense of taboo, not just in the juxtaposition of the divine with a post-coital bed, but in a presentation of sex that’s framed entirely in terms of female agency, that’s unromanticized, messy, even unerotic, but, crucially, that’s still firmly and unequivocally sacred.

And then the chorus. Oh, the chorus. Anchored by the drum kicking up to the quarter notes, it resolves the building tension by stepping up into anthemic force. And yet the lyrics are anything but empowering, with Amos demanding to know “why do we crucify ourselves / every day I crucify myself / nothing I do is good enough for you.” Only the end of the chorus offers anything beyond this self-excoriation, as she makes a tentative step at reclamation by declaring that “my heart is sick of being in chains,” the last word stretched out into a soaring ten syllable vocal run.

And then the chorus. Oh, the chorus. Anchored by the drum kicking up to the quarter notes, it resolves the building tension by stepping up into anthemic force. And yet the lyrics are anything but empowering, with Amos demanding to know “why do we crucify ourselves / every day I crucify myself / nothing I do is good enough for you.” Only the end of the chorus offers anything beyond this self-excoriation, as she makes a tentative step at reclamation by declaring that “my heart is sick of being in chains,” the last word stretched out into a soaring ten syllable vocal run.

The girl does not know what, exactly, she is feeling. There is not actually language to describe most of what she is feeling. She has peered over the precipice into a cavernous possibility—a mode of being she had not imagined sufficiently to want. Blasphemy and sacredness and sex and trauma and so much more swirl together into an incomprehensible incandescence that she recognizes even though she’s never seen anything like it before—a searing and intimate knowledge of womanhood that will take twenty years for her to even begin to fully grasp the consequences of. There are other songs that will plunge her into this fecund abyss—even ones on this album. But with “Crucify,” something impossible begins.

She is, of course, scarcely alone in this. The contours of her awakening are as unique as anyone’s, but “Crucify” was relentlessly and carefully designed to do something very much like what it did for her. Positioned at the top of the album, it was clearly designed to be the main single even as the UK got a bevy of other songs first, and the US got “Silent All These Years” as an initial promotional single. It’s the song on Little Earthquakes to get the most straightforward pop production—drop it into a playlist of alternative rock hits from the period and it fits in a way that none of the other singles do. (Ironically, this also means that it’s the song on the album one can most easiy imagine a Y Kant Tori Read version of.) This is also clearly something that was labored on, with the album version (produced in the first block of recording with Davitt Sigerson) getting a rework by Ian Stanley for the single to fine-tune the instrumentation. (This is in practice something of a wash—Stanley brings the piano forward in the chorus, which gives it newfound sweep and majesty, but he does this by eliminating the bass drum that anchors Sigerson’s version, leaving the verses feeling feeble in comparison.) And these efforts paid off—the song notched the album’s highest chart placing, making it to 22nd in the US Alternative charts, and 15th in the UK charts.

Atlantic was similarly involved in the details on the video, although this had altogether more mixed results, with director Cindy Palmano walking away from the edit over the difference between visions. Her contributions focused on a carefully structured sequence in which we watch Amos through a narrow vertical slit, catching glimpses as she dons an elaborate Anne Boelyn-inspired outfit, followed by a series of shots in which she walks imperiously to a bathtub, immerses herself in it, and finally dances wearing the outfit. Amos, on the commentary track for the video, weaves all of this into a characteristically striking account of Anne Boelyn as “the illicit mistress of the Protestant Reformation” and of her needing “to rebaptize myself as a woman that is independent of the doctrine that I had been… let’s say immersed in as a young girl.” (Palmano also shot material in which shots of Amos in a short blue dress share the screen with each other, which Amos helpfully explains by saying, “I’ve always had a thing for waitresses, and I thought we needed some cheerleaders.”)

Atlantic, meanwhile, added a sequence in which Amos, clad in tight jeans and a matching top and with fulsome makeup, plays the song on piano. This material leans hard into the sexualization of a woman playing the piano, with Amos swaying on the piano bench and grinding her hips into it. Palmano is not wrong to describe it as “dreadful” and “an obvious approach to femininity,” but there’s also no point in denying that the dynamic is a substantial part of Amos’s public image. This has its plusses and minuses, the latter being largely comprised of YouTube comments on her live performances in which various people discover their human furniture fetishes in real time, but it’s absolutely a dynamic that Amos plays mindfully with, and while Atlantic can fairly be accused of cynicism in making sure it was foregrounded in the video, it’s not fair to pretend that the move didn’t contribute to “Crucify” succeeding as an initial portal into Tori Amos’s artistic vision.

Atlantic, meanwhile, added a sequence in which Amos, clad in tight jeans and a matching top and with fulsome makeup, plays the song on piano. This material leans hard into the sexualization of a woman playing the piano, with Amos swaying on the piano bench and grinding her hips into it. Palmano is not wrong to describe it as “dreadful” and “an obvious approach to femininity,” but there’s also no point in denying that the dynamic is a substantial part of Amos’s public image. This has its plusses and minuses, the latter being largely comprised of YouTube comments on her live performances in which various people discover their human furniture fetishes in real time, but it’s absolutely a dynamic that Amos plays mindfully with, and while Atlantic can fairly be accused of cynicism in making sure it was foregrounded in the video, it’s not fair to pretend that the move didn’t contribute to “Crucify” succeeding as an initial portal into Tori Amos’s artistic vision.

Ironically, however, all of this works in part precisely because “Crucify” is atypical for Amos. With the exception of the second verse (which, with the “cat named Easter” section, has the song’s best lyric), the song steers away from the idiosyncrasies of Amos’s personal mythology in favor of something much more direct and declarative. Like “Take to the Sky,” it seems very much like a song Amos had to get out and get past, with the final declaration that she’s “never going back again / crucify myself again” marking a genuine personal milestone that she subsequently lived by.

But even within Amos’s worldview, the song is odd. “Crucify” is clearly, among other things, Amos grappling with her own Christian upbringing—she says as much in the video commentary. But her upbringing was decidedly Protestant, whereas “Crucify’’s concerns run much more Catholic (the Catholic church being the ones who are most inclined to focus on the act of crucifixion by depicting Christ’s actual body on the cross, where Protestants prefer the more abstract symbol of the cross itself than the actual bodily suffering endured upon it). This is easy enough to explain—Amos’s apartment at the time was behind a Catholic church, a fact she mentions frequently when talking about the songs on the album. But it’s still a clear idiosyncrasy.

The practical effects of the shift are largely subtle, coming down to the difference between guilt and shame, and ultimately “Crucify” resonates with both sides of this dichotomy (“nothing I do is good enough for you” leans more guilt, while “my heart is sick of being in chains” points more towards shame’s focus on repression before the fact than guilt’s reflective approach to self-hatred). But the point ultimately isn’t precisely where in the spectrum of repressive Christian worldviews “Crucify” lands, but rather the fact that it successfully splits the difference. In marked contrast to the inscrutable singularity of most of her work, “Crucify” is scrupulously accessible, using that classic pop music trick of writing so that any listener can project themselves into the song. It’s not a song that showcases Amos’s best talents. But as I learned, it’s a vividly effective gateway to them.

Recorded in Los Angeles at Capitol Records in 1990, produced by Davitt Sigerson. Single mix produced by Ian Stanley. Video directed by Cindy Palmano. Played live throughout Amos’s career.

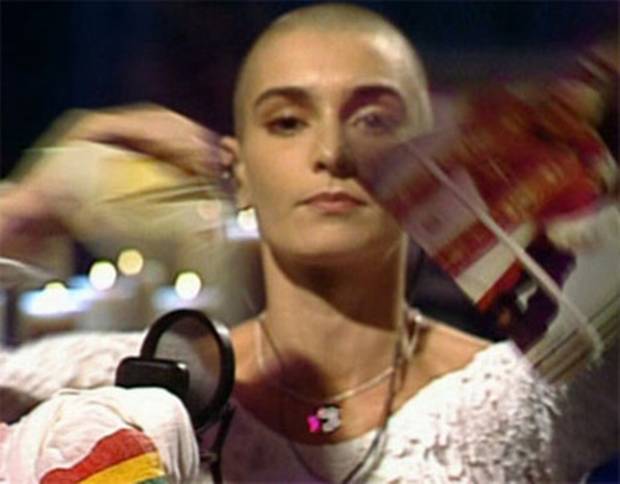

From top: Sinead O’Connor rips the Pope on Saturday Night Live, “Crucify” single, still from “Crucify” video

Crucify (live, 1991)

Crucify (live, 1991)

October 16, 2019 @ 9:57 pm

When that’s all that being yourself was going to get you, what’s the point of figuring out who that was?

On a possibly related note, back around 1990 when he still had hair on a regular basis, Grant Morrison did an interview for the late, lamented Amazing Heroes in which he summarized the train journey that had inspired his mini St Swithin’s Day more or less thusly: “I went from Glasgow to Penzance to find myself and realised that I hadn’t been looking for. So I went home.”

(This interview is also notable for being the first place I, for one, ever heard of Captain Clyde.)

October 25, 2019 @ 9:38 am

if you want escort services around you and feel be like secure than visit our site

October 25, 2019 @ 9:39 am

Nice article. have very informative content and thanks for sharing

October 25, 2019 @ 9:41 am

nice post….

January 27, 2020 @ 10:58 am

Nice piece. Have very insightful content and thank you for sharing your details

January 27, 2020 @ 11:00 am

Good article. Have very insightful content and thank you for sharing the information

https://sysqoindia.com/

October 8, 2020 @ 7:24 am

Nice article. have very informative content and thanks for sharing

November 4, 2020 @ 9:35 am

Bermain poker online kini sudah bisa dengan berbagai cara, salah satunya adalah IDN Poker Deposit Pulsa yang memberikan game poker terbaik, dengan cara deposit melalui pulsa handphone anda. yuk ikuti langkah – langkah mudah deposit mudah di http://nolinfoundation.com/situs-judi-idn-poker-deposit-pulsa-terbaik-di-indonesia/