Butterflies Don’t Belong in Nets (Mary)

Mary (2007, official bootleg, Clyde set)

Let’s begin on January 11th, 1967, in London, where the Jimi Hendrix Experience went into the studio and to cut “Purple Haze.” With twenty minutes left in the session, they decided to cut a quick demo of a newly written song as well, “The Wind Cries Mary.” Written by Hendrix following a screaming fight with his then-girlfriend Kathy Etchingham (Mary being her middle name, which Hendrix would use to annoy her) over whether her mashed potatoes were too lumpy, the song is a downbeat R&B number with lyrics that can be best described as a sad man’s psychedelic whinge.

A quarter-century later, Tori Amos stepped into a Capitol Records studio with Davitt Sigerson to pen a response of sorts. “Mary” is no straightforward response song reimagining events from Etchingham’s perspective—indeed it’s not even about her in any sense. Nor is it hostile to Hendrix to any real degree—he’s invoked on a chummy first-name basis in the second part of the chorus by way of reassuring the eponymous Mary that “even the wind cries your name.”

Amos, instead, is reaching for what will become one of the wellsprings of her work: the reclamation of the feminine divine. The lyric is gnomic—a wandering piece that repeatedly circles back to the ecological, both in the first verse (“lush valley all dressed in green / just ripe for the picking”) and the second (“rivers of milk are running dry / can’t you hear the dolphin’s crying / what’ll we do when our babies scream / fill their mouths with some acid rain”). Who exactly the Mary that Amos calls upon is vague—there’s no direct Christian imagery, but the name carries enough totemic power that there doesn’t have to be.

Indeed, Amos ends up playing an ambiguity in the space left by the lack of description—the default Mary is the Virgin Mary, but Amos is just as likely to be referring to Mary Magdalene. Indeed, in multiple 2003 interviews around the release of Tales of a Librarian (which featured a rerecorded version of “Mary”) Amos talked about the need “to marry the two Marys together.” And the lyrics certainly lean a little more Magdalene than Virgin in their vagueness, most obviously in the lines “Las Vegas got a pin-up girl / they got her armed as they buy and sell her,” which clearly evokes something adjacent to Mary Magdalene’s traditional (albeit unattested in the actual Bible) role as a prostitute. (The debate is ultimately settled in the compilation’s liner notes, which engage in the amusing game of filing the songs according to the Dewey Decimal System. There, “Mary” is cross-listed in 363.7:Social Problems and Social Services—Abuse of the Earth and 226:The Bible—Mary Magdalene.)

Ultimately, however, the song is more vague than quite works. The dualistic Mary leaning towards Magdalene is an interesting and well-supported read, but it ultimately doesn’t provide much useful insight for a song that swerves from bemoaning the objectification of women into a verse about acid rain without really filling in any of the space between those two concepts. Mary Magdalene reimagined as a wronged nature goddess is a phenomenal idea, but one that needs more execution than Amos gives it. Amos will get to the point where she can do things like this straightforwardly enough, but “Mary” mostly feels like what it is—a tentative first stab whose whole is rather shy of the sum of its parts.

Things aren’t entirely helped by the production. The Sigerson sessions were a vital step in a smoldering war between Amos and Atlantic. Amos had played label head Doug Morris some demos and had gotten an exacerbated reception in which he demanded that, as a piano player, she write him the next “Rocket Man.” And so Atlantic sent her Davitt Sigerson, fresh off of producing “Eternal Flame” for the Bangles. Sigerson’s brief was to get Atlantic’s unruly piano lady in line. Instead, Sigerson went rogue, deciding that Amos both knew what kind of musician she was and was good at being that musician. Sigerson told Amos to stop trying to fit her album to expectations, instead telling her that she should “fit everything else around you and your music and people will come to terms with it because this is great and should not be changed.” And so the Sigerson tracks made a point of building up from Amos’s vocal and piano takes, fitting the rest of the instrumentation around it.

All of which is a lead-up to the observation that “Mary” demonstrates this approach in its failures. You can see how it was put together—it’s a simple arrangement in which Amos’s piano is backed by a propulsive drum that’s counting off the two and four beats. The drum gives a classic rock vibe to the song that’s fitting given the Hendrix shout-out, but it’s also a blunt instrument, bludgeoning the song into submission, and its gradual crescendoing over the song as Amos produces an increasingly over the top vocal performance (lowlights include the crashing bathos of “fill their mouths with acid rain” and a whisper-shouted “can you hear me” in the chorus after the bridge) ends up being faintly exhausting over four and a half minutes.

And so in 2003, while putting together her first compilation, Tales of a Librarian, Amos decided to do a new recording of “Mary” with her by then standard set of musicians. This version takes a slower and more understated approach, avoiding the sense of each new line as an attack. The result is more methodical and lacks any overt flaws in the arrangement, but ultimately serves to reveal the limitations of the underlying song in a way that the Sigerson version does not. Ultimately the song is a rough stab at the sort of wrestling with god and spirituality that Amos wants to do. She’ll do far better—indeed, she did far better during the Sigerson sessions for Little Earthquakes.

Recorded in Los Angeles at Capitol Records in 1990, produced by Davitt Sigerson, and released on the “Crucify” single in the UK. Re-recorded in Cornwall at Martian Engineering in 2003, produced by Tori Amos. Played on various tours, most substantially in 2003, but largely retired after 2007.

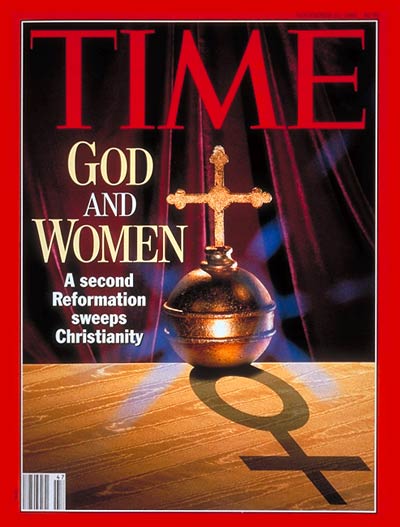

Top: November 23rd, 1992 cover of Time

Mary (1992)

Mary (1992)

October 11, 2019 @ 9:33 am

This is certainly useful. Very beneficial for me.