Chapter Three: The Unique Details and Methods of a Crime (The Judge of All The Earth)

Part of the difficulty in tracking the fallout of Moore’s split with DC is simply that it’s so extensive. Once the rupture began it spread quickly, fueled in no small part by Alan Moore’s tendency to, as he’s put it, burn his bridges when reacting against something so as to make sure he’s never tempted to go second guess himself. But in this case the fractal repetition of Moore’s grievances with DC have served to make the initial issues harder to see, to the point where the standard wisdom is that Moore’s break with DC came over a dispute in the handling of the Watchmen trade paperback when, in reality, he had made his decision not to accept any new work from DC in January of 1987, eight months before the trade paperback even came out, and five months before Moore was actually done working on it. This decision came during a wider dispute about DC’s proposed creation of a ratings system for their comics. And even that point is not a single discrete cause that can be separated out from all of the others and identified as the original, true rift, but at best the third issue to arise between Moore and DC in quick succession.

Part of the difficulty in tracking the fallout of Moore’s split with DC is simply that it’s so extensive. Once the rupture began it spread quickly, fueled in no small part by Alan Moore’s tendency to, as he’s put it, burn his bridges when reacting against something so as to make sure he’s never tempted to go second guess himself. But in this case the fractal repetition of Moore’s grievances with DC have served to make the initial issues harder to see, to the point where the standard wisdom is that Moore’s break with DC came over a dispute in the handling of the Watchmen trade paperback when, in reality, he had made his decision not to accept any new work from DC in January of 1987, eight months before the trade paperback even came out, and five months before Moore was actually done working on it. This decision came during a wider dispute about DC’s proposed creation of a ratings system for their comics. And even that point is not a single discrete cause that can be separated out from all of the others and identified as the original, true rift, but at best the third issue to arise between Moore and DC in quick succession.

There are of course two ways to look at this. In one, the subsequent retellings of the dispute on both sides have thoroughly muddied the waters such that the original dispute over comics ratings has been obscured. And there’s a degree of truth to this – the latter focus on the rights to Watchmen and DC’s broader exploitation of the property has largely eclipsed what was a real and acrimonious dispute in the early months of 1987. In the other, however, it is the wider perspective that looks at the full extent of Moore’s myriad of grievances that is more accurate, even about the initial dispute. In this view, just because the rating’s system was the straw that broke the camel’s back doesn’t mean that the bale of hay as a whole wasn’t the cause. And this view has a wider support within Moore’s career, which by the start of 1987 was already characterized by a string of disputes with his publishers. Indeed, by the time Watchmen started Moore had already broken with all of his UK publishers, although his departure from IPC had not yet taken on the tone of finality that his rifts with Marvel UK and Dez Skinn had. Indeed, if one wanted to be unsympathetic to Moore – and it’s worth stressing that there are no shortage of people who are very much invested in being more or less completely unsympathetic to Alan Moore – one could suggest that getting into fights with his publishers was simply what he did, and that he was, consciously or unconsciously, just looking for a reason to get mad at DC.

Certainly Moore would have had little reason to see DC as essential to his career. He had, after all, succeeded with essentially every company he’d worked with.…

Certainly Moore would have had little reason to see DC as essential to his career. He had, after all, succeeded with essentially every company he’d worked with.…

This is, perhaps, why so much ink has been spilled within the War on attempts to argue that this gap, in effect, does not exist – that Watchmen can be understood purely, or at least primarily, in terms of its influences, thus allowing those living in its wake to exist as though they are free from its vast and monolithic splendor. It is, after all, the easier option; it does not require staring too long at the cavernous depths within. It gives the comforting illusion that Watchmen is, at its heart, an easily solved mystery – a question with a definite answer. Nothing could be further from the truth, but for those who would otherwise find themselves caught in its blast, reduced to mere shadows cast by its incinerating radiance the idea that the book is simply some inevitable consequence of what came before is a useful delusion.

This is, perhaps, why so much ink has been spilled within the War on attempts to argue that this gap, in effect, does not exist – that Watchmen can be understood purely, or at least primarily, in terms of its influences, thus allowing those living in its wake to exist as though they are free from its vast and monolithic splendor. It is, after all, the easier option; it does not require staring too long at the cavernous depths within. It gives the comforting illusion that Watchmen is, at its heart, an easily solved mystery – a question with a definite answer. Nothing could be further from the truth, but for those who would otherwise find themselves caught in its blast, reduced to mere shadows cast by its incinerating radiance the idea that the book is simply some inevitable consequence of what came before is a useful delusion.

It’s September 30

It’s September 30 It’s November 26th, 1977. Between now and December 17th, an airplane carrying the University of Evansville basketball team will crash, killing the entire team, another plane crash at Madeira Airport in Portugal kills a hundred and thirty-one, and sex worker Marilyn Moore is injured in an attack by the Yorkshire Ripper. Despite the relative paucity of major disasters, the world still creeps ever closer to the eschaton and The Sun Makers airs.

It’s November 26th, 1977. Between now and December 17th, an airplane carrying the University of Evansville basketball team will crash, killing the entire team, another plane crash at Madeira Airport in Portugal kills a hundred and thirty-one, and sex worker Marilyn Moore is injured in an attack by the Yorkshire Ripper. Despite the relative paucity of major disasters, the world still creeps ever closer to the eschaton and The Sun Makers airs. It is impossible to talk about The Deadly Assassin without getting into the weeds of Doctor Who continuity, a sentence that is arguably the most depressing thing yet written in this project. Phil Sandifer manages to belch forth nearly 13,000 words of typically fanciful speculation (although at least this time he manages to avoid anything quite so masturbatorily pat as “the Doctor is from the Land of Fiction,” a critical conclusion so sickeningly self-congratulatory that it’s no wonder its author has disappeared off the face of the Internet and indeed the planet), but he’s hardly alone. Vast swaths of what Doctor Who gets up to when its worst instincts are indulged—waffle about the Eye of Harmony, Rassilon, Shabogans, and indeed Gallifreyan lore in general—all find their origin point here.

It is impossible to talk about The Deadly Assassin without getting into the weeds of Doctor Who continuity, a sentence that is arguably the most depressing thing yet written in this project. Phil Sandifer manages to belch forth nearly 13,000 words of typically fanciful speculation (although at least this time he manages to avoid anything quite so masturbatorily pat as “the Doctor is from the Land of Fiction,” a critical conclusion so sickeningly self-congratulatory that it’s no wonder its author has disappeared off the face of the Internet and indeed the planet), but he’s hardly alone. Vast swaths of what Doctor Who gets up to when its worst instincts are indulged—waffle about the Eye of Harmony, Rassilon, Shabogans, and indeed Gallifreyan lore in general—all find their origin point here. It’s October 25th, 1975. Between now and November 15th

It’s October 25th, 1975. Between now and November 15th It’s January 25th, 1975. Between now and February 15th, Edward Wilson and Robert McCullough will both die in attacks in Belfast, Clyde Hay will be the final viction of the Skid Row Slasher, a hundred and three civilians will be slaughtered by Ethiopian troops in Woki Duba, and two thousand and forty one will die in an earthquake in China. In addition, CEO of United Brands (formerly United Fruit) Eli M. Black will commit suicide shortly before it emerges that he paid a large bribe to the President of Honduras, P.G. Wodehouse will die of a heart attack in a hospital in Long Island, and Richard Ratsimandrava, the recently installed President of Madagascar, will be assassinated, sparking a civil war. Also, the world will slide ever closer to the eschaton, and The Ark in Space will air.

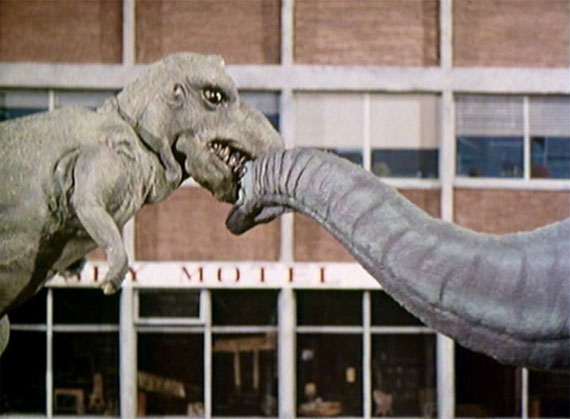

It’s January 25th, 1975. Between now and February 15th, Edward Wilson and Robert McCullough will both die in attacks in Belfast, Clyde Hay will be the final viction of the Skid Row Slasher, a hundred and three civilians will be slaughtered by Ethiopian troops in Woki Duba, and two thousand and forty one will die in an earthquake in China. In addition, CEO of United Brands (formerly United Fruit) Eli M. Black will commit suicide shortly before it emerges that he paid a large bribe to the President of Honduras, P.G. Wodehouse will die of a heart attack in a hospital in Long Island, and Richard Ratsimandrava, the recently installed President of Madagascar, will be assassinated, sparking a civil war. Also, the world will slide ever closer to the eschaton, and The Ark in Space will air. It’s January 12th, 1974. Between now and February 16th, twelve people will die in an IRA bmombing of a coach bus on the M62, and a hundred and seventy three people will die in a fire in Sāo Paulo. The implementation of the three-day week will cause massive economic strain on the United Kingdom, which does not directly kill anybody, but is linked to large spikes in crime and mental illness. In addition, Batman creator Bill Finger will die of a heart attack and movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn will die of old age. Beyond that, the world moves ever closer to the eschaton and Invasion of the Dinosaurs airs on the BBC.

It’s January 12th, 1974. Between now and February 16th, twelve people will die in an IRA bmombing of a coach bus on the M62, and a hundred and seventy three people will die in a fire in Sāo Paulo. The implementation of the three-day week will cause massive economic strain on the United Kingdom, which does not directly kill anybody, but is linked to large spikes in crime and mental illness. In addition, Batman creator Bill Finger will die of a heart attack and movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn will die of old age. Beyond that, the world moves ever closer to the eschaton and Invasion of the Dinosaurs airs on the BBC.