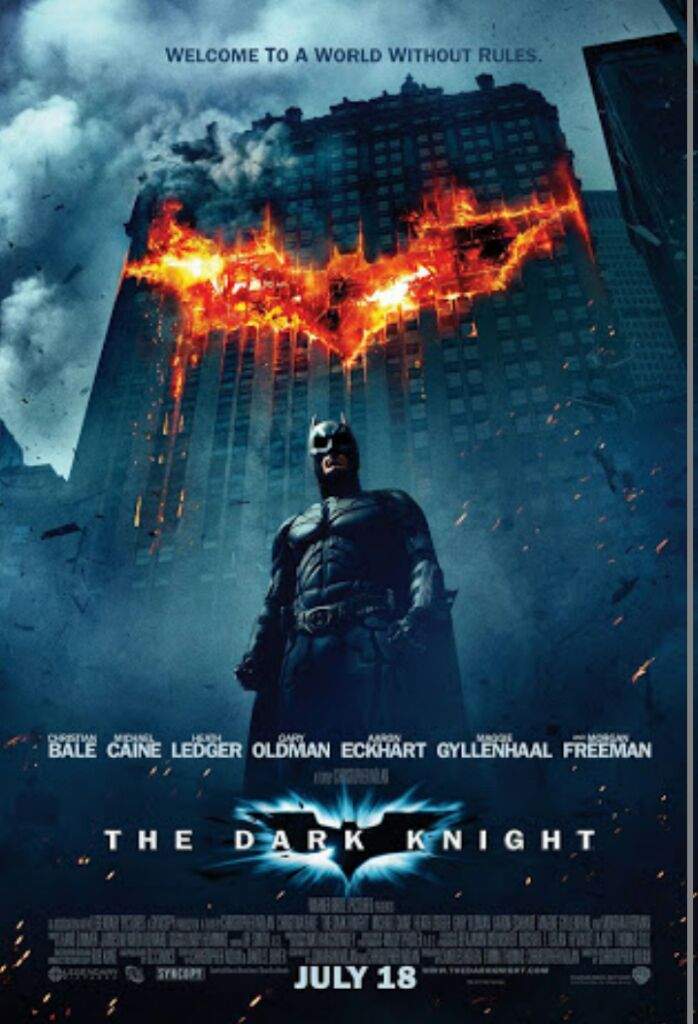

An Accurately Named Trilogy II: The Dark Knight

It seems silly to start anywhere besides the Joker. We’ll set aside the cynical but not entirely unfounded question of whether the performance would be as celebrated as it is were it not for Heath Ledger’s untimely death and the ghoulish speculation (since refuted) that the psychological intensity of the role was a cause. Sure, it’s tough to imagine a Batman film winning an acting Oscar under less tragic circumstances, but that’s in no way what’s interesting here. What’s interesting is that Ledger and Nolan took the most oversignified character in Batman mythos (and yes, of course I’m including the big rodent himself) and offered a game-changing take on him. The hunched, disheveled figure with a Glasgow smile is a new angle, skewing the Joker towards a materialism that is generally precisely what’s discarded in other efforts to make him more grandiosely crazy. Ledger and Nolan offered a new way for the Joker to be.

It seems silly to start anywhere besides the Joker. We’ll set aside the cynical but not entirely unfounded question of whether the performance would be as celebrated as it is were it not for Heath Ledger’s untimely death and the ghoulish speculation (since refuted) that the psychological intensity of the role was a cause. Sure, it’s tough to imagine a Batman film winning an acting Oscar under less tragic circumstances, but that’s in no way what’s interesting here. What’s interesting is that Ledger and Nolan took the most oversignified character in Batman mythos (and yes, of course I’m including the big rodent himself) and offered a game-changing take on him. The hunched, disheveled figure with a Glasgow smile is a new angle, skewing the Joker towards a materialism that is generally precisely what’s discarded in other efforts to make him more grandiosely crazy. Ledger and Nolan offered a new way for the Joker to be.

By some margin the least interesting parts of this are the most often remarked upon. Yes, Ledger’s schlubby maniac was an easier fit for a certain strain of geek masculinity than the more overtly queer portrayals that came before him. But frankly, anybody who needed reassurance that the Joker’s makeup was “like warpaint” before they’d dress as him for Halloween needs to be fired into the sun. “Why so serious” is a great marketing line, but it’s a trivial part of the character’s personality – a line he uses in one of the mutually contradictory origin stories he gives – and reducing Ledger’s take to his leering transgressiveness is how you get Jared Leto’s performance in Suicide Squad.

To understand what’s going on with Ledger’s Joker, it’s necessary to understand the basic oversignification of the character. For that, let’s turn fleetingly to what is both the best comic story written about him and the low point of Alan Moore’s career, Batman: The Killing Joke. (This being where Nolan’s “multiple contradictory origins” idea originates.) For all that Moore crafts a typically symbolically rich take on the Joker, the big problem with the story, as Moore readily admits, is that he didn’t define the Joker as anything other than Batman’s archnemesis. He represents nothing save for a particular limit point for Batman – an irreducible reality of his mythos interesting for few reasons other than that homicidal clowns with good visual design are kinda cool.

This is not what the Joker in The Dark Knight is doing, although it’s easy to miss that fact. The centrist liberalism that is the default setting of most popular culture means that we’re most used to villains who are cuddly versions of fascism: Voldemort, the Empire, the Daleks, etc. It’s easy to make too much of this – the defanged fascists of popular culture villainy are generally so cartoonishly that if they have any political effect, it’s to blind us to fascists that don’t literally call themselves Death Eaters, have the Imperial March as their theme song, or shriek “EXTERMINATE” a lot.…

At long last, there’s a new volume of

At long last, there’s a new volume of  MIZUMONO: Dessert. Unlike savoureux, mizumono is in fact sweet, suggesting that the show has allied itself with Hannibal’s perspective as opposed to Will’s.

MIZUMONO: Dessert. Unlike savoureux, mizumono is in fact sweet, suggesting that the show has allied itself with Hannibal’s perspective as opposed to Will’s.

TOME-WAN: A miso or vegetable soup with rice. This signifies nothing more than the approaching end of the meal.

TOME-WAN: A miso or vegetable soup with rice. This signifies nothing more than the approaching end of the meal.

KŌ NO MONO: An assortment of pickled vegetables. Janice Poon suggests that this signals the approaching denouement, and also makes a nice metaphor about the vegetables sharpening the senses, which is what Alanna needs. The reality is that the second season is not so much going off the rails as plummeting down the gorge, watching mournfully as the rails disappear into the sky.

KŌ NO MONO: An assortment of pickled vegetables. Janice Poon suggests that this signals the approaching denouement, and also makes a nice metaphor about the vegetables sharpening the senses, which is what Alanna needs. The reality is that the second season is not so much going off the rails as plummeting down the gorge, watching mournfully as the rails disappear into the sky.

NAKA-CHOKO: A citrusy soup, used as a palate cleanser. Hannibal does suggest that a meat has citrus notes, but that’s a stretch. Not even Janice Poon tries to explain this one.

NAKA-CHOKO: A citrusy soup, used as a palate cleanser. Hannibal does suggest that a meat has citrus notes, but that’s a stretch. Not even Janice Poon tries to explain this one.

SHIIZAKANA: A hot pot dish, meat-based and the nominal main course. I’m going to go ahead and just call it “no relation” to the contents of the episode, because reading this as somehow forming a culminating centerpiece of the season is just too ridiculous.

SHIIZAKANA: A hot pot dish, meat-based and the nominal main course. I’m going to go ahead and just call it “no relation” to the contents of the episode, because reading this as somehow forming a culminating centerpiece of the season is just too ridiculous.

SU-ZUKANA: A palate cleanser, typically involving vinegar. A better title for last week, I suspect, but still fitting for this, which essentially starts off with all new concerns.

SU-ZUKANA: A palate cleanser, typically involving vinegar. A better title for last week, I suspect, but still fitting for this, which essentially starts off with all new concerns._001-031.jpg) Let’s give the Proverbs a week off and talk about

Let’s give the Proverbs a week off and talk about