Ordinary Torture (Book Three, Part 66: The CIA)

Content warning: Images of physical mutilation

Previously in Last War in Albion: Joyce Brabner, after getting into the world of comics by becoming a major figure in Harvey Pekar’s autobiographical comic American Splendor (and marrying Pekar in the process), is contacted by the Christic Institute, run by Daniel Sheehan, a lawyer who came to prominence during the Karen Silkwood case.

You’re tuning it out. I can see your ocular focus shifting. You’ve been trained to handle interrogation, in a very specific way. I bet you can even bypass ordinary torture. And none of these people picked it u. Because DHS is formed out of sixteen domestic agencies. And you’re from the Central Intelligence Agency. – Warren Ellis, Jack Cross

Silkwood’s family ultimately sued Kerr-McGee for negligence in the original plutonium poisoning, successfully recovering $1.38 million dollars in a settlement; Sheehan was among the attorneys in the case, and founded the institute in the wake of their success to pursue similar cases, using civil suits to right wrongs that the criminal justice system had proved inadequate for.

This was often a successful strategy—in one of their early cases, for instance, the Institute represented survivors of the Greensboro massacre, in which white supremacists shot and killed five participants in a “Death to the Klan” rally. State and federal prosecutions failed to secure any convictions, and so the Christic Institute led a successful civil suit to secure justice. But it is important to stress the degree to which the Christic Institute’s strategy was also one of public relations. Sheehan was always, in part, a legal impresario, and one who was prone to making sure he was prominently centered in stories about the group. This meant that the Institute could often be a blunt instrument; one media article about it quotes the leader of another public interest group as saying that “Danny Sheehan is to investigating what a depth charge is to sports fishing.” This bluntness would ultimately have significant consequences.

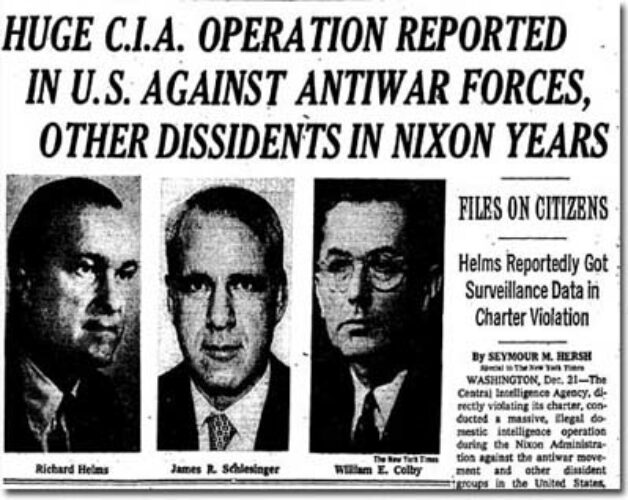

In 1984, the Institute represented Stacey Lynn Merkt, who had been arrested transporting refugees from El Salvador on behalf of the Catholic American Sanctuary Movement. In the course of working this case, Sheehan was visited by multiple religious leaders who repeated claims passed by unnamed government officials that the Sanctuary Movement was in fact smuggling known terrorists into the country. Perturbed by this dedicated misinformation campaign, the Institute began investigating their source, and soon found itself investigating the Central Intelligence Agency.

The Central Intelligence Agency was formed in 1947, in the aftermath of World War II. During the War the US had set up the Office of Strategic Services, its first effort at an intelligence agency. At its head was General “Wild Bill” Donovan, who quickly developed a taste for extravagant covert operations, dropping agents behind enemy lines to commit sabotage or exploring complicated gadgets and tactics—at one point he was investigating how to use bats as a bomb delivery system. In late 1944, Donovan wrote to Franklin Roosevelt arguing for the establishment of a permanent intelligence service.…