What About What I Want? (The Big Picture)

Pictures of You/The Big Picture (live, 2014)

Selected as the lead single and sequenced as the first track, “The Big Picture” serves as the first and, for many, last impression of Y Kant Tori Read. It’s tempting to offer some snark about how unwise this is, but frankly, survey the other options again. There are certainly better songs, but the bulk of them are the downtempo numbers—”Fire on the Side,” “Floating City,” or “Cool on Your Island,” which ended up being the second single. The overblown production and 80s chintz of Y Kant Tori Read is consistently at its worst on the uptempo numbers, which meant that good choices of high energy lead singles were thin on the ground.

Nevertheless, it means that the album opens on a note that borders on self-parody—two bars of rapid, slightly clappy-sounding drums counting off the sixteenth notes in the song’s 128 bpm, followed by a melodramatic synth stab before Amos attempts a swaggering vocal delivery of “someone smashed my window / broke into my brand new car / last night” in a vaguely New Jersey-inflected accent such that it comes out roughly ”someone broke my winduh / broke into my brand new carrh.” Coming at it with any knowledge of Tori Amos, it instantly sells the album’s reputation as an early career embarrassment. On its own terms, it’s a try-hard effort at 80s synth rock that lands squarely in kitsch. Either way, by the fifteen second mark the entire band’s reputation is already set in stone.

And yet “The Big Picture” is not quite bad either. Musically, there are several interesting components. The highlight is a rattling, neurotic guitar line ripped off from John Parr’s “Naughty Naughty.” But the source material also reveals why Y Kant Tori Read’s take on the riff is doomed and gives a preview of most of the poor decisions to come on the album. Parr’s song is in no way good—it’s a swaggering song about pressuring a woman into sex, with an utterly sickening chorus hook of “Don’t tell me ‘I don’t want to be a girl like that’ / do you want to see a grown man cry” delivered over a bunch of bland power cords that finally resolves into the riff from the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me.” But the opening riff that’s used over the verses—the one that Y Kant Tori Read nicks—is in fact fantastic, and the song has the good sense to let it be, giving it four repetitions completely clean as an intro, followed by four more with a simple drum backing before the vocals kick in, and returning to it regularly.

Given that they were stealing it from a minor hit from only four years earlier, it is perhaps understandable that Y Kant Tori Read did not lean quite so hard on the riff. But there’s a vast amount of space between the clean groove of Parr’s original and the cluttered mess of “The Big Picture,” where the line is mixed well behind the vocal, drowned behind a deluge of synths, and moved from the harsh, processed twang of Parr’s tone to an anodyne jangle utterly devoid of personality.…

The Big Picture (1988)

The Big Picture (1988)

…

… Pirates (1988)

Pirates (1988) You Go To My Head (1988)

You Go To My Head (1988) Floating City (1988)

Floating City (1988) On the Boundary (1988)

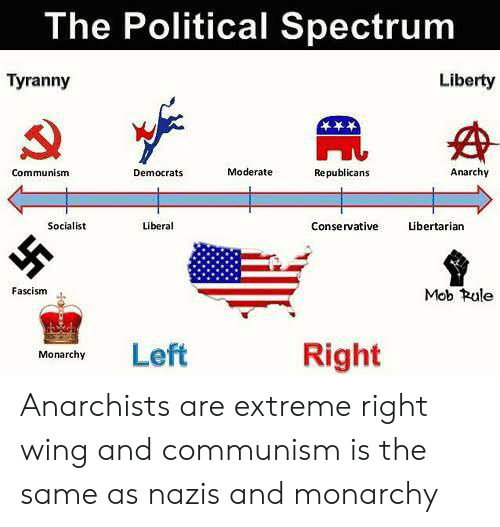

On the Boundary (1988) One of the quintessential aesthetic markers of our current cultural predicament is the online political spectrum. Half pseudo-graph, half meme, it is a largely crude and homemade phenomenon. It is both provocation and ‘cargo cult’ intellectualism. It is especially beloved of the more gonzo elements within the online far-Right. People create these things in their spare time. As ludicrous as they usually are, they represent a tragically doomed attempt by confused and disoriented people (if also often sinister and dangerous ones) to understand a world which seems to them to be increasingly inexplicable, complicated, and menacing. Indeed, they often reveal an attempt to understand a history which is somehow retroactively also becoming more inexplicable, complicated, and menacing. They reveal the scared befuddlement of their makers even as they boastfully claim confident certainty. One of the tragic things about these images is that they show people reaching for a way to express their fuzzy sense of political categories as complex, interrelated, liminal and evolving. They are stunted and flailing attempts to engage in dialectics.

One of the quintessential aesthetic markers of our current cultural predicament is the online political spectrum. Half pseudo-graph, half meme, it is a largely crude and homemade phenomenon. It is both provocation and ‘cargo cult’ intellectualism. It is especially beloved of the more gonzo elements within the online far-Right. People create these things in their spare time. As ludicrous as they usually are, they represent a tragically doomed attempt by confused and disoriented people (if also often sinister and dangerous ones) to understand a world which seems to them to be increasingly inexplicable, complicated, and menacing. Indeed, they often reveal an attempt to understand a history which is somehow retroactively also becoming more inexplicable, complicated, and menacing. They reveal the scared befuddlement of their makers even as they boastfully claim confident certainty. One of the tragic things about these images is that they show people reaching for a way to express their fuzzy sense of political categories as complex, interrelated, liminal and evolving. They are stunted and flailing attempts to engage in dialectics.  Fire on the Side (1988)

Fire on the Side (1988).jpg) Heart Attack at 23 (1988)

Heart Attack at 23 (1988)