The Only Planet That Can’t Conceive You (Floating City)

At first, casual listen, another song of heartbreak and disappointed love: “you went away / why did you leave me / you know I believed you,” it opens. In fact, “Floating City” is the first shot in a longer and larger battle with the patriarchal Christian god of her upbringing. Eventually this would go on to fuel multiple albums in which Amos constructed her own sprawling alternative mythology. Compared to those songs, “Floating City” is a half-developed thought; compared to the rest of Y Kant Tori Read, it’s a song of towering scope and ambition.

Amos is, as she often notes, a minister’s daughter. In some ways this led to all the stereotypes you’d expect. Amos went to church multiple times a week, and sang frequently at weddings and funerals. Her father was reasonably progressive—Amos recounts that he marched with Martin Luther King and was a supporter of women’s rights. But this had clear limits—her account of how after “being exposed to so many gay people who work on my tours and shoots he’s evolved to seeing them as individuals, as people, and not as ‘the gays’” is decidedly modest in its praise. And while he was open-minded enough to chaperone her as she played DC-area gay bars in the late 70s, he also barred music like The Doors and Led Zeppelin from the house, accusing Jim Morrison of being of the Devil. He also embraced the usual sexual repressiveness of American Christianity—Amos describes his ethos as “no short skirts; stay a virgin until you’re married. ‘Gird your loins’ was his favorite saying.”

Even more repressive, however, was her paternal grandmother, Addie Allen Amos, a devoutly religious woman who Amos recalls speaking in tongues on one occasion. It was her grandmother that pushed Amos’s father into ministry, and she was fiercely critical of him afterwards—Amos recounts that she’d “write him letters criticizing his sermons. She just wanted him to be Billy Graham or something.” In terms of her treatment of Amos, she recalls how “she’d pound into me that only evil women give away their virginity before marriage. If you even thought about doing that, you were out of the Kingdom of God.” Amos, for her part, was inclined to do more than just think about it, and was less than impressed by her grandmother’s suggestion that “a young woman should turn her body over to her husband, who then owns it.”

Amos, meanwhile, was developing a spirituality that was heavily influenced by her maternal grandparents, each of whom were deeply invested in their Cherokee heritage. (Each had a full-blooded grandparent.) From them she learned an animist spirituality—Amos recounts her grandfather teaching her to talk to trees and talk to her about shape-shifting, and credits him with helping her think of songs as coherent spirits that she has to nurture relationships with. Amos recounts talking with fairies into her adolescence before she began distancing herself from that aspect of herself in a largely unsuccessful bid at conventional popularity.

“Floating City” is not a song in which an adult Amos reclaims that spirituality. Instead it is the song of a soft atheist in the Richard Dawkins vein of “disbelieving very specifically in one god” looking to settle scores. Amos appeals to God to “come and take me away / I want to play / in your floating city” even as she decries His abandonment. Indeed, Amos is clearly unwilling to quite side with the unbelievers here, using the inclusive first person plural when she talks about how “TV turns off / any of us that say / that we’ve seen you,” creating a strange disjunct with her claims of abandonment. Instead she positions herself on the outskirts of the floating city, peppering God with questions: “is your city paved with gold? / Is there hunger? / Do your people grow old?”

As the song continues, its focus widens to a more general spiritual critique, wondering if it’s “weak to look for Saviors out in space” while musing that the Earth must be increasingly sick of humanity’s errors. It’s a stunningly broad swath of subject matter, and wildly more ambitious than Amos can handle at this point. But on an album whose concerns are generally as petty as “Fire on the Side” or “Heart Attack at 23” (which serves, bewilderingly, as the follow-up to this) reckless over-ambition is mostly a virtue. And while Amos isn’t up to the task of waging an impassioned argument with God just yet, the occasion still sees her offering a far more lively and nuanced lyric than the rest of the album. Her inquiring whether in God’s “governments have secrets that they’ve sold” is leagues ahead of most entries in the overcrowded genre of pop stars interrogating God. And her casual and entirely credulous invocation of Atlantis in the second verse as a point of comparison with the modern world is delightfully weird and unexpected. Even the title image, describing heaven as a “floating city” (and this after already questioning whether it’s a flawed creation), feels like an artist with a perspective and a vision in the way that other songs on the album simply don’t.

Musically, the song is largely indifferent.. At five minutes and nineteen seconds it’s the longest song on the album (assuming one treats the three songs of the “Etienne Trilogy” individually), which, given that second place is “Heart Attack at 23,” isn’t quite an endorsement of its importance, and features relatively little dynamism in its music. The verses are built on an arpeggiating synth line that moves between an Ebm and a Db, while the verses start on the Db and move to an Abm. The drums, bass, and guitar keep a relatively consistent pattern with a handful of guitar embellishments during the instrumental at the start of the third verse, but mostly the song just keeps on at this tone. The good part of this is that it keeps the song from becoming overbearing. The bad part is that it gets a bit sleepy, and can even be a bit of a slog.

Fittingly given the position it takes with regards to God, “Floating City” occupies something of a nearly position with regards to later acceptance. It doesn’t make any sort of appearance live until 2014, and only gets a trio of performances there, putting it one behind “On the Boundary” in total. But on the other hand, it was embraced enough to get a sheet music release alongside “Etienne” (and, hilariously, “Baltimore”) in the 1996 Bee Sides collection. These days, on the rereleased version of the album, it’s one of three songs that Apple Music marks as one of the most popular on the album, alongside “Fire on the Side” and “Cool on Your Island“—a straightforwardly correct choice on the part of the wisdom of crowds.

Fittingly given the position it takes with regards to God, “Floating City” occupies something of a nearly position with regards to later acceptance. It doesn’t make any sort of appearance live until 2014, and only gets a trio of performances there, putting it one behind “On the Boundary” in total. But on the other hand, it was embraced enough to get a sheet music release alongside “Etienne” (and, hilariously, “Baltimore”) in the 1996 Bee Sides collection. These days, on the rereleased version of the album, it’s one of three songs that Apple Music marks as one of the most popular on the album, alongside “Fire on the Side” and “Cool on Your Island“—a straightforwardly correct choice on the part of the wisdom of crowds.

Live and stripped down, “Floating City” becomes even more straightforward, largely to its detriment. The ways in which it foreshadowed Amos’s future strengths ironically become weaknesses, leaving the song looking like an undercooked Tori Amos song instead of a stirring of potential from back in her Y Kant Tori Read days. Taking up as much as seven minutes, it’s a flat and slightly over-earnest ballad. Its best outing came in 2015 during a televised performance for the Swiss Baloise Session festival, where she introduced the song in terms of how lucky she was to have had a failed first record that sent her career in the direction it ultimately went. Opening with a nearly minute long instrumental intro that recapitulates the old synth line into a simple one-handed figure on the piano, her other hand working the synthesizer, Amos perched between them, eyes closed in quiet reverie, swaying on her bench. Layering some light reverb on her vocals in the chorus, as she reaches the line “by my window at night / I see the light / to your floating city” (the light having become singular from the original so as to make the phrase more directly echo evangelical terminology), her eyes lift upwards towards her old rival , a joyful smile playing across her face as she restates the terms of their feud. She’s not played it since; it’s hard to imagine why she’d need to.

Recorded somewhere in 1987 or 1988 at any of half a dozen studios in the Los Angeles area. Played thrice on the 2014-15 tour.

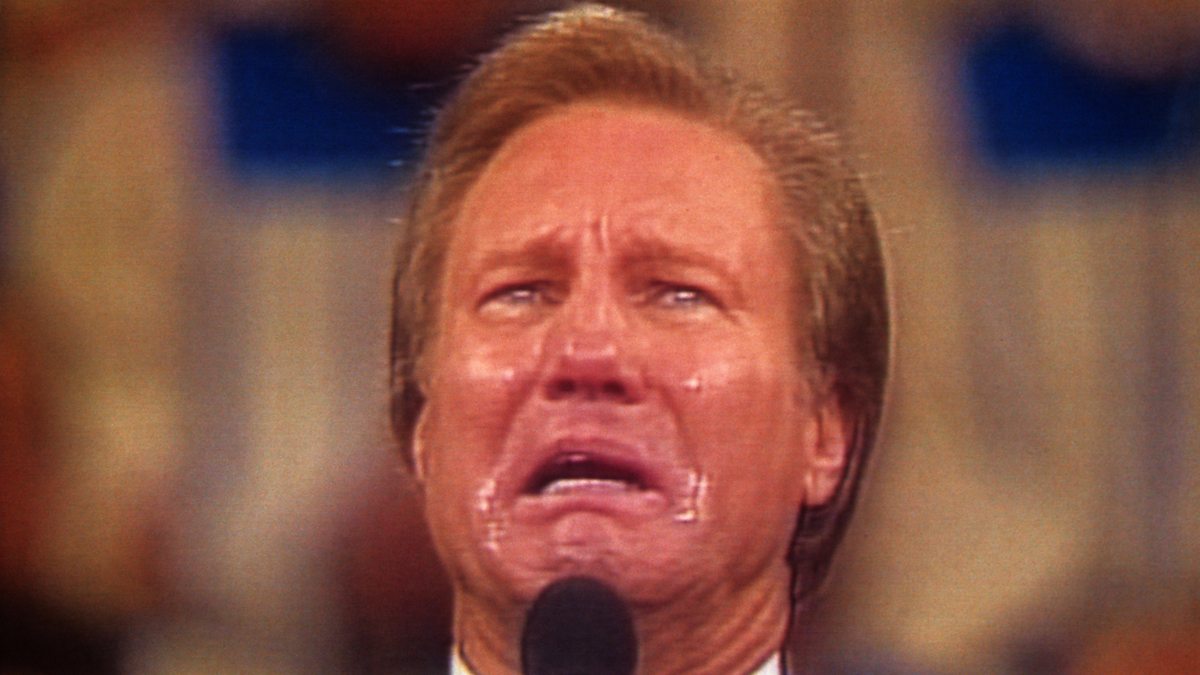

Top: Jimmy Swaggert apologizing, 1988; Amos at the 2015 Baloise session

Floating City (1988)

Floating City (1988)

September 23, 2019 @ 8:40 am

A good writer always is the king of the content. A good write assemble their mind thoughts into words on paper