Waiting For Somebody Else to Understand (Silent All These Years)

Silent All These Years (live, 1991)

Silent All These Years (live, 1991)

Silent All These Years (TV performance, 1991)

Silent All These Years (music video, 1992)

Silent All These Years (TV performance. 1992)

Silent All These Years (TV performance, 1994)

Silent All These Years (TV performance, 1996)

Silent All These Years (TV performance, 1997)

Silent All These Years (live, 1997)

Silent All These Years (TV performance, 1998)

Silent All These Years (TV performance, 2003)

Silent All These Years (live, 2005 official bootleg)

Silent All These Years (radio performance, 2007)

Silent All These Years (live, 2007, official bootleg, Tori set)

Silent All These Years (radio performance, 2014)

Silent All These Years (TV performance, 2017)

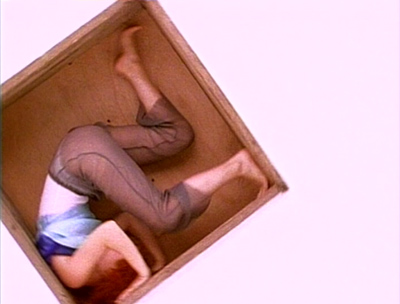

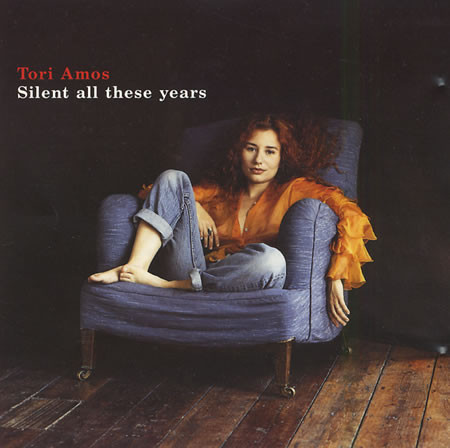

In many ways, it is Amos’s signature song. It’s not her biggest hit but it’s the song one turns to in order to encapsulate her. It was the one picked for rerelease as a single to benefit RAINN in 1997, the one she’s played on scads of TV and radio performances across her career, and the one picked as the leading single for the album in both the US and UK (even if the first UK release was titled “Me and a Gun,” that was track three on a four-track single that led with “Silence All These Years”). Even within the context of Little Earthquakes it’s clearly given an iconic status, its video being the one whose central visual image of Amos straining against the sides of a wooden crate got adapted as the album cover.

Like any attempt to summarize an artist in a single song, it leaves lots out—indeed in many ways “Silent All These Years” is a highly atypical Tori Amos song, though that’s in many ways the way of singular songs, which are by their nature singular. But the song is in the end iconic and deeply relatable. Its chorus—“sometimes I hear my voice / and it’s been here / silent all these years”—captures an experience of discovering one’s previously unknown strength and vision that is near universal among women, and frankly not even that uncommon among men.

What is easy to miss in the face of this weight and impact is how utterly weird all of this is. Yes, the title drop is a big relatable moment that effectively captures an important experience in a way that has enormous cultural significance in the larger context of women in pop music. But let’s look to the other end of the chorus, where Amos calmly asks “what if I’m a mermaid / in these jeans of his with her name still on it?” Sure, the image of wearing your boyfriend’s old and mostly discarded jeans that have an ex’s name stitched on them is at least emotionally accessible, if not exactly a universal experience, but… a mermaid?

I could go on—certainly the first verse gives several opportunities for extreme puzzlement. But my point isn’t to have a good laugh about how wacky Tori Amos is. For one thing, I don’t actually think that’s a fair description of her. Certainly it’s not fair to suggest any purposelessness in her strangeness—the mermaid line may be odd, for instance, but it’s a perfectly coherent Hans Christian Andersen reference in the larger context of the song. For another, even if it were, it wouldn’t be interesting. Yes, it’s strange that a song as idiosyncratic as “Silent All These Years” was as vastly influential as it was. But if your reaction to that is to chuckle at the strangeness you’re pretty definitely missing the point.

What is the point, then? Well, for one thing the point is that we probably need a smarter way to talk about relatability than the banal assumption that it hinges on universal applicability. And “Silent All These Years” in many ways exemplifies the flaws in that assumption. The song wouldn’t work if Amos’s newly liberated voice were generic. The song requires idiosyncrasy—that the voice being uncovered be striking, even uncanny and weird. It can’t be so alien as to be unrelatable, but that accessibility has to come in flashes, and be “I’ve felt like that” as opposed to “that describes me.”

As always, Amos is putting a lot of craft into making strangeness work. It’s notable that, while the song is odd throughout, it’s disproportionately odd in the first verse, which offers a chain of non-sequiturs including the assertion that the antichrist is yelling at her from her kitchen, that her salvation lies in the garbage truck, and, perhaps most strikingly, that these things are both routine enough to merit the word “again.” From there we go to the musing on being a mermaid, and finally to the title drop and its big moment of relatability. This does not mark the first time the song offers the listener a toehold in among the strangeness—the “yes I know what you think of me / you never shut up” couplet is perfectly relatable too, but it still comes after the antichrist and the garbage truck. The song is front-loading its weirdness, making sure to communicate “I’m really odd” very clearly before offering the listener space amidst the mermaids and antichrists.

As always, Amos is putting a lot of craft into making strangeness work. It’s notable that, while the song is odd throughout, it’s disproportionately odd in the first verse, which offers a chain of non-sequiturs including the assertion that the antichrist is yelling at her from her kitchen, that her salvation lies in the garbage truck, and, perhaps most strikingly, that these things are both routine enough to merit the word “again.” From there we go to the musing on being a mermaid, and finally to the title drop and its big moment of relatability. This does not mark the first time the song offers the listener a toehold in among the strangeness—the “yes I know what you think of me / you never shut up” couplet is perfectly relatable too, but it still comes after the antichrist and the garbage truck. The song is front-loading its weirdness, making sure to communicate “I’m really odd” very clearly before offering the listener space amidst the mermaids and antichrists.

It’s ironic, then, that a song as iconically Amos’s as “Silent All These Years” began life as a composition for Al Stewart. It’s not entirely clear how this worked. On the one hand, Amos notes that she’d composed “the melody, not the lyrics” for Stewart. On the other hand, she tells the story of her boyfriend, Eric Rosse, listening to the song and telling her “you’re out of your mind, thats your life story,” which suggests there must have been some words. In the end, it’s hard enough to believe that Amos ever proposed Al Stewart sing the line “boy you best pray that I bleed real soon” that we should probably assume the bulk of the lyric wasn’t written for Stewart.

The fact that it was written with Stewart in mind suggests the song, or at least part of it, emerged from the early end of Little Earthquakes—indeed I’m probably treating it slightly later than is accurate. This is a song that belongs with “Take to the Sky,” with Amos crafting herself mission statements and manifestos, declaring the terms on which she means to do business. But it’s also clear that the song arrived slowly, starting with what Amos describes as “the bumble bee piano tinkle” (“You know that bumblebee song? I decided that that song tortured me so I’m going to pay it back”) and building outwards.

It’s notable that this meticulous constructon was, as befits the song, entirely focused on its own internal aesthetic. Amos has said that the song “has a certain story line going on musically that’s really the antithesis of what’s going on verbally. It’s counterpoint, pure and simple. But instead of French horns and cellos or something, it’s words and music. And I find it very exciting when an acoustic instrument has its knife out.” And this tracks. But what’s notable is how little work went into contextualizing “Silent All These Years” with anything else going on at the time. Amos notes that the musical influences of the time were in the midst of a transition from “a time with a lot of emphasis on Depeche Mode and into a time of Nirvana.” And while it’s safe to say that Amos is well outside the mould of either (although eventually she’ll make an overt response on both, to varying degrees of success), it’s worth stressing how unlike anything else in pop music “Silent All These Years” was.

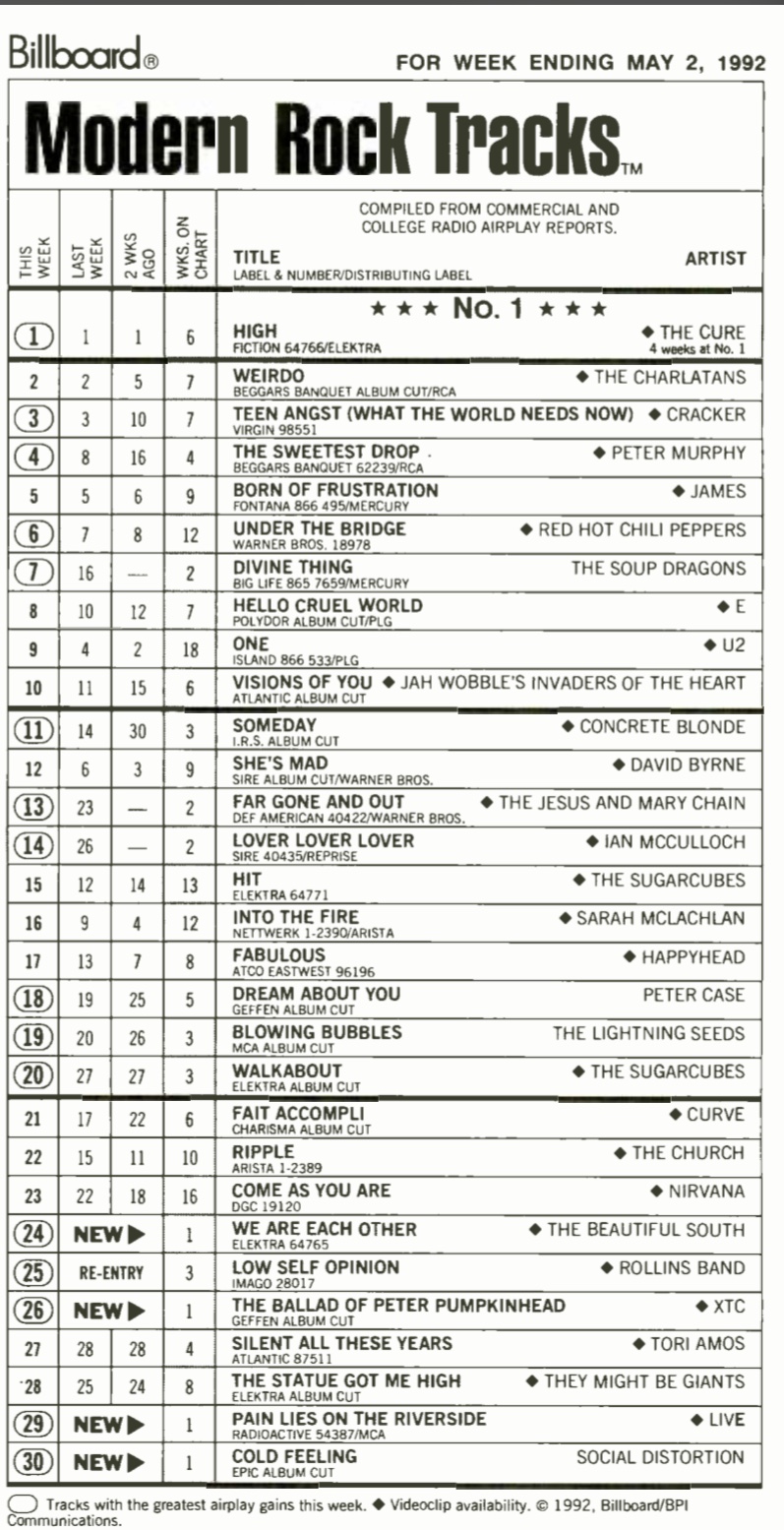

Let’s start with the Billboard Modern Rock charts on which the song hovered in the lower reaches for a few weeks, peaking at 27th on a 30-item chart in early May, 1992. To put it mildly, “Silent All These Years” sounded like absolutely nothing anything else on that chart. For one thing, it’s the only song in that chart with no drums; its sole percussion is a finger cymbal on the three-beat of the chorus that does not exactly dominate the mix. More obviously, it’s the only one with any prominent piano.

But the observation that Amos’s musical style was idiosyncratic for the period is hardly novel. Let’s contextualize her as best we can. The Modern Rock chart in May was as Amos described it—the last gasp of 80s new wave jostling with the early emergence of 90s alternative. As you’d expect from a changing of the guard it’s the latter tendency that offers the most iconic songs, with Red Hot Chili Peppers “Under the Bridge” and Nirvana’s “Come As You Are” both making appearances. The former, meanwhile, is a bunch of venerable acts offering things other than their biggest hits—The Cure with the song on Wish that isn’t “Friday I’m in Love,” along with second or third tier songs from David Byrne, XTC, and Peter Murphy. Straddling the chronological gap are U2 with “One,” but it’s notable that the divide is just as easily described geographically, with the 80s side comprising British bands while the 90s are largely American. (Amos was American, but Atlantic sent her to the UK to break out there first, so she fails to classify easily here in more ways than one.)

But the observation that Amos’s musical style was idiosyncratic for the period is hardly novel. Let’s contextualize her as best we can. The Modern Rock chart in May was as Amos described it—the last gasp of 80s new wave jostling with the early emergence of 90s alternative. As you’d expect from a changing of the guard it’s the latter tendency that offers the most iconic songs, with Red Hot Chili Peppers “Under the Bridge” and Nirvana’s “Come As You Are” both making appearances. The former, meanwhile, is a bunch of venerable acts offering things other than their biggest hits—The Cure with the song on Wish that isn’t “Friday I’m in Love,” along with second or third tier songs from David Byrne, XTC, and Peter Murphy. Straddling the chronological gap are U2 with “One,” but it’s notable that the divide is just as easily described geographically, with the 80s side comprising British bands while the 90s are largely American. (Amos was American, but Atlantic sent her to the UK to break out there first, so she fails to classify easily here in more ways than one.)

Cynical as it may be, the most direct points of comparison for Amos are probably the acts with female vocalists. But even here Amos is wildly singular. Curve’s “Fait Accompli” has the dark swagger that Y Kant Tori Read failed so abjectly at, and trying to sell it as a harder cousin of “Little Earthquakes” is probably a fun game over drinks. Concrete Blonde’s “Someday” would work if Amos were displaying any southern influences yet. And Jah Wobble’s Invaders of the Heart’s “Visions of You” features a guest vocal from Sinead O’Connor, who’s certainly worth comparing to Amos so as to answer pressing questions like “why do ripping up a photo of the Pope and breast feeding a pig have such wildly different impacts on your career,” but that doesn’t actually make the songs similar.

The consensus pick for the song most comparable to “Silent All These Years” would probably be Sarah McLachlan’s “Into the Fire.” This leans hard into the cynicism of treating women as a genre, but that doesn’t change the basic similarities between Amos’s song and a lyric that opens “Mother teach me to walk again.” Women aren’t a genre, but there are common concerns, and the assertion of one’s agency is certainly one. The savvier pick might be either of the two Sugarcubes songs to chart, both of which feature Björk on vocals instead of Einar Örn Benediktsson. Certainly the Sugarcubes share Amos’s willingness to just plain be odd, and Björk offers a similar sense of visionary singularity to Amos, but again, the differences massively outstrip the similarities.

(In practice the song on the Modern Rock charts that week that had the most fans who were ride or die for both it and “Silent All These Years” was probably They Might Be Giants’ “The Statue Got Me High.” You might reasonably expect me to have some unique insight into why this is; I do not.)

(OK, fine—it’s probably notable that John Linnel, Björk, and Tori Amos are, along with David Byrne, the four songwriters on that chart most willing to just be flat-out weird. Sometimes the feeling of being different is more important than the precise mechanics, lyrically or musically, of exactly how you’re different. It might also be worth noting that both They Might Be Giants and Tori Amos had their first Internet mentions on rec.arts.gaffa, a discussion group for noted musical weirdo Kate Bush.)

This is unusual for pop music, which tends to move in trackable waves. The larger narrative of British post-punk giving way to grunge and alternative plays out on a large scale, with dozens of individual artists (and fans) swept along in its wake. Nirvana may have been a breath of fresh air as the musical styles of the 80s began to run out of steam, but they didn’t come from nowhere—they were the first big success of an existing musical scene with clear stylistic and geographical roots. For all their impact, they’re ultimately replaceable—take them out and Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains would all still have existed and done much the same cultural work.

This is simply not true for Tori Amos. She can still be discussed in terms of influences and inspirations—eventually we’re going to have to unpack that Kate Bush thing in a little more detail. But she is not the leading edge of a shift in musical style (even as the next couple years of pop music are going to prove enormously generous to female singer-songwriters, none of them sound like her). She is her own thing, and had she given up after Y Kant Tori Read instead of regrouping and reinventing herself there would have been no replacement for her.

In this regard it’s fitting that “Silent All These Years” became her signature song for the simple reason that it foregrounds the right thing. More than any other artist in the aforementioned wave of female singer-songwriters in the 90s, Amos is defined by the singularity of her voice—by the fact that the universe forged by her music does not sound like anyone else’s, nor is it concerned about the same things. Where most pop stars exist in a strange and complicated balance of being relatable and being an aspirational figure, Tori Amos is not quite either of these things. For all the flashes of relatability and familiar experience in her work, she is ultimately too strange to project one’s self onto, either as a “she really understands how I feel” figure or as a role model. Instead she sits out on a frontier of her own devising, not so much exploring possibilities as defining and discovering them with her every move.

Recorded in Los Angeles at Capitol Records in 1990, produced by Davitt Sigerson. Video directed by Cindy Palmano. Orchestral version recorded in at Martian Engineering in 2011-12, produced by Tori Amos. Played throughout Amos’s career.

December 10, 2019 @ 9:18 am

https://apkmist.com/lucky-patcher-apk/

For all the flashes of relatability and familiar experience in her work, she is ultimately too strange to project one’s self onto, either as a “she really understands how I feel” figure or as a role model.

July 27, 2020 @ 11:11 am

No need to rack your brains, thinking on how to do academic papers! Use Qweetly.com . There are a lot of templates of assignments on all subjects.

May 23, 2023 @ 10:05 pm

I think you totally missed the point of the song.

May 23, 2023 @ 10:16 pm

What, exactly, do you think I’m wrong about?