|

| If this were Doctor Who, we’d call it the pizza-faced Oberyn. |

State of Play

The choir goes off. The board is laid out thusly:

Lions of King’s Landing: Tyrion Lannister, Jaime Lannister, Cersei Lannister, 2Tywin Lannister

Dragons of Meereen: Daenerys Targaryen

Direwolves of the Wall: Jon Snow

The Mockingbird, Petyr Baelish

Kraken of Moat Cailin: Theon Greyjoy

Archers of the Wall: Samwell Tarly

The Direwolves, Sansa Stark, Arya Stark

Bows of the Wall: Ygritte

Paws of the Wall: Tormund Giantsbane

Flowers of the Wall: Gilly

Flayed Men of Moat Cailin: Ramsay Snow

Spiders of King’s Landing: Varys

The Dogs, Sandor Clegane

With the Bear of Meereen, Jorah Mormont

Winterfell is abandoned and in ruins, Braavos is empty.

The episode is in eight parts. The first runs six minutes and is in two sections; it is set in and around the Wall. The first section is four minutes long; the opening image is of a thatched hut. The second section is two minutes long; the transition is by dialogue, from Gilly to Samwell talking about how she’s probably dead.

The second part runs five minutes and is set in Meereen. The transition is by hard cut, from Jon Snow drinking morosely to an underwater shot of Grey Worm, and indirectly by family, with Daenerys showing up shortly.

The third runs five minutes and is set in Moat Cailin. The transition is by hard cut, from Grey Worm to an establishing shot of the Bolton camp.

The fourth runs eight minutes and is set in the Eyrie. The transition is by hard cut, from Theon to a slow pan up Littlefinger’s coat.

The fifth runs six minutes and is set in Meereen. The transition is by hard cut, from Littlefinger and company in the Eyrie to the masters being (rather belatedly) removed from their crosses.

The sixth runs three minutes and is set at Moat Cailin. The transition is by image, from a wide shot of Meereen to one of the Bolton forces.

The seventh runs five minutes and is in three sections; it is set in the Eyrie. The first section is one minute long; the transition is by hard cut, from a wide shot of the Boltons riding to Sansa in her chambers. The second section is two minutes long; the transition is by family, from Sansa to Arya Stark. The third section is one minute long; the transition is by dialogue, from Arya laughing at Lyssa Arryn’s death to Robyn and Littlefinger talking about her.

The last part runs eleven minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by family, from Sansa to Tyrion. The final image is of Tyrion having landed on a snake and been sentenced to death.

Analysis

As with “The Prince of Winterfell” two years prior, the decision to make the ninth episode a single location battle benefits the eighth episode, into which a number of climaxes are shifted. But with the increased number of plots in progress compared to two years ago, this means that two-and-a-half plots resolve outright in this episode, their handling comprising the majority of the episode.…

Continue Reading

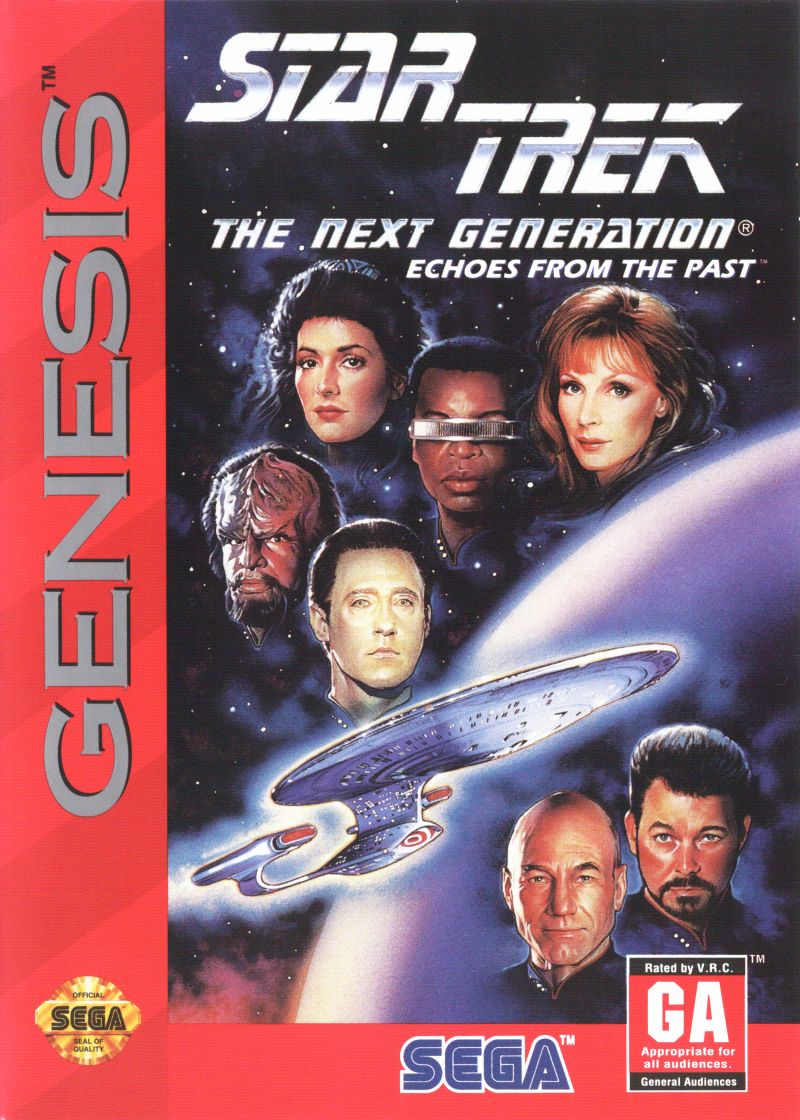

This is far and away among the weirder story arcs in the DC Star Trek: The Next Generation series. And given this is a comic book line that had the Enterprise literally meet Santa Claus in 1987, that goes a way towards saying something. And yet Divided Light is *just* audacious and weird enough to work: Michael Jan Friedman’s signature deft hand at writing the crew and his knack for having his stories’ main themes and motifs reoccur on multiple levels makes this one memorable for all the right reasons instead of all the wrong ones. Perhaps most importantly for our purposes, it marks the beginning of a critical and formative time when the spin-off media, particularly the comic books, steered the course of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

This is far and away among the weirder story arcs in the DC Star Trek: The Next Generation series. And given this is a comic book line that had the Enterprise literally meet Santa Claus in 1987, that goes a way towards saying something. And yet Divided Light is *just* audacious and weird enough to work: Michael Jan Friedman’s signature deft hand at writing the crew and his knack for having his stories’ main themes and motifs reoccur on multiple levels makes this one memorable for all the right reasons instead of all the wrong ones. Perhaps most importantly for our purposes, it marks the beginning of a critical and formative time when the spin-off media, particularly the comic books, steered the course of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

In

In

ilm, rather than a sixty-five year old piece of film noir history. Shana was still out of town (but she’ll be back next week), so I was joined by friend of the show Jessica from The Web of Queer (which is a show more people should know about, so go click that link) to discuss the

ilm, rather than a sixty-five year old piece of film noir history. Shana was still out of town (but she’ll be back next week), so I was joined by friend of the show Jessica from The Web of Queer (which is a show more people should know about, so go click that link) to discuss the  I was supposed to write an essay for you guys this week, hypothetically on de-normalizing the nuclear family, but I sort of fell into the RNC k-hole for a couple of days and found myself much less productive while staring into the gaping maw of that Nuremberg Rally/reality show blend as put on by some third-rate high school AV Club. That’s the official version I’m presenting to the public, at least.

I was supposed to write an essay for you guys this week, hypothetically on de-normalizing the nuclear family, but I sort of fell into the RNC k-hole for a couple of days and found myself much less productive while staring into the gaping maw of that Nuremberg Rally/reality show blend as put on by some third-rate high school AV Club. That’s the official version I’m presenting to the public, at least.  I’m sorry, but I have nothing substantive for you this week. I have several things half-finished, but that’s obviously not good enough.

I’m sorry, but I have nothing substantive for you this week. I have several things half-finished, but that’s obviously not good enough.

We now begin what I consider to be the second act of LOST’s first season. The basic tenor of the show has now been laid out – our principal characters have been introduced in some detail, as has the mysteriousness of the Island, and the general tenor of the show’s approach to episodic serialization has been established. Overall, it’s been a story of how these survivors of a plane crash have adapted to living on an island in the South Pacific, touching on issues of social organization through intense characterization. Now the show begins to shift focus, adding new dimensions: not only will some of the mysteries introduced early on be revealed, but it starts exploring the implication of the fact that our survivors are not alone.

We now begin what I consider to be the second act of LOST’s first season. The basic tenor of the show has now been laid out – our principal characters have been introduced in some detail, as has the mysteriousness of the Island, and the general tenor of the show’s approach to episodic serialization has been established. Overall, it’s been a story of how these survivors of a plane crash have adapted to living on an island in the South Pacific, touching on issues of social organization through intense characterization. Now the show begins to shift focus, adding new dimensions: not only will some of the mysteries introduced early on be revealed, but it starts exploring the implication of the fact that our survivors are not alone.