The Mushrooms Of Youth (Super Mario All-Stars)

Our past, reflected back, is a strange sight, especially the first time we glimpse it. Nostalgia made its Nintendo debut in 1990 with Mega Man 3, a point I have discussed elsewhere. But the first time Nintendo itself embraced it came in 1993, when they released Super Mario All-Stars, a compilation of the three NES Super Mario Bros. games alongside, depending on your country, either Super Mario USA or Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels, all given a 16-bit graphics remaster.

Our past, reflected back, is a strange sight, especially the first time we glimpse it. Nostalgia made its Nintendo debut in 1990 with Mega Man 3, a point I have discussed elsewhere. But the first time Nintendo itself embraced it came in 1993, when they released Super Mario All-Stars, a compilation of the three NES Super Mario Bros. games alongside, depending on your country, either Super Mario USA or Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels, all given a 16-bit graphics remaster.

This seems positively ordinary these days, when HD remixes, mobile rereleases, and emulator-based compilations of classic games are everywhere. Indeed, in the age of Super Mario Maker this feels in some ways like the most pointless thing imaginable. But in 1993 it was genuinely unusual in the console market, and this game has to be read and understood in that context. Perhaps more importantly, it needs to be understood in the context of the very upgrade cycle nostalgia cuts against, not least because their relationship is oppositional, not antagonistic. (That’s the trouble with Nemeses.)

Put another way, a large part of why Super Mario All-Stars exists is simply that the NES was finally giving up the ghost in 1993. When this dropped at the start of August there was essentially only a year to run in terms of NES games (the only exception being Wario’s Woods, which ambled out four months later), and only twenty-eight more releases for the system total; the SNES had more than that before Christmas. And Super Mario All-Stars has to be read as an attempt to manage that transition, symbolically marking the end of the old system. Part of this, in turn, is motivated simply by the fact that the Mario games were perennial sellers that Nintendo knew full well they could continue profiting off of after their system went the way of all things.

But more fascinating than the reasons for its existence is the object itself. It is, in hindsight, a strangely kitsch object. The redone graphics are distinctly lovely, but are somehow less satisfying than the original games in all three cases. The vagaries of personal history require that there be someone, somewhere for whom these are the true versions of the games, crackling with the crazed and giddy thrill of childhood discovery and totemic power, but no matter the degree of their ardor, even they recognize the perversity of this belief.

Playing them, there is something ineffably unsatisfying. The controls feel looser and sloppier somehow. It is possibly, even probably an illusion. And yet the feeling is inevitable somehow. The curated, museum-like approach of the games put them at a strange remove, so every death, even if it is entirely our own fault, feels as though the game has let us down.

Or perhaps like we have let it down, and grown too sophisticated for its pleasures. This is especially visible when playing Super Mario Bros. It’s obviously not that the game, legitimately one of the great all-time classics of the medium, has aged poorly.…

Is ‘Y’ a vowel or a consonant?

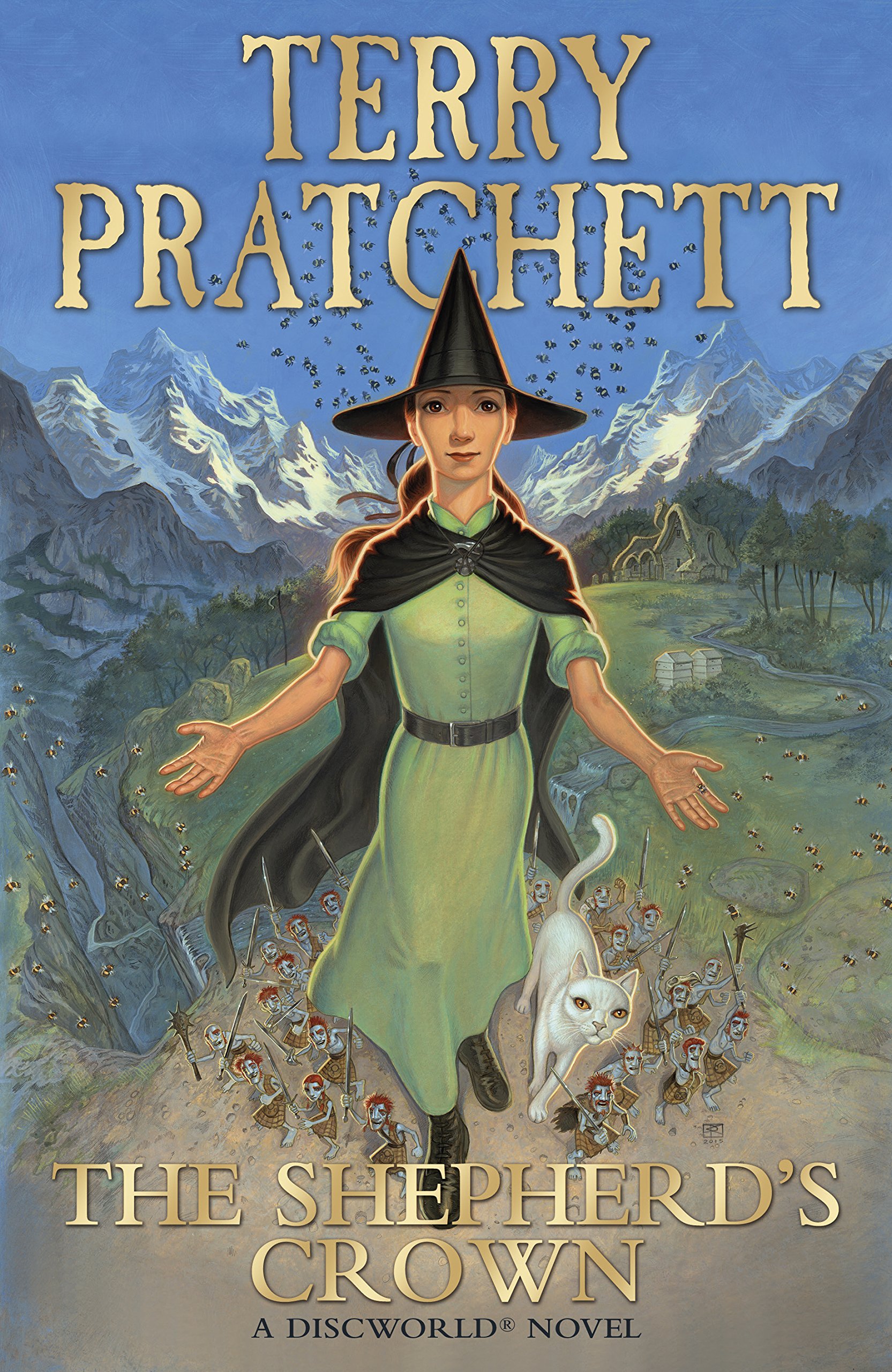

Is ‘Y’ a vowel or a consonant? The Shepherd’s Crown by Terry Pratchett

The Shepherd’s Crown by Terry Pratchett Oh good, they didn’t just completely forget how to make

Oh good, they didn’t just completely forget how to make  Ah, Best Novelette. The form that only the Hugos actually recognize, occupying the space between short story and short novel. Long story, as it were. Or, in technical terms, anything between 7,500 and 17,500 words long, because obviously people know the word length of things they read.

Ah, Best Novelette. The form that only the Hugos actually recognize, occupying the space between short story and short novel. Long story, as it were. Or, in technical terms, anything between 7,500 and 17,500 words long, because obviously people know the word length of things they read. Following Jack’s

Following Jack’s

This week I’m joined by the wonderful Anna Wiggins, known to Eruditorum Press readers for her guest posts in the Super Nintendo Project and TARDIS Eruditorum, and known to Eruditorum Press writers as the person who makes the site actually work. Anyway, we talk Before the Flood, Toby Whithouse, disability representation, Whithouse’s frequent blind spots with regards to transgender and feminist issues, and many more reasons why we just don’t like Toby Whithouse all that much. Honest, it’s not a site editorial position or anything.

This week I’m joined by the wonderful Anna Wiggins, known to Eruditorum Press readers for her guest posts in the Super Nintendo Project and TARDIS Eruditorum, and known to Eruditorum Press writers as the person who makes the site actually work. Anyway, we talk Before the Flood, Toby Whithouse, disability representation, Whithouse’s frequent blind spots with regards to transgender and feminist issues, and many more reasons why we just don’t like Toby Whithouse all that much. Honest, it’s not a site editorial position or anything.