And do you know what she said? Her most famous quotation? (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part 13: Before Watchmen: The Comedian)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore and Grant Morrison’s differences of opinions are numerous, but one of the most fundamental differences comes in their relationship to the atomic bomb. Both were profoundly concerned with nuclear warfare, but for Morrison it was a childhood fear he found respite from in superheroes, whereas for Moore it was an adult concern he worked through using superheroes as a metaphor.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore and Grant Morrison’s differences of opinions are numerous, but one of the most fundamental differences comes in their relationship to the atomic bomb. Both were profoundly concerned with nuclear warfare, but for Morrison it was a childhood fear he found respite from in superheroes, whereas for Moore it was an adult concern he worked through using superheroes as a metaphor.

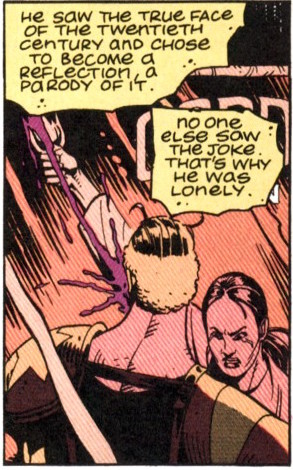

In many ways, this is the heart of the disagreement between Pax Americana and Watchmen. Morrison sees superheroes as creatures of immense possibility whose value is as aspirational figures. For him it is the interminability of superhero narratives that is most interesting – the fact that characters get reinvented over and over again, with new ideas and new takes, and that the stories never have to come to an end. Whereas to Moore, at least in Watchmen, what is interesting are the limitations of superheroes – of what they are incapable of doing and representing. The superheroes of Watchmen are known archetypes that the audience has seen a hundred times before, only taken to logical endpoints. The point isn’t the possibility of the characters, it’s the impotence of them. Put another way, Morrison cares what superheroes let us be, while Moore cares what they let us see.

This division, or at least the underlying division over what the purpose of art is, is one that will persist, in some form or another, throughout the War. But ironically, when it comes to the actual disagreement over the possibility of superheroes as an optimistic genre, it is Morrison’s view that ultimately won the day. Part of Moore’s ultimate revulsion at Watchmen was precisely the way in which, as he put it, it became “a kind of hair shirt that the super-hero had to wear forever after that… they’ve all got to be miserable and doomed. And if they’ve got to be psychopathic as well, then so much the better.” Indeed, Moore was adamant that “imaginative fiction,” and specifically superhero fiction, “is something which is perfectly fine for adults,” a point he attempted to demonstrate in much of his superhero work following his departure from DC.

Arguably, then, this forms one of the few major chinks in Moore’s usually resilient armor of eternity – a point on which Moore can decisively and unambiguously be said to have changed. And yet it is easy to overstate this. Moore’s revulsion towards Watchmen is genuine, and yet it is not really a revulsion at the work itself. Rather, it is a revulsion at the world that Moore used Watchmen to look at – one that he found monstrous and twisted, and wrongly assumed that the rest of the world would see it that way as well. This is not just a matter of the fans who seized onto Rorschach in ways Moore found disturbing, but rather the entire way in which the nightmarish world he constructed, in which superheroes were the embodiment of humanity’s most self-destructive impulses tragically deluding themselves into believing that they were the world’s Watchmen and not its doom, was treated as something desirable.…

Arguably, then, this forms one of the few major chinks in Moore’s usually resilient armor of eternity – a point on which Moore can decisively and unambiguously be said to have changed. And yet it is easy to overstate this. Moore’s revulsion towards Watchmen is genuine, and yet it is not really a revulsion at the work itself. Rather, it is a revulsion at the world that Moore used Watchmen to look at – one that he found monstrous and twisted, and wrongly assumed that the rest of the world would see it that way as well. This is not just a matter of the fans who seized onto Rorschach in ways Moore found disturbing, but rather the entire way in which the nightmarish world he constructed, in which superheroes were the embodiment of humanity’s most self-destructive impulses tragically deluding themselves into believing that they were the world’s Watchmen and not its doom, was treated as something desirable.…

This week I’m joined by James Murphy of Pex Lives to discuss Under the Lake and, in typical Eruditorum Press style, a myriad of other topics, some of which actually have an obvious relationship to Under the Lake. Perversely, we manage to go on half an hour longer than Jane and I did about an actually good story. I have no explanation.

This week I’m joined by James Murphy of Pex Lives to discuss Under the Lake and, in typical Eruditorum Press style, a myriad of other topics, some of which actually have an obvious relationship to Under the Lake. Perversely, we manage to go on half an hour longer than Jane and I did about an actually good story. I have no explanation.  Bit of an unplanned diversion for the Tricky Dicky series, this. Normal service to be resumed soon. (This series was always intended as a free-associating ramble.) We’re going to Shakespeare, albeit not in the way originally planned, so Spoiler Warning… um, for a play first performed about 423 years ago. Oh, and Trigger Warning, for discussion of recent violent acts, and some hardcore misogyny.

Bit of an unplanned diversion for the Tricky Dicky series, this. Normal service to be resumed soon. (This series was always intended as a free-associating ramble.) We’re going to Shakespeare, albeit not in the way originally planned, so Spoiler Warning… um, for a play first performed about 423 years ago. Oh, and Trigger Warning, for discussion of recent violent acts, and some hardcore misogyny. From worst to best of what I paid money for, sometimes reluctantly.

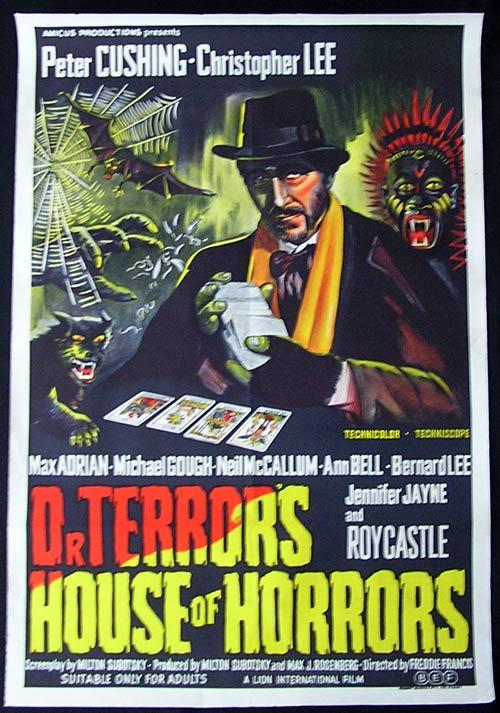

From worst to best of what I paid money for, sometimes reluctantly. Along with Pex Lives itself and the Shabcast, one of the podcasts Eruditorum Press picked up when we took Kevin and James onboard was Holly Boson and James Murphy’s City of the Deadpodcast, which is looking at all of the releases from Amicus Films in turn. Readers of this site probably know Amicus best for the two Peter Cushing Dalek films, but on the whole they’re better known for a series of horror anthology films that James described to me as a sort of cut-rate Hammer Horror. Today we’ve got a look at Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, a five-part anthology film featuring Peter Cushing as Dr. Terror instead of as Dr. Who, telling the awful fates of people on a train.

Along with Pex Lives itself and the Shabcast, one of the podcasts Eruditorum Press picked up when we took Kevin and James onboard was Holly Boson and James Murphy’s City of the Deadpodcast, which is looking at all of the releases from Amicus Films in turn. Readers of this site probably know Amicus best for the two Peter Cushing Dalek films, but on the whole they’re better known for a series of horror anthology films that James described to me as a sort of cut-rate Hammer Horror. Today we’ve got a look at Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, a five-part anthology film featuring Peter Cushing as Dr. Terror instead of as Dr. Who, telling the awful fates of people on a train.

August 7th, 2015 will presumably not join January 24th, 1984 and October 23, 2001 on the list of celebrated Apple anniversaries. This will, I suspect, be a mistake. The release of Compton (all together now, “Dr. Dre’s first new album in sixteen years”) is every bit as significant a cultural moment as the Macintosh and the iPod, even if its status as a pop moment is likely to obscure its status as a moment in the history of tech culture, and, more broadly, the way it positions Dre as the king of both Compton and Cupertino, for good and for ill.

August 7th, 2015 will presumably not join January 24th, 1984 and October 23, 2001 on the list of celebrated Apple anniversaries. This will, I suspect, be a mistake. The release of Compton (all together now, “Dr. Dre’s first new album in sixteen years”) is every bit as significant a cultural moment as the Macintosh and the iPod, even if its status as a pop moment is likely to obscure its status as a moment in the history of tech culture, and, more broadly, the way it positions Dre as the king of both Compton and Cupertino, for good and for ill. “The Chair Agenda” refers to the symbolic use of a Chair to indicate a process of Ascension. But this rather begs the question of what we mean by “ascension” and what, if anything, chairs have to do with it. I mean, it’s not like there’s anything about chairs in of themselves that would lead us to associate them with Ascension, is there?

“The Chair Agenda” refers to the symbolic use of a Chair to indicate a process of Ascension. But this rather begs the question of what we mean by “ascension” and what, if anything, chairs have to do with it. I mean, it’s not like there’s anything about chairs in of themselves that would lead us to associate them with Ascension, is there? We start with the Library, because it’s in the Library that Doctor Who first starts to make use of this symbolism relatively unambiguously. In the first episode, Silence in the Library, we get the first death of the story, that of Miss Evangelista (oooh, what a name!) She wanders into a reading room, where several chairs take the center stage, and one in particular looks almost like a throne, with upholstery in TARDIS blue. The camera pans behind the chair, behind some books… and then a scream. Our heroes come racing into the room, and discover a skeleton sitting in the high-backed chair.

We start with the Library, because it’s in the Library that Doctor Who first starts to make use of this symbolism relatively unambiguously. In the first episode, Silence in the Library, we get the first death of the story, that of Miss Evangelista (oooh, what a name!) She wanders into a reading room, where several chairs take the center stage, and one in particular looks almost like a throne, with upholstery in TARDIS blue. The camera pans behind the chair, behind some books… and then a scream. Our heroes come racing into the room, and discover a skeleton sitting in the high-backed chair. A little while ago, I said that I would write an essay of at least 1000 words, on any topic, for the first person to ask for one after I passed 500 followers on Twitter. I reached that milestone (hey, to me it’s a milestone) and immediately two people asked me simultaneously. One of them asked me to write about Kate Bush. So here goes.

A little while ago, I said that I would write an essay of at least 1000 words, on any topic, for the first person to ask for one after I passed 500 followers on Twitter. I reached that milestone (hey, to me it’s a milestone) and immediately two people asked me simultaneously. One of them asked me to write about Kate Bush. So here goes.