The Sea is the Sky (Flying Dutchman)

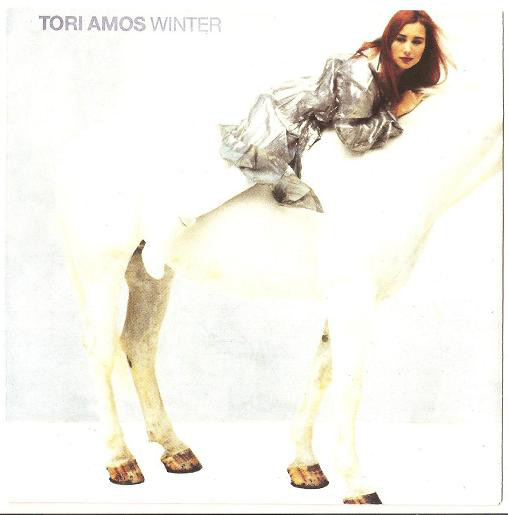

Some time early in Amos’s time in LA, while she was still playing the airport Holiday Inn to pay her rent, a friend of hers helped her move, and asked her kinda sorta boyfriend Rantz Hoseley to help. Hoseley was attending art school in the city, and the two hit it off immediately (Hoseley cameos in the video for “The Big Picture”). A few years later, in the wake of Y Kant Tori Read, Amos called her friend to chat. Hoseley, an artist who wanted to make it in the comics industry, had recently left Los Angeles after a number of setbacks that included being told by Marvel editor Tom DeFalco that he should give up and become a plumber and what he describes s “some very scary near-fatal experiences,” and was living with his parents in Washington, but the two remained close. Amos was starting to bounce back from her own setback and in the early stages of Little Earthquakes, and asked her friend how he’d describe himself. Hoseley’s response, delivered from the depths of his depressive spiral, was to say, “Tori, I’m the Flying Dutchman.” And so Amos began to write Hoseley a song.

By legend, the Flying Dutchman is a ghost ship doomed to sail the oceans forever. The stated origins of the curse are numerous. In some tellings, the ship was cursed after it committed some horrific crime; in others, its captain made an ill-advised invocation of the Devil. In any case, the ship is now cursed to never find a safe port. To sight it is to see disaster, not least as the ship exists perpetually within a patch of foul weather. (In practice, supposed sightings were most likely Fata Morgana mirages.)

The song is a soaring and expansive piece, making liberal use of (sampled) strings and clocking in at six and a half minutes, with multiple different verse structures that get employed over the course of it. (One reporter, rather fatuously, suggested the song has “a kind of movement-like structure,” to which Amos, rather more accurately, replied that “it’s not the structure of your typical pop song.”) Lyrically, it’s a rousing statement of belief, first in Hoseley, who she sympathetically portrays as being constantly badgered about what he’ll do with his life, and in the second verse describing a woman who is chronically misunderstood by the “straight suits.” This is possibly Amos portraying herself after the failure of Y Kant Tori Read. Picking up on Hoseley’s identification with the famous ghost ship, Amos spends the chorus hailing the missing ship, imagining it not as a bunch of lost souls desperate to get home, but as some sort of intrepid explorer of far-out conceptual realms. As she tells her characters, “they can’t see / what you’re born to be.”

Understandably given its use of canned strings, Amos picked the song to rework on Gold Dust, where it’s one of the few songs not to feel like a pale echo of its original.…

Flying Dutchman (1992)

Flying Dutchman (1992)

The only thing missing is the actual tense relationship between the Amoses. In fact Ed Amos is consistently supportive of his daughter, and has been throughout her life, from chaperoning her as she played Georgetown gay bars in her teens to any number of comments to the press in which he speaks warmly of his daughter’s career. This is not, to be clear, because he’s a radically progressive Christian. By all appearances he’s solidly moderate—Amos has spoken about her father’s support for the civil rights movement, but also made wry comments about how he’s evolved to seeing gay people as individuals instead of as a homogenous mass of “the gays.” Instead there’s a sort of wry pragmatism to his assessment of his daughter—one rooted in a profound respect for her ability. The relationship is perhaps best summed up by a comment Amos attributes to him in several interviews to the effect of “what would you have written about if I had been a dentist?”

The only thing missing is the actual tense relationship between the Amoses. In fact Ed Amos is consistently supportive of his daughter, and has been throughout her life, from chaperoning her as she played Georgetown gay bars in her teens to any number of comments to the press in which he speaks warmly of his daughter’s career. This is not, to be clear, because he’s a radically progressive Christian. By all appearances he’s solidly moderate—Amos has spoken about her father’s support for the civil rights movement, but also made wry comments about how he’s evolved to seeing gay people as individuals instead of as a homogenous mass of “the gays.” Instead there’s a sort of wry pragmatism to his assessment of his daughter—one rooted in a profound respect for her ability. The relationship is perhaps best summed up by a comment Amos attributes to him in several interviews to the effect of “what would you have written about if I had been a dentist?” Happy Phantom (demo, 1990)

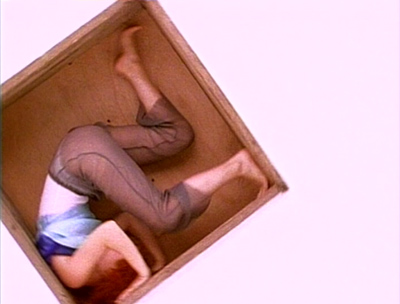

Happy Phantom (demo, 1990) Upside Down (live, 1991)

Upside Down (live, 1991) Silent All These Years (live, 1991)

Silent All These Years (live, 1991) Sweet Dreams (demo, 1990)

Sweet Dreams (demo, 1990) Mother (1992)

Mother (1992) Leather (live, 1991)

Leather (live, 1991)