It’s November 19th, 2016. Clean Bandit has debuted at number one with “Rockabye,” while Rae Sremmurd, Bruno Mars, James Arthur, and the Weeknd also chart. In news, the British Medical Journal calls for the legalization of drugs while Donald Trump agrees to pay $25m in settlements over Trump University.

It’s November 19th, 2016. Clean Bandit has debuted at number one with “Rockabye,” while Rae Sremmurd, Bruno Mars, James Arthur, and the Weeknd also chart. In news, the British Medical Journal calls for the legalization of drugs while Donald Trump agrees to pay $25m in settlements over Trump University.

On television, meanwhile, Class does its bottle episode. As with “Nightvisiting,” there is a sense of “really, already?” to this. The bottle episode is a classic contrivance. And while better shows than Class have gotten to them as soon as their third stories, they are generally a sign that something has gone oddly somewhere else in the season. In this case the culprit is fairly obvious: this is a Quill-free episode done on the cheap. Next week we have a Quill-only episode that’s blatantly where the money has gone.

If this sounds familiar, it’s presumably because you’ve watched Doctor Who and remember Russell T Davies tossing David Tennant into a cheap bottle episode he wrote in basically two days so that he could have Catherine Tate and Billie Piper do a costly greatest hits tour of his era the week after. Indeed, the basic setup, with its incorporeal monster and ratcheting internal tensions, owes a pretty obvious debt to Midnight. And the other obvious source for an episode in which people are trapped somewhere and being made to confess is, of course, Heaven Sent, which lacks the budget motivations of a proper bottle episode but is still working in the same general mode.

A peculiarity of bottle episodes is that, despite generally being born of desperation, they’re also historically pretty good. This is easy enough to explain: countless artists across media have discovered the creatively liberating power of constraints. And so it is not a surprise that when Class both takes on this structure and starts pilfering the show it’s a spinoff of instead of deciding that its main peers are American shows that mostly air on the CW, things improve above the baseline.

This has a satisfyingly propulsive structure over its forty-five minutes. A weird disaster traps everyone in a classroom with a glowing rock that both compels the revelation of unpleasant truths and advances the plot when it’s picked up. One by one the characters pick it up. Wacky hijinks ensue. This is strong enough that a variety of small contrivances like “making everybody angry is an arbitrary and slightly hackish escalator,” “the explanation of what’s happening here only narrowly makes sense,” and “there’s not actually a clear reason why nobody can pick up the rock more than once” don’t really interfere with proceedings to any meaningful extent. This works, and does so with a breezy confidence that borders on swagger; something that Class generally comes nowhere near mustering.

At the heart of its success, and something that has consistently been rescuing Patrick Ness from peril, is that he really is quite good at writing adolescence. Characters fuck up in fundamentally understandable ways here.…

Continue Reading

This week, Daniel gives me an introduction to the strange world of the Southern Nationalists.

This week, Daniel gives me an introduction to the strange world of the Southern Nationalists.

It’s November 19th, 2016. Clean Bandit has debuted at number one with “Rockabye,” while Rae Sremmurd, Bruno Mars, James Arthur, and the Weeknd also chart. In news, the British Medical Journal calls for the legalization of drugs while Donald Trump agrees to pay $25m in settlements over Trump University.

It’s November 19th, 2016. Clean Bandit has debuted at number one with “Rockabye,” while Rae Sremmurd, Bruno Mars, James Arthur, and the Weeknd also chart. In news, the British Medical Journal calls for the legalization of drugs while Donald Trump agrees to pay $25m in settlements over Trump University.

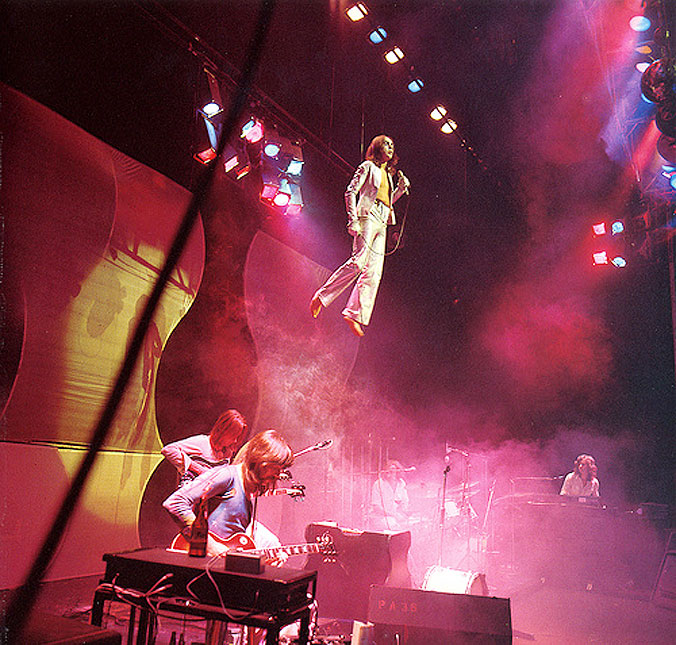

pluck from American music to make it big, Genesis came from a school of art that looked to its homeland for its stories. There’s a pastoral quality to much of their music that’s more at home in a tradition with As You Like It than The Great Gatsby. English land and politics come into Gabriel-era Genesis songs quite often, and Bush’s nurturing relationship with British mythos bears similarities to this approach (which will come to a crescendo in “O England My Lionheart”).…

pluck from American music to make it big, Genesis came from a school of art that looked to its homeland for its stories. There’s a pastoral quality to much of their music that’s more at home in a tradition with As You Like It than The Great Gatsby. English land and politics come into Gabriel-era Genesis songs quite often, and Bush’s nurturing relationship with British mythos bears similarities to this approach (which will come to a crescendo in “O England My Lionheart”).… It’s November 5

It’s November 5

It’s October 29th, 2016. Little Mix remain at number one. Actually, the second, third, fourth, and fifth songs on the chart do too. The news is altogether more volatile; Parliament approves the long-gestating Heathrow third runway project, which isn’t that big. In the US, meanwhile, the far-right militiamen who occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge earlier in the year are all acquitted and FBI Director James Comey makes a stunning intervention into the US Presidential race less than two weeks before election day as he announces the re-opening of the investigation into Hilary Clinton’s e-mails due to e-mails found on a device during the investigation of Anthony Weiner’s sexting of a fifteen year old girl while continuing not to disclose that Trump Campaign was also being investigated over its links to Russia. This has consequences.

It’s October 29th, 2016. Little Mix remain at number one. Actually, the second, third, fourth, and fifth songs on the chart do too. The news is altogether more volatile; Parliament approves the long-gestating Heathrow third runway project, which isn’t that big. In the US, meanwhile, the far-right militiamen who occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge earlier in the year are all acquitted and FBI Director James Comey makes a stunning intervention into the US Presidential race less than two weeks before election day as he announces the re-opening of the investigation into Hilary Clinton’s e-mails due to e-mails found on a device during the investigation of Anthony Weiner’s sexting of a fifteen year old girl while continuing not to disclose that Trump Campaign was also being investigated over its links to Russia. This has consequences.

on huge swaths of Bush’s work. She was subsequently instructed by Kemp in his dance classes, and he’s remained an influence on her work. Years later, Bush was still praising Kemp in interviews, and of course she paid her respects upon Kemp’s death last year. It’s easy to feel she never really got over that first performance of Flowers. This display of eroticism, veneration of physical beauty, and dedication to surrealism would remain useful to Bush, staying visible all the way from The Kick Inside to 50 Words for Snow.…

on huge swaths of Bush’s work. She was subsequently instructed by Kemp in his dance classes, and he’s remained an influence on her work. Years later, Bush was still praising Kemp in interviews, and of course she paid her respects upon Kemp’s death last year. It’s easy to feel she never really got over that first performance of Flowers. This display of eroticism, veneration of physical beauty, and dedication to surrealism would remain useful to Bush, staying visible all the way from The Kick Inside to 50 Words for Snow.…