To Think of a Way to Save Her (The Name of the Doctor)

|

| What do you mean it’s not back until next Christmas? |

|

| What do you mean it’s not back until next Christmas? |

Last time in ‘Summing Up’, we talked about how the right-libertarian “views the horror of socially-arranged altruism as worse than the horror of letting people die for want of medical care” because “libertarianism is against individual freedom for all because it depends upon collective liberation”. This, of course, raises another issue. Where does one draw the line? If socialised medicine is totalitarianism for doctors, why is the tacit threat of destitution which lies behind the wage labour system not considered equally bad? The answer to this question is the same brute and vulgar answer we gave already. It comes down to which side you’re on… which, most of the time, in an instance of capitalism creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of the selfish and cynical actor of its own ideological account of human nature, comes down to which class you’re in, or which class your interests are aligned with.

Last time in ‘Summing Up’, we talked about how the right-libertarian “views the horror of socially-arranged altruism as worse than the horror of letting people die for want of medical care” because “libertarianism is against individual freedom for all because it depends upon collective liberation”. This, of course, raises another issue. Where does one draw the line? If socialised medicine is totalitarianism for doctors, why is the tacit threat of destitution which lies behind the wage labour system not considered equally bad? The answer to this question is the same brute and vulgar answer we gave already. It comes down to which side you’re on… which, most of the time, in an instance of capitalism creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of the selfish and cynical actor of its own ideological account of human nature, comes down to which class you’re in, or which class your interests are aligned with.

Let’s pause again to notice all those ‘vons’ in the names of the great Austrians. And let’s also pause to again notice that, in applying such cynicism about human nature, such distrust of democracy, such a strategic splitting of the concept of freedom, and such naked class interests, the libertarians are, indeed, the heirs of the Founding Fathers – not just of the United States but also, as we’ve seen, of Ireton and Cromwell and the equivalent bourgeois revolutionaries in England. They carry many of the most fundamental imperatives of the founders of the bourgeois state into the present era.

The libertarians’ philosophical rationale for this partiality to the rights and privileges of the ruling class, and the attendant indifference to those of the working class, is that private property is the basis of liberty (to the extent that some have taken to rechristening them, far from unjustly, ‘propertarians’). But this philosophical rationale manages the impressive feat of being both a tautology and a contradiction. It’s a tautology because it assumes the point under question. It’s a contradiction because if private property, while conferring liberty on its possessors, also structurally curtails the liberty of the propertyless, then whither the concept of liberty… except as a luxury to be enjoyed by a few? From here the libertarian is inescapably pushed towards somehow justifying the inequity, towards explaining why yes, liberty is a luxury to be enjoyed by a few – and quite right too! And hence we get the various distinct but similar ways in which the different strands of this tradition of bourgeois thinking (libertarianism, classical liberalism, etc) have imported justifications in from outside, from conservatism. The justifications are easy to find. You need only look at the many and drastic specific inequities generated by capitalist society, generalise from them, and amputate history and context so that they appear to have no cause. That’s how you end up with libertarians and liberals enthusing over The Bell Curve, etc.

(The necessary amputation of context is actually especially striking in the case of the libertarians, because a whole host of the inequities they seize upon to justify hierarchy are based on the imperialism – or at least war – they profess to be against.…

|

| For the second episode running, the Doctor struggles to eat soup. |

It’s December 5th, 2015. Justin Bieber still has three songs in the top ten, with “Love Yourself” at number one. Wstrn, the Weeknd, and Grace featuring G-Eazy also chart, with Adele still in there too. In news, the United Nations Climate Change Conference convenes in Paris, beginning the process of the Paris accords. A terrorist attack in San Bernandino, California kills fourteen, while the UK begins air strikes in Syria following a parliamentary vote to authorize them.

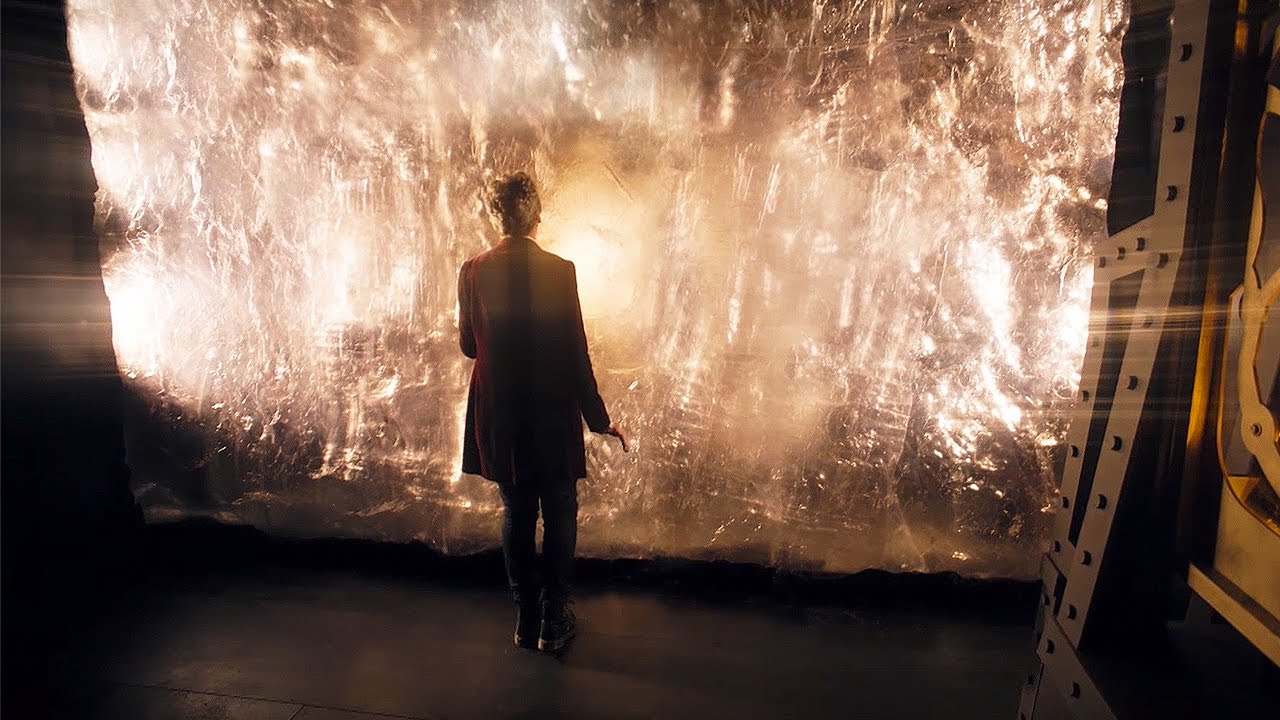

On television, meanwhile, Moffat’s masterpiece. This is, I imagine, a rather more controversial claim than last week. Sure, Hell Bent had a 2% higher AI rating than Heaven Sent, which means that it’s objectively as good as Kill the Moon and Aliens of London, but I don’t actually think that joke needs a punchline. The consensus here is clear: Heaven Sent is a brilliant and emotional triumph, while Hell Bent is a hot mess. To an extent I can’t even argue with this. Hell Bent is unequivocally messy, and it has Jenna Coleman in that blue-grey sweater. But many of my favorite Doctor Who stories are messy. Heck, possibly all of my favorite Doctor Who stories are messy.

Hell Bent, of course, is exceptionally so; a story that positively revels in the number of unrealized parallels and allusions it has going on, constantly seeming like it wants to foreshadow things it in reality has no intention of paying off. Beyond that, there is a willfully perverse sense of importance here. This is a story that brings to Moffat’s post-Day of the Doctor Gallifrey arc to a close with little more than a shrug, resurrects Rassilon for the sake of kicking him out of the story at the sixteen minute mark, radically redoes our entire idea of what the Matrix is to provide a neat horror setting for ten minutes in the middle, and concludes the entire hybrid plot with a shrug and a hand-wave. For people who don’t like it when Moffat does things like this—and obviously there are a fair number of them—this borders on trolling. Certainly when Moffat’s structural tics are being deployed at this scale and on the back of such an imperiously confident run as the last eighteen episodes it’s easier to read this as a decisive pair of middle fingers to the haters than as mere incompetence.

For those of us who have bought into Moffat’s idiosyncrasies, however, this is something altogether different. Moffat doesn’t decline to pay something off out of laziness; he does it to make a point about whatever it is he pays off in its stead. And he’s consistent in how that bait and switch works: he promises a grandiose epic of manpain and then offers an intensely human story, typically but not always about women. Within this framework, the question of what the story of Clara’s death would end up focusing on was a non-question: it would focus on Clara.…

In an article entitled ‘Democracy Isn’t Freedom’, Ron Paul wrote:

In an article entitled ‘Democracy Isn’t Freedom’, Ron Paul wrote:

Americans have been conditioned to accept the word “democracy” as a synonym for freedom, and thus to believe that democracy is unquestionably good.

The problem is that democracy is not freedom. Democracy is simply majoritarianism, which is inherently incompatible with real freedom. Our founding fathers clearly understood this, as evidenced not only by our republican constitutional system, but also by their writings in the Federalist Papers and elsewhere. James Madison cautioned that under a democratic government, “There is nothing to check the inducement to sacrifice the weaker party or the obnoxious individual.” John Adams argued that democracies merely grant revocable rights to citizens depending on the whims of the masses, while a republic exists to secure and protect pre-existing rights. Yet how many Americans know that the word “democracy” is found neither in the Constitution nor the Declaration of Independence, our very founding documents?

Now, an important thing to note here is that Paul is absolutely right. Most of the Founding Fathers did not envisage their new republic as a democracy. Indeed, Madison (as Chomsky is fond of reminding us) explicitly saw the task of designing the new government as one of designing a system which would protect “the minority of the opulent against the majority”. Chomsky also likes to quote John Jay as saying “The people who own the country ought to govern it”. As he writes in The Common Good,

Madison feared that a growing part of the population, suffering from the serious inequities of the society, would “secretly sigh for a more equal distribution of [life’s] blessings.” If they had democratic power, there’d be a danger they’d do something more than sigh. He discussed this quite explicitly at the Constitutional Convention, expressing his concern that the poor majority would use its power to bring about what we would now call land reform.

So he designed a system that made sure democracy couldn’t function. He placed power in the hands of the “more capable set of men,” those who hold “the wealth of the nation.” Other citizens were to be marginalized and factionalized in various ways, which have taken a variety of forms over the years: fractured political constituencies, barriers against unified working-class action and cooperation, exploitation of ethnic and racial conflicts, etc.

This is nothing surprising. We can go back to the dawn of bourgeois democracy in England, the Putney Debates, and see the bafflement which enveloped Ireton and the other Parliament Men when Rainsborough and the Levellers demanded that every man should have a say in the government that ruled over him, even if he lacked a “permanent interest” (i.e. property). Ireton and his fellow propertied gentlemen not only didn’t agree with such a concept – they couldn’t even comprehend it. It was utterly alien to them. The very radical ideas thrown up by the revolution they had led were now confronting them, shouted from the mouths of the common men they’d relied on as their muscle, and they might as well have been speaking a foreign language.…

|

| I got a rock. |

It’s November 28th, 2015. Justin Bieber continues his assault on the top ten, holding number one with “Sorry” while “Love Yourself” and “What Do You Mean” are also in the top ten. One Direction and Nathan Sykes also chart. In news, a gunman attacks a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs and Turkey shoots down a Russian jet on the Syrian border, sparking a bit of an international incident.

On television, meanwhile, Moffat’s masterpiece. Which means that we should start by talking about Blink, the story to which any supposed Moffat masterpiece must be compared. It is not that Blink is straightforwardly and unquestionably the best Moffat story; picking The Pandorica Opens/The Big Bang or Day of the Doctor is an eminently respectable choice. But a masterpiece is different from a mere best, implying not just raw quality but a sort of technical proficiency that shows off the writer’s skill. This is why Blink serves as the type specimen for Moffat—a story long on formal constraint and ostentatiously clever structure that plays elaborate games with time and causality. Its ostentatious grandeur hangs over the whole Moffat era, a high watermark whose reputation seems to foreclose the possibility of ever topping it.

And yet Heaven Sent brazenly tries to. This is clear from the basic technical premise: a one-hander, in which Peter Capaldi is left to carry an entire fifty-five minute episode by himself, with no co-stars save for a silent monster, a cameo by Jenna Coleman, and a young boy with no dialogue in the cliffhanger. Where Blink was a doctor-lite episode, Heaven Sent is its radical opposite, an episode that is not so much Doctor-heavy as it is Doctor-exclusive. There’s an almost petulant quality to the anxiety over self-plagiarism, a sense that in going to the opposite extreme Moffat has only confirmed the validity of the comparison. But what is perhaps more telling is the nature of the technical challenge laid out. Blink existed because of a scheduling challenge, minimizing the Doctor’s appearances so it could be double blocked with Human Nature/Family of Blood, Heaven Sent is a one-hander for no reason other than to be impressive. It’s not a clever solution to a production problem; it’s clever because the show wants to be appreciated for how clever it is.

Is this arrogant? Narcissistic? Self-congratulatory? Yes, of course it is. There is no point in pretending that Heaven Sent is not an exercise in vanity that seeks to put a final and decisive triumph on Moffat’s record before he departs. That it unequivocally succeeds does not change the task in question. But we’ve kind of buried the main point in all of that. Heaven Sent is a story that only makes sense in the context of Moffat’s presumptive departure. Its presence in the season is a crystal clear sign that he’s reaching the end of what he has to say about Doctor Who. This can hardly be called a surprise. He’s already done a season more than Davies, and somewhere in the midst of The Zygon Inversion he surpassed Robert Holmes for total minutes of Doctor Who written over the course of his career.…

“There has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism. Not even Doctor Who.”

“There has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism. Not even Doctor Who.”

– Walter Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’ (quoted from memory)

*

Where was I?

Oh yeah, it’s unfair to pick on ‘Talons of Weng-Chiang’ for being racist because all Doctor Who is racist.

So what do I mean by that?

Well, I don’t just mean that there are lots of stories in Doctor Who that contain implicit or explicit racist ideas, representations, or implications … though it does, and it might be worth going through some of them.

There’s ‘An Unearthly Child’, for instance, which associates ‘tribal’ life with brutishness and savagery, and suggests that tribal people need to be taught concepts like friendship and cooperation by enlightened Western liberals from technologically advanced societies… as if, historically, enlightened Western liberals from technologically advanced societies haven’t been the ones slaughtering tribal peoples. Native peoples, by the way, know what friendship and cooperation are. Sometimes better than us. And we are talking about native peoples in ‘Unearthly’. Because of Europeans’ historic encounters with native peoples as European imperialism and colonialism spread across the globe, we’ve come to associate the notion of tribal people – if we accept that word and what it connotes – with people of colour. And such people, after initial encounters (often amiable), became conveniently reconstructed in the ideological thoughtworld of European imperialism and colonialism as, to borrow Kipling’s phrase, “half devil and half child”. This couplet neatly describes the Tribe of Gum, and shows them to be imagined out of the imperialist ideological tradition. Even if, in an alternative reading, they are the descendants of the people of the 1960s after a nuclear holocaust, they are still a picture of humanity in a savage ‘state of nature’, itself part of the same ideological tradition.

This is a very early indication of the complexity of the issue. Without any overt racial statement or coding, the very first story is found to be an ideological product of a racist tradition arising from imperialism and colonialism.

Then there’s ‘The Daleks’, an almost immediate engagement on the part of the show with something that will continue to be one of its running fixations: the metaphorical representation of Nazism. This story introduces the show’s ubermensch uber-villains, well understood to be metaphorical Nazis, with their creed of racial supremacy and their cries of “Exterminate!” (though they don’t actually do that in their debut), and takes a more or less explicit anti-racist line on its surface. It goes beyond a conventional post-war British triumphalism and explicitly associates Nazism with racism… or at least with its own understanding of racism as a form of parochialism, which chimes with a certain way of interpreting post-Windrush tension in the UK. The irony is that, almost behind its own back, this is a story in which “perfect”, virtuous, blonde, volkisch, Aryan, supermen-farmers are forced to fight a race of evil, mechanically-ingenious, wealth-hoarding, subterranean dwarves who threaten their culture.…

All right. Since we finally have an airdate announced, it’s probably time to formalize Eruditorum Press’s plans for Series 11. As usual, our hope is to do reviews and podcasts of all ten episodes and the Christmas special. And I mean, we really hope to do that. I’m dying to weigh in week by week on a new era of Doctor Who. It sounds amazing. But, of course, bills must be paid, and so there are some Patreon goals we have to meet first. At the time of writing, the Patreon is at $371 a week, just $4 shy of the $375 threshold at which I’ll review every episode. So one $5 pledge is all it’ll take to make sure that happens. And I’ve just made an AMA post for $5 patrons, so it’s the perfect time to do that.

Podcasts are a little more ambitious, at $400. We might not make that; it’d be the highest the Patreon has ever gone, certainly. But I am an optimistic devil, and I think we can probably just squeak through at that level. So. If you want to hear me round up ten awesome guests and talk about Doctor Who with them, get thee to the Patreon.

If reviews happen, I’m going to pause the Capaldi Eruditorum entries for ten weeks. The post that will go up on October 1st is a perfect point to pause for a bit, and I think doing so is the right decision for my mental health and productivity. I’ve been on a grueling production schedule and literally everything is behind, and while I’d love to double run reviews and Eruditorum entries, the reality is that I’d be wiser to let myself do reviews in the first couple days of the week and then have the remainder of the week to work on getting books reissued, revise Eruditorum v7, and make there ever be anohter Last War in Albion post ever. So if we hit reviews, I’ll write them as fast as I can, send them out to Patrons, and then put them on the site either Tuesday or Wednesday depending on when I’m getting the out to Patrrons because I want them to still get a nice window of exclusivity that makes ’em feel all special and shit.

Finally, I want to just do that obnoxious thing where I get all personal and sentimental. So first of all, thank you to all my Patrons. I love that I can do this job. It’s one of the most amazing experiences of my life. That said, the summer has been really rough financially. It’s not some sort of dire “The GoFundMe will start imminently” situation, but it’s rough ehough that theres a good chance I’m going to need to use the v8 Kickstarter to fund the fulfillment of the v7 one. This isn’t because of a drying up in Patrons or anything—the Patreon is doing the best it ever has. It’s just a combination of some bad luck and the fact that completly replacing your entire wardrobe from scratch, picking up a bunch of new medical appointments, getting shot in the chin with lasers, and starting to smear a bunch of weird colorful rocks on your face every morning costs money.…

|

|

List of ways companions have died on Doctor Who: asphyxiated in space, instantaneously aged to death by the Time Destroyer, spaceship crashed into Earth, a bird flew into her tits |

It’s November 21st, 2015. Justin Bieber’s “Sorry” has unseated “Hello” at number one, with both “Love Yourself” and “What Do You Mean” also in the charts. Jess Glynne and One Direction are also newly in the top ten. In news, Storm Barney strikes Britain, knocking out thousands of people’s power, and not a ton else happens unless you find Bobby Jindal withdrawing from the 2016 presidential election interesting, which you probably shouldn’t.

While on television, the Doctor Who debut of Sarah Dollard. “What’s the most impressive debut of a Doctor Who writer” is a fairly entertaining parlor game. Harness has obvious cred, as does Mathieson. There’s a host of obvious one hit wonders to consider: Peter Ling, Andrew Smith, or Barbara Clegg. There are big classics like Terry Nation, Malcolm Hulke, or even Steven Moffat himself. Or you could go with an impishly perverse choice like Stephen Wyatt. But for the most part the debate’s plausible margin of error evaporates here. Face the Raven may not be the best first story anyone has ever written for Doctor Who, but it is the one in which the fact that it’s a debut is most impressive.

The biggest and most obvious thing to point out is the writing credit. “Sarah Dollard.” Not “Sarah Dollard and Steven Moffat.” In a period where Moffat is willing to take credit for even small contributions such as his work on The Caretaker, his absence here speaks volumes. Sure, we could be cynial and suggest that Moffat was simply aware of the bad optics of publicly rewriting what is only his second female writer, but if you look at the scene you’d most expect Moffat to need to intervene on, the pre-death scene, it doesn’t sound like him. He’d write it differently; there would be eminently quotable lines aching with cleverness. It’d be brilliant, of course, but it wouldn’t be this particular flavor of brilliance. This isn’t Moffat; this is a new voice being shoved out onto the biggest stage imaginable and giving it her absolute all.

What’s remarkable in all of this is the amount of confidence and trust placed in Dollard, who saw her “trap streets are real” pitch get both Me and the death of Clara added to it. In another era, this sort of layering of added requirements on a relatively green writer got you Time-Flight at best and The Twin Dilemma at worst. This is both an overstuffed banquet and an absolute lynchpin story that you’d expect to go to either a trusted veteran or someone like Phil Ford who was clearly just there to save Moffat the time of a first draft. Instead it goes to the rookie who, it must be stressed, hits it out of the park.

Let’s start with the big ticket item: the death of Clara.…

Thanks to the various people who looked over this and made suggestions, especially Holly. The mistakes are, of course, mine alone.

Thanks to the various people who looked over this and made suggestions, especially Holly. The mistakes are, of course, mine alone.

This post was originally going to have the alternative title ‘Why I’m No Longer Talking to Doctor Who Fans About Race’ but Andrew Rilstone got there before me, damn his eyes. Seriously, go read Andrew’s post because it’s excellent. Amongst other things, he looks directly at the arguments put forward in Marcus Hearn’s Doctor Who Magazine editorial. Which is, of course, what started this.

*

We live in a strange world. I’m being told, on the one hand, that Jeremy Corbyn, the most consistently and committedly anti-racist MP in the Commons, is an antisemite, and, on the other, that ‘Talons of Weng-Chiang’, a story in which a Fu Manchu style villain – played by a white actor in rubber ‘yellowface’ – abducts white women with the help of a Tong of “opium sodden” Chinese cultists working out of Limehouse, isn’t racist. You just know, don’t you, that some professional Doctor Who hacks are convinced that Corbyn, if elected, would institute Britain’s very own reenactment of the Final Solution, but will also quibble with you over whether or not Julius Silverstein, the rich, greedy, grasping, paranoid collector in ‘The Web of Fear’ is problematic or not.

Gee, it’s almost like there is something profoundly, foundationally wrong with our discourse on the subject of race and racism. The problems in Doctor Who fandom are a tiny – if microcosmic – part of this wider problem. But Doctor Who fandom is one of the places I come from. And they picked on my friend. So here we are.

I won’t say much about the specifics of the kerfuffle which led me to write this. Apart from anything else, it’s just another irruption of the same running argument that Doctor Who fans have been having about ‘Talons of Weng-Chiang’ for quite some time. El and I, both veterans of Gallifrey Base, were together involved in at least one previous such irruption a few years ago, during which some forum posters – and I shit you not – actually stated that they felt John Bennett’s make-up was realistic. As I noted at the time, being bothered by the rat but not by the yellowface is one thing, but

…it’s yet another quantum leap to the point where you find the rat unconvincing but not the yellowface. And you’re prepared to say so in public. This reveals a shameless thoughtlessness, a terrifying absence of self-examination, an arrogance born of privilege. And it also seems to reveal a willingness not simply to be unconcerned by the monstering of a whole race of people, not simply to delude yourself that its not happening in the text (because you’ve never bothered to avail yourself of the myriad opportunities now freely available to anyone with internet access to educate yourself about how representations of people work in the texts you consume) but to actually think that the representations (of, say, Chinese people as expressionless, rubberfaced bogeymen) are accurate and true to life.

|

| Jeez man most people just use a sleep blindfold |

It’s November 14th, 2015. Adele is at number one with “Hello.” Fleur East, Wstrn, and Justin Bieber also chart, the latter with both “Sorry” and “What Do You Mean.” In news, a series of terrorist attacks take place in Paris including a mass shooting at the Bataclan theatre during an Eagles of Death Metal concert and a series of suicide bombings around the Stade de France during a match between France and Germany. The first storm named by the Met Office, the extratropical cyclone Abigail, hits Scotland, while a series of protests at the University of Missouri lead to the resignation of the president of the system.

On television, meanwhile, a distinctly unusual episode of Doctor Who. Sleep No More is not, by general acclamation, a classic. Even those inclined towards sympathy for Gatiss tend to focus their redemptive efforts elsewhere. And it’s easy enough to see why this might be. It’s a decidedly lumpy story with idiosyncratic pacing that never quite sells its stakes or offers a coherent account of its concept. Character remains something of an afterthought for Gatiss, which is frustrating for Clara’s last straightforward adventure in a season that broadly underutilized her, and doubly so given that Gatiss has written flat-out great scenes for her in the past. But several of those things are just snooty ways of rephrasing “it was written by Mark Gatiss,” and the rest are products of the fact that it’s doing several other interesting things instead.

So having gently and lovingly placed The Zygon Invasion/The Zygon Inversion in the path of an oncoming bus, let’s do that other thing we periodically do and dust off an unpopular story to explain why it’s got more going on than you might think. Because while defending Sleep No More as an overlooked classic in a season with The Magician’s Apprentice/The Witch’s Familiar, The Girl Who Died, The Zygon Invasion/The Zygon Inversion, Face the Raven, Heaven Sent, and Hell Bent is probably a bit of a reach, slamming it as a bust is, or at least should be, just as ridiculous. This is a story that’s long on ambition, achieves no small part of it, and comes off as a lot more in step with its times than it might have appeared in late 2015.

Let’s start with what this story is doing. Most obviously, it’s a found footage horror story. This is not ambitious in and of itself—it’s just another genre swipe of the sort that Doctor Who can at baseline be expected to do. But what’s interesting is that it’s a genre largely defined by technical concerns as opposed to content-based ones. There are a few constraints on what happens in a found footage horror story; it’s assumed that things will end with some destructive event that leaves the footage as the only remaining record of whatever happened, but past that there aren’t a ton of tropes that define the genre.…