Some Magic Buried Deep in My Heart (Take to the Sky)

Take to the Sky (TV performance, 1998)

Take to the Sky (webcast, 2001)

Take to the Sky (TV performance, 2002)

Take to the Sky (official bootleg, 2005)

Take to the Sky (official bootleg, 2007)

Take to the Sky/Datura (webcast, 2014)

In the wounded aftermath of Y Kant Tori Read, with Atlantic demanding a new record on about six months turnaround, Amos was invited over by her high school friend Cindy Marble, who was living in LA also failing to make it in the music industry. Marble had a piano at her place, and Amos, who had gotten rid of her own piano during her excursion as a rock chick, sat down to play, finding herself so utterly engrossed by her old instrument that she lost track of hours and of Marble. Marble implored her to take the instrument back up, arguing that this was the setting in which Amos felt authentic and genuine. And so Amos rented a piano for the apartment she was sharing with her boyfriend/producer Eric Rosse and began to write.

Unsurprisingly, she began with a song that grappled with her failure. “Take to the Sky,” called “Russia” in its earliest demos, is unrepentantly a rewrite of history in which Amos casts herself as a luckless prisoner of other people’s agendas—”you got me moving in a circle,” she complains, and laments that she’s “so close to touching freedom / then I hear the guards call my name.” As we’ve seen, Amos was far more deeply enmeshed in her role than is convenient for the story she’s telling here. But in this case, Amos pulls off the classic trick of making it all up and having it come true anyway. While she may be fudging the details on how exactly things went wrong, the song is ultimately focused not on a forensic examination of why her previous album sucked but on depicting her own internal landscape in its wake. And so we get a pre-chorus in which Amos offers a litany of heckling voices: “And my priest says / ‘you ain’t saving no souls’ / my father says / ‘you ain’t making any money’ / my doctor says / ‘you just took it to the limit’/ and I stand here / with a sword in my hand,” her once prominent prop hanging limply, dumbstruck by her side.

From here, Amos launches her attack, staring down her critics, which is to say everyone. “You can say it one more ti-yime / what you don’t like. / Let me hear it one more time” she belts, before pivoting to her defiant conclusion: ”then take a seat while I / take to the sky.” It’s simple—far simpler than the versions of the sentiment she’ll express in the next couple of songs that she writes. Indeed, it’s easy to see why this ended up as a b-side: it’s solid and catchy song, but its unambiguous earnestness would have jarred on Little Earthquakes itself, where Amos’s reclamations of self run more towards the bittersweet than the anthemic. Forcing this to share immediate space with “Crucify,” “Silent All These Years,” “Little Earthquakes,” or (gods) “Me and a Gun” would have cheapened both.

But as a statement of intent from an artist who was beginning to write Little Earthquakes, “Take to the Sky” is compelling. Part of this, of course, is that we have the benefit of hindsight and can confirm that it all worked out exactly as Amos predicted: the haters took a seat while she soared to the artistic heavens. It ain’t bragging if it’s true. There’s a pronounce immaturity in “Take to the Sky” compared even to the other songs she cut in the initial Davitt Sigerson sessions for the album, but positioned at the outset of the project, the heady brashness of its boast justifies itself. Little Earthquakes is enriched by the hard-fought confidence with which Amos approached it.

But while “Take to the Sky” is made a deeper experience by knowledge of why there’s a sword in her hand and an understanding of what her flight path turned out to be, it scarcely needs either to work. Empowering swagger may be a simpler pleasure than expressing the nuances of post-traumatic identity, but there’s a reason it’s a mainstay of female-fronted pop music. Amos’s take on it is, as you’d expect, slightly too strange to ever be drafted into the campaign playlist of a female politician, but it’s an effective execution of the empowerment song genre.

Its best trick is played at the one second mark, as Amos provides her own percussion section by slapping the wood of her piano. The effect is immediately arresting— a “bomp bomp *WHAM*” as two banged out chords deep into the bass register of the piano are followed by the first hit of the makeshift drum. It’s not a complex piano line by any stretch of the imagination—you could learn to play it in an hour even if you’ve never touched the instrument before—it took me about a minute to get it down having not seriously played in a decade and never having been what you’d call “good.” But this is deceptive—its deftness is in how well it uses the instrument, not in how difficult it is to play. (See also the “Come As You Are” riff, which was both one of the best guitar riffs of 1992 and also what a decade’s worth of teenagers learned in their first guitar lessons.) Amos is using her whole instrument, a physical performance that treats the piano not as a set of keys but as a coherent object whose outer frame is as much a part of the instrument as the rest of it. I don’t mean to over-mystify whacking the side of a piano with your hand or to suggest that it’s an unprecedented trick—it’s not. But it’s a trick that speaks to how central the piano is to Amos, and how much her range of expression had been cut down when she misguidedly rebranded herself as more or less a pure vocalist.

The song has a similar neat trick musically. It’s in A minor, but the overwhelming majority of chords throughout the song eliminate the third. The big opening riff moves from an A5 to C5 to D5, and this cycle makes up the bulk of the song. The prechorus and chorus add commplexity—the prechorus swings from a D7 to an Am7, while the chorus itself sticks to the major chords of the key, but when it comes time to resolve it all with the title line the song returns to its power chords with an A5. So while the song is in a minor key, there are precious few actual minor chords in it–the only one is that Am7 in the prechorus, which provides a false resolution on “with a sword in my hand” before the major chords kick back in. The result is an empowerment song that doesn’t ever quite give an emphatic resolution. When it ends, it’s on a suspended synth pad that hangs around on a D5 for a half-second after the rest of the song abruptly cuts out, a chord that does not resolve anything. But this is fitting. “Take to the Sky is Amos’s liftoff; in the end, it’s her flight that will justify her.

Recorded in Los Angeles at Capitol Records in 1990, produced by Davitt Sigerson. Video directed by Cindy Palmano. Released on the “Winter” single in 1992, and played live throughout Amos’s career.

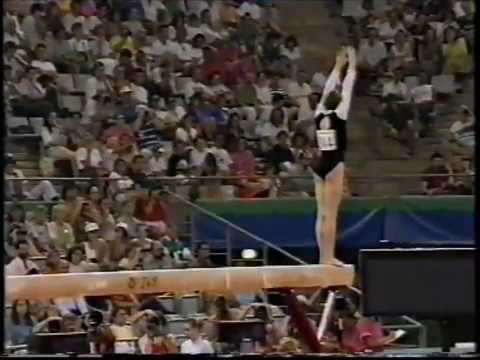

Top: Tatiana Lysenko on the beam at the 1992 Oympics.

Take to the Sky (1992)

Take to the Sky (1992)

October 7, 2019 @ 9:55 pm

Amos pulls off the classic trick of making it all up and having it come true anyway.

I hear that’s the funny part.