Impossible Girl (Hell Bent)

|

| For the second episode running, the Doctor struggles to eat soup. |

It’s December 5th, 2015. Justin Bieber still has three songs in the top ten, with “Love Yourself” at number one. Wstrn, the Weeknd, and Grace featuring G-Eazy also chart, with Adele still in there too. In news, the United Nations Climate Change Conference convenes in Paris, beginning the process of the Paris accords. A terrorist attack in San Bernandino, California kills fourteen, while the UK begins air strikes in Syria following a parliamentary vote to authorize them.

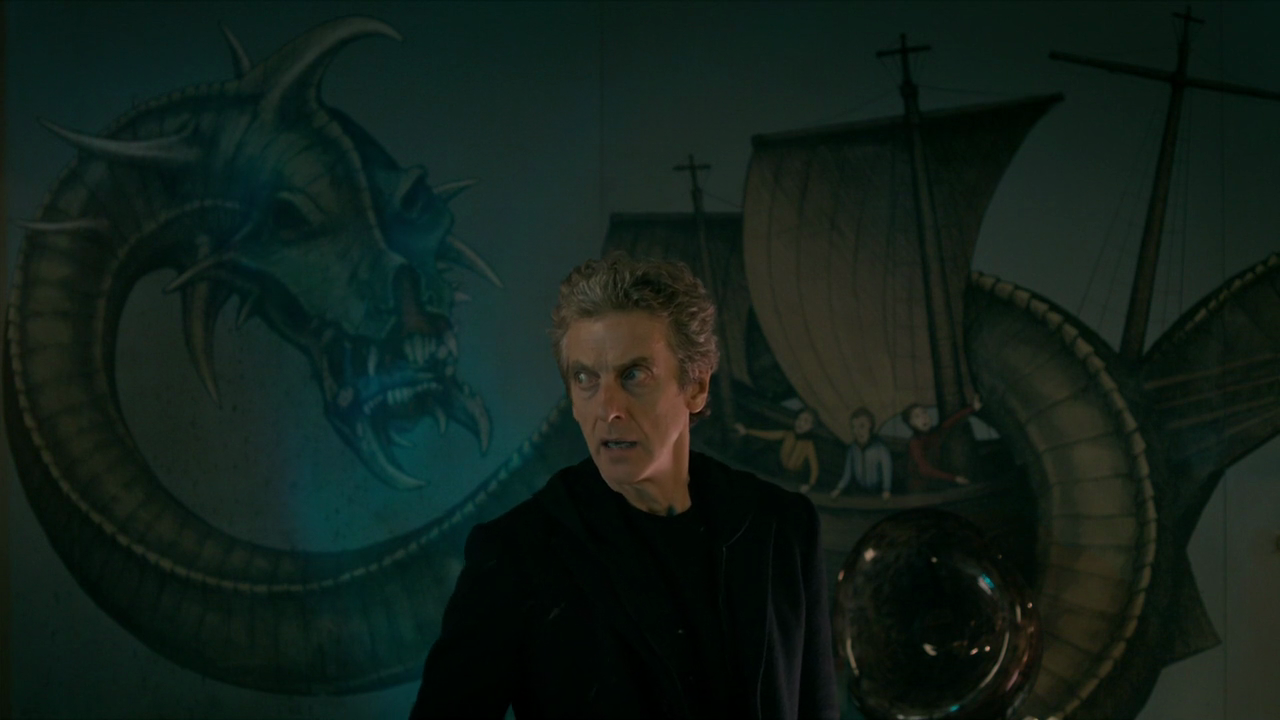

On television, meanwhile, Moffat’s masterpiece. This is, I imagine, a rather more controversial claim than last week. Sure, Hell Bent had a 2% higher AI rating than Heaven Sent, which means that it’s objectively as good as Kill the Moon and Aliens of London, but I don’t actually think that joke needs a punchline. The consensus here is clear: Heaven Sent is a brilliant and emotional triumph, while Hell Bent is a hot mess. To an extent I can’t even argue with this. Hell Bent is unequivocally messy, and it has Jenna Coleman in that blue-grey sweater. But many of my favorite Doctor Who stories are messy. Heck, possibly all of my favorite Doctor Who stories are messy.

Hell Bent, of course, is exceptionally so; a story that positively revels in the number of unrealized parallels and allusions it has going on, constantly seeming like it wants to foreshadow things it in reality has no intention of paying off. Beyond that, there is a willfully perverse sense of importance here. This is a story that brings to Moffat’s post-Day of the Doctor Gallifrey arc to a close with little more than a shrug, resurrects Rassilon for the sake of kicking him out of the story at the sixteen minute mark, radically redoes our entire idea of what the Matrix is to provide a neat horror setting for ten minutes in the middle, and concludes the entire hybrid plot with a shrug and a hand-wave. For people who don’t like it when Moffat does things like this—and obviously there are a fair number of them—this borders on trolling. Certainly when Moffat’s structural tics are being deployed at this scale and on the back of such an imperiously confident run as the last eighteen episodes it’s easier to read this as a decisive pair of middle fingers to the haters than as mere incompetence.

For those of us who have bought into Moffat’s idiosyncrasies, however, this is something altogether different. Moffat doesn’t decline to pay something off out of laziness; he does it to make a point about whatever it is he pays off in its stead. And he’s consistent in how that bait and switch works: he promises a grandiose epic of manpain and then offers an intensely human story, typically but not always about women. Within this framework, the question of what the story of Clara’s death would end up focusing on was a non-question: it would focus on Clara.…

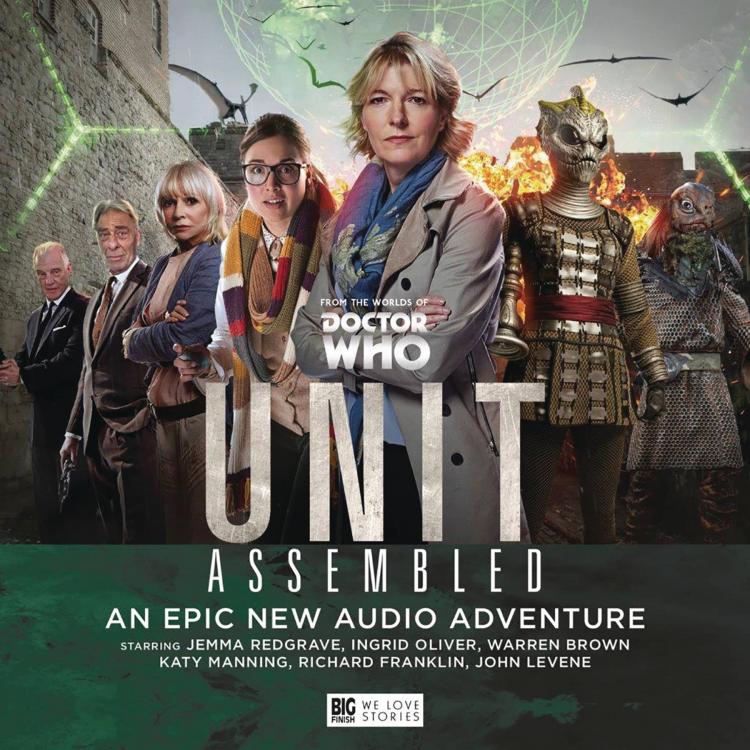

It’s been nearly five years since I last wrote about Big Finish on this site. Much of this gap is due to the fact that it’s only fairly recently that Big Finish’s license was expanded to cover the new series, so there’s been pretty slim pickings post-McGann. But in 2015 Big Finish released their first Torchwood and UNIT audios, and since then new series-adjacent material has been a mainstay of their increasingly bloated line. To date there’s nothing that directly ties into the Capaldi era, but as all of Osgood’s stories and all but one of Kate Stewart’s have Capaldi in them, this seemed the line to check back in on the company with.

It’s been nearly five years since I last wrote about Big Finish on this site. Much of this gap is due to the fact that it’s only fairly recently that Big Finish’s license was expanded to cover the new series, so there’s been pretty slim pickings post-McGann. But in 2015 Big Finish released their first Torchwood and UNIT audios, and since then new series-adjacent material has been a mainstay of their increasingly bloated line. To date there’s nothing that directly ties into the Capaldi era, but as all of Osgood’s stories and all but one of Kate Stewart’s have Capaldi in them, this seemed the line to check back in on the company with.

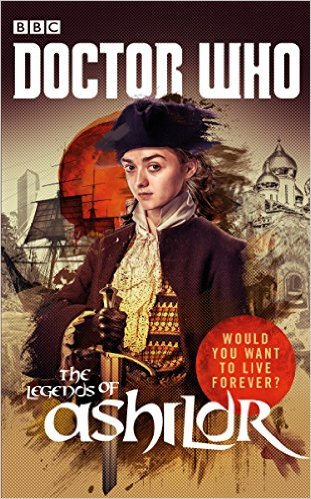

For all that we’ve been picking on the inadequacies of the standard book line, there had been efforts in the background to try new things. For a variety of reasons we didn’t cover efforts like Summer Falls and The Angel’s Kiss in the late Matt Smith era (actually just one reason, which was me saving things for the book), but they certainly represented one effort to change what the book line can and should do. The Legends of Ashildr represents a stab at another possible shape the books could take—anthologies of several short stories. Obviously there are some constraints around this. Just dumping a couple Doctor Who short story collections a year is an invitation for mediocrity with no obvious sales hooks. Whatever one might say about Big Bang Generation, it at least has a hook you can sell it with in a way that wouldn’t be true of a straightforward collection of shorts.

For all that we’ve been picking on the inadequacies of the standard book line, there had been efforts in the background to try new things. For a variety of reasons we didn’t cover efforts like Summer Falls and The Angel’s Kiss in the late Matt Smith era (actually just one reason, which was me saving things for the book), but they certainly represented one effort to change what the book line can and should do. The Legends of Ashildr represents a stab at another possible shape the books could take—anthologies of several short stories. Obviously there are some constraints around this. Just dumping a couple Doctor Who short story collections a year is an invitation for mediocrity with no obvious sales hooks. Whatever one might say about Big Bang Generation, it at least has a hook you can sell it with in a way that wouldn’t be true of a straightforward collection of shorts.