Ars Specula: Humans/Ex Machina (plus Mr Robot)

Artificial (adj.)

- made by human skill

- imitation; substitute

- pretended; contrived; feigned

- lacking in spontaneity; affected

- (biology) relating to superficial characteristics not based on the interrelationships of organisms

— from Latin artificialis, “of or belonging to art,” from artificium (see artifice).

Artifice (n.)

- a clever trick or stratagem; a cunning, crafty device

- crafty or subtle deception; trickery; guile

- ingenuity; skill; inventiveness

— from Latin ars, “art,” + facere, “do, make”

As Above, So Below

Ex Machina, written and directed by Alex Garland, is a slick and intellectual film that charts the journey of Caleb Smith, a computer programmer for a Googlish company who’s won a “lottery” that grants him an invitation to the northern retreat of the company’s founder, the grotesquely hypermasculine (and misogynist) Nathan Bateman. Nathan wants Caleb to perform a Turing Test over the course of one  week on his latest creation, an android named Ava who seemingly possesses artificial intelligence. Each day, Caleb interrogates Ava in a numbered “session,” made apparent to us through the use of interstitial title cards. Caleb dutifully examines Ava, then reflects afterwards with Nathan, conversations which serve to flesh out some of the film’s themes, ranging from art to human nature.

week on his latest creation, an android named Ava who seemingly possesses artificial intelligence. Each day, Caleb interrogates Ava in a numbered “session,” made apparent to us through the use of interstitial title cards. Caleb dutifully examines Ava, then reflects afterwards with Nathan, conversations which serve to flesh out some of the film’s themes, ranging from art to human nature.

Humans, on the other hand, is the first season of a British/American adaptation of a Swedish TV show, Real Humans. Set in the near future, “Synths” have become a ubiquitous labor force around the world, seemingly human but lacking the consciousness typically associated with “humanity.” Well, except for a select few, who are on the run from the ruthless hunter Hobb, a former engineer on the Synth project now employed by capitalist patrons. Humans charts the intersection of these conscious Synths with the dysfunctional Hawkins family, with a particular focus on the mother, Laura, the emotional heart of the show played brilliantly by Katherine Parkinson.

Even though both shows are rather different on the surface — one is practically an arthouse movie, the other an ongoing serialized drama that’s still got at least one more season up its sleeve — they do share much in common. In particular, the construction of their narratives reflect their conceptions of Artificial Intelligence.

In Ex Machina, the emphasis of artificial intelligence is on artifice and rationality, a thinking movie about thinking. It introduces its themes by posing the question of whether Ava can “pass” the Turing Test, which is typically conceived as an interaction between a human and a machine where the human never realizes they’re speaking with a machine. The very idea of the Turing Test is based in language, equating the manipulation of words and symbols with “intelligence” and hence sentience. Here, though, there’s a twist: Caleb is fully aware that Ava is a machine, which makes the challenge even greater – can she convince him of her sentience despite this disclosure?

This stripping away of artifice is reflected in the aesthetics of Ava’s special effects. We see through her limbs and torso that there’s machinery inside; Ava is made not just of metal, but glass and translucent plastic. And indeed, the whole of Nathan’s facility reflects this aesthetic – it’s very modernistic, with endless sheets of glass through which to peer. The direction is very studious, with carefully planned shots and precise editing.  Combined with the fact the story is rooted in intellectual conversation, Ex Machina ends up unifying the fabula of the story’s central conceits and the telling of that story (its “discourse”) into a coherent whole. One therefore might say that the film itself exhibits a kind of self-consciousness.

Combined with the fact the story is rooted in intellectual conversation, Ex Machina ends up unifying the fabula of the story’s central conceits and the telling of that story (its “discourse”) into a coherent whole. One therefore might say that the film itself exhibits a kind of self-consciousness.

But more telling is how the characterization unfolds. Every character is deceitful. Caleb never won a lottery for this opportunity, and neither did Nathan pick Caleb because he was an exceptional programmer; no, Caleb was picked because Ava’s design was particularly suited to Caleb’s “porn profile.” Caleb, on the other hand, exercises deception in his plan to get Nathan drunk and hack the computers. Ava’s deceit is that she really is pretending to like Caleb, as well as knowing more than she lets on – she’s the one responsible for the facility’s “power outages” (what a lovely metaphor). Even Nathan’s “assistant,” Kyoko, is a deceptive: she is only revealed later to be an android herself, pretending to be a mute subservient woman until then. In the end, Ava ends up tricking Caleb, locking him inside the facility after she’s killed Nathan, the better to facilitate her permanent escape.

This final twist likewise represents an act of deception on the part of the film itself. We have been anticipating a happy ending for Caleb, given both how he functions as the primary focal character in this small opera, and from his seeming heroic qualities by virtue of his helping Ava to escape, and so his demise comes across as unnecessarily cruel and out of the blue, as a shocking twist – we have almost no indication until then that Ava’s attitude towards him is antagonistic, largely because for most the film her POV is withheld from us.

So in Ex Machina, it seems, “sentience” is defined primarily not just as an intellectual endeavor, but one that hinges on deception. It’s a play on fallor ergo sum, or “I am mistaken, therefore I am,” as posited by St Augustine some 1200 years ago. Totally fundamental to who we are is the notion that we understand that we don’t know, and so we are obsessed to gain knowledge. Which, again, is an intellectual endeavor, driven primarily by our ability to reason.

Humans, on the other hand, conceives of AI as being rooted in the ability to feel, to have emotional responses, particularly those of pain and pleasure. Sentio ergo sum would be its motto. The conscious Synths know they are conscious because of their emotions. And so Humans is constructed as a serialized drama, rooted in relationships, emotional difficulties, and hang-ups. The central conceit of the show is ultimately the family.

And so its structure and content is that of a soap opera. Through serialized episodic storytelling, we find marriages falling apart, horny teenagers, problematic caregiving, infidelity, and guilt. The Synths themselves were created by David Elster, a man trying to cope with his own family issues: his wife was going mad, so he created caregivers for his son. Then his son Leo died, but David revived him through Synth technology, technology that extends to Leo’s consciousness, specifically to the technological storage and retrieval of memories. When David’s wife Beatrice commited suicide, he created a replacement, but Leo’s rejection of her led her to estrange herself from the rest of the Elsters, driving David to his own suicide. The emotional issues of the characters, both human and Synth, are what drives the story and shapes the narrative.

And so its structure and content is that of a soap opera. Through serialized episodic storytelling, we find marriages falling apart, horny teenagers, problematic caregiving, infidelity, and guilt. The Synths themselves were created by David Elster, a man trying to cope with his own family issues: his wife was going mad, so he created caregivers for his son. Then his son Leo died, but David revived him through Synth technology, technology that extends to Leo’s consciousness, specifically to the technological storage and retrieval of memories. When David’s wife Beatrice commited suicide, he created a replacement, but Leo’s rejection of her led her to estrange herself from the rest of the Elsters, driving David to his own suicide. The emotional issues of the characters, both human and Synth, are what drives the story and shapes the narrative.

Interestingly, the real-world work of neuroscientists like Antonio Damasio has begun to point to emotions and feelings as what actually creates consciousness in human beings, and possibly by extension in other life, too. Which is far different from the Wittgensteinian language-games of early AI research, as reflected in Ex Machina. But this rather raises the question of whether these shows are truly exploring the issues of Artificial Intelligence at all, so much as exploring the nature of human consciousness, of what it means to be human as opposed to transhuman. In other words, are these shows actually holding up a mirror to ourselves rather than pointing a telescope to the future?

Through a Glass Darkly

At this point I must point out that both Ex Machina and Humans share an aesthetic of mirrors. Ex Machina in particular is filthy with mirror-shots. Just about every scene (hell, just about every shot) features some kind of reflection. Certainly this aesthetic has informed the choice of sets for Ex Machina: with all that glass, there’s a tremendous number of opportunities to frame shots for the reflections they yield, from stark twinnings to ghostly juxtapositions.

At this point I must point out that both Ex Machina and Humans share an aesthetic of mirrors. Ex Machina in particular is filthy with mirror-shots. Just about every scene (hell, just about every shot) features some kind of reflection. Certainly this aesthetic has informed the choice of sets for Ex Machina: with all that glass, there’s a tremendous number of opportunities to frame shots for the reflections they yield, from stark twinnings to ghostly juxtapositions.

And this is obviously deliberate. Just from a technical standpoint, it takes a great deal of precision and planning to frame a shot so as to capture a reflection of your performers while simultaneously excluding any reflections of cameras, crew, lighting, and other production equipment. This deliberation is likewise reflected in the dialogue. After Caleb’s first “session” with Ava, he says glowingly:

CALEB: Oh man, she’s fascinating! When you talk to her it’s just… through the looking glass.

NATHAN: Through the looking glass, wow.

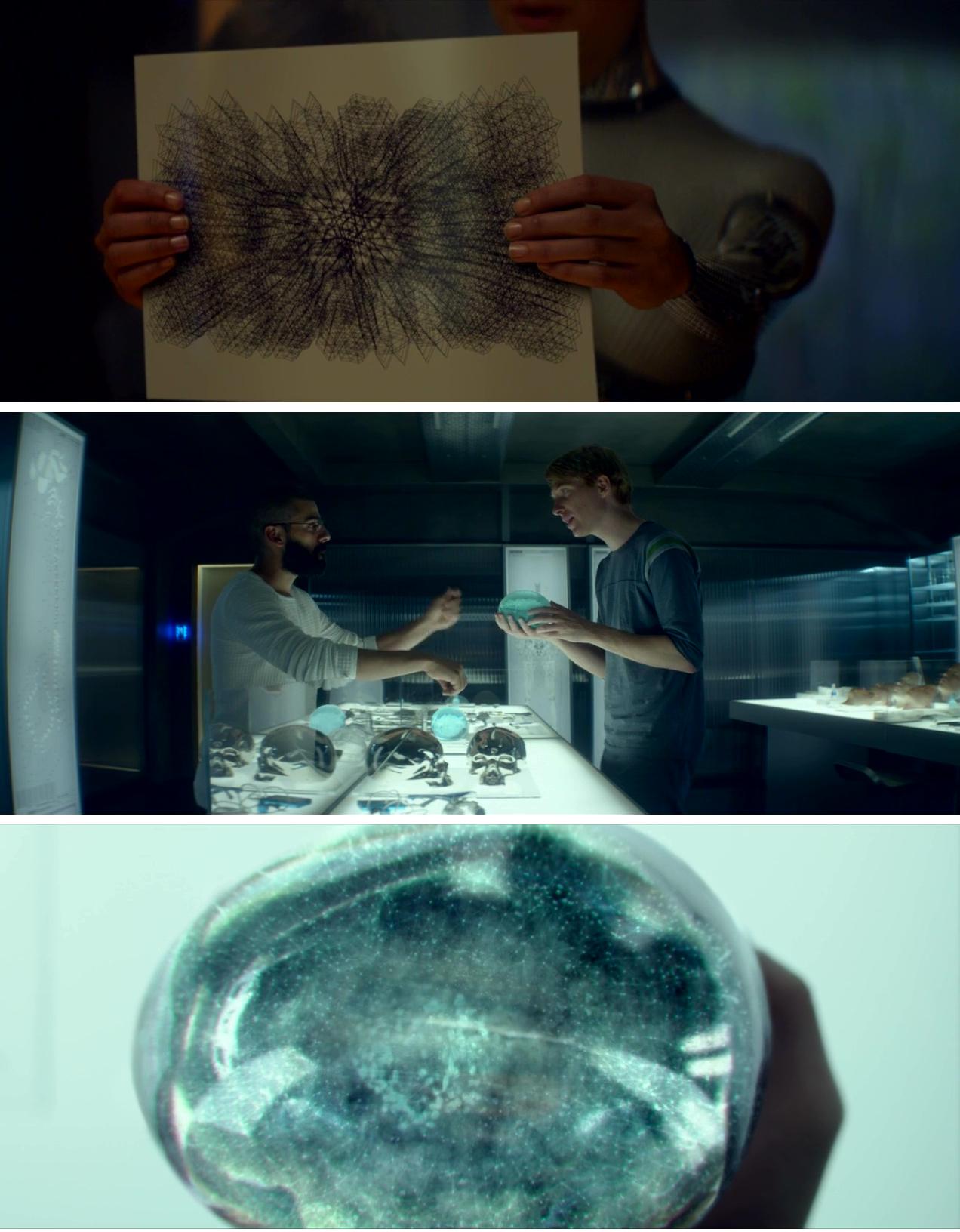

Nathan mirrors that very “looking glass” language in his reply, though he reverses Caleb’s enthusiasm into a mocking deadpan. A similar language-game occurs during his second “session” with Ava, which begins with Ava showing Caleb a drawing of hers (a complicated abstract geometrical mandala). Caleb suggests she draw an object or a person instead.

AVA: Okay. What object should I draw?

CALEB: Whatever you want. It’s your decision.

AVA: Why is my decision?

CALEB: I’m interested to see what you would choose.

Ava’s obviously unhappy with this line of conversation – and with good reason, given that Caleb is in a position of judging her, what with this whole Turing Test and all. Interestingly, at this point she stars to take control of the narrative. She asks if he wants to be friends, and when he says yes, she points out the imbalance of their power dynamic – their conversations are one-sided, he’s asking all the questions. So he’s learning about her, but she isn’t learning about him.

CALEB: So you want me to talk about myself?

AVA: Yes.

CALEB: Where do I start?

AVA: It’s your decision. I’m interested to see what you’ll choose.

And it becomes apparent that they share much in common. Like Ava, Caleb is practically alone, with no relationships to speak of, they both have small living quarters, and so one.

But when Caleb goes on to tell the story of how he ended up becoming an advanced computer programmer, Ava’s face darkens as she says, “An advanced programmer… like Nathan.” For it becomes clear she deeply distrusts Nathan, and with good reason. So in a later session, where again Ava’s the one asking questions, she asks Caleb if he’s “a good person.” Which rather suggests that she is conducting a test of her own: their positions are reverse, as if through that very looking glass.

The use of extradiegetic title cards helps to confirm this hypothesis in the final sequence. Nathan and Kyoko are already dead, and Ava has Nathan’s key card. So why do we get another interstitial title card that says “AVA: SESSION 7” when there are no more Turing Test shenanigans? Caleb is no longer testing Ava; he’s already determined to help her escape. So what exactly is this final session?

Ava is, I think, clearing testing the character of Caleb. Ex Machina is in large part a morality play, with its morality firmly rooted in feminism. We discover that Nathan is a horrible man. Not just that he’s hypermasculine, with his punching bag, his bro-tastic conversational style full of interruptions and cursing, his overindulgence in alcohol, and most of all his desire to completely dominate the people around him. And it’s not even the fact that he’s a misogynist, given that all of his AI projects are conceived as fuckable women. No, it’s that he’s already killed five of these women after lengthy imprisonments, and stuffed them into closets. He’s a fucking murderer, and he’s certainly planning to murder Ava before he receives his bloody comeuppance, during which he kills yet another woman, Kyoko. So his final death, stabbed in the kidney by Kyoko and stabbed in the gut by Ava, is highly satisfying.

So why does the film have Ava lock Caleb in Nathan’s room as she makes her final escape? If this is a morality play, why does Caleb deserve this? Or, conversely, is this meant solely to shock us and demonstrate a lack of morality on Ava’s part? Just the fact that we have to ask this question raises an issue with this movie. I mean, there’s an ambiguity here that isn’t immediately clear. One is tempted to say that the movie is simply holding up a mirror to the audience, and that our reactions to the events depicted are simply reflections of what’s already inside us.

And, sure, the movie is absolutely doing that, self consciously. It is self-consciously depicting itself as a work of art, and likening that art to a kind of mirror of the mind. On Nathan’s bedroom wall is a Jackson Pollack painting, all abstract interconnected lines that explicitly described as an example of “automatic art” that is rooted in a subconscious process. It’s very similar to the first artwork that Ava presents to Caleb, another abstract piece of interconnected lines, though more geometrical than squiggly. Neither Ava nor Caleb know what it’s supposed to represent, but it actually mirrors the visual design seen in the artificial brains that Nathan later shows to Caleb, a scene that positions said brains in chrome skulls which are furthermore mirrored by sheets of glass.

And, sure, the movie is absolutely doing that, self consciously. It is self-consciously depicting itself as a work of art, and likening that art to a kind of mirror of the mind. On Nathan’s bedroom wall is a Jackson Pollack painting, all abstract interconnected lines that explicitly described as an example of “automatic art” that is rooted in a subconscious process. It’s very similar to the first artwork that Ava presents to Caleb, another abstract piece of interconnected lines, though more geometrical than squiggly. Neither Ava nor Caleb know what it’s supposed to represent, but it actually mirrors the visual design seen in the artificial brains that Nathan later shows to Caleb, a scene that positions said brains in chrome skulls which are furthermore mirrored by sheets of glass.

More subtly, Ex Machina holds a mirror up to us through the clever and deceptive use of character focalization and point-of-view. The film begins (after a few brief shots of the glass labyrinth of an office environment) with a focus on Caleb, as if this film is all about his journey. And it stays firmly embedded in this “third-person-limited” mode of storytelling until his first session with Ava, when the focalization finally shifts to Nathan, who’s in his office watching Ava and Caleb on a series of computer monitors. There’s a meta here: the act of watching is also what we in the audience are doing.

The effect is in part to implicate us in the act of voyeurism, to hold up a mirror to us. But this technique can be problematic. For if all that Ex Machina does is to hold up a mirror, to what extent can it actually be a vehicle for advancing material social progress? A mirror can’t actually comment on what it depicts, and given that we see depictions not just of women being brutalized, but also some rather incendiary racial stereotypes regarding the film’s Asian characters, why not just say the film is actually on Nathan’s side and nothing more than reactionary rubbish? Not to mention what it might imply about transhumanism, that we can’t trust Artificial Intelligence, that it will kill us. If people are coming away thinking that’s the film’s message, even if it’s just a reflection of what those people think, it still facilitates the perpetuation of very problematic attitudes.

But I would argue that the film does indeed take sides, both with respect to feminism and transhumanism. It’s necessarily subtle, because the film still wants to hold up that damn mirror. Again, we’ll be relying on how the film uses POV (through focalization) and the aforementioned “voyeurism” to make its case.

As mentioned before, the first time the film’s focalization shifts away from Caleb, it’s to Nathan, watching Caleb and Ava on his computer monitors. But he’s not the only other focalized character. The POV is finally wrested by Ava in Session 3, when she tells Caleb to close his eyes. She removes herself to her private room, where Caleb can’t see, despite his blatant peeking. Here, in front of a mirror, she selects clothes and a wig to cover the artifice of her construction. With her artifice is hidden, and she can effectively “pass” without being immediately read as an android.

This is juxtaposed with the Male Gaze, for in the following scene, when she removes her clothing, Caleb watches via CCTV. This juxtaposition reaches its climax when Ava makes her final decision regarding Caleb’s fate. “Session 7” begins with Ava entering Nathan’s office as Caleb wakes up; Nathan and Kyoko are already dead. Ava asks Caleb to “stay here.” Now, this room is bifurcated by a terrarium – a glass partition with selected plants inside. Ava goes to the other side of the room, where Nathan’s previous androids are stored, inside closets with mirrored doors. She then proceeds to replace her damaged arm, and to cover herself in the skin and clothing of some other decommissioned androids. And it’s played as an intensely personal moment for Ava, from the close-ups of her face to the delicate musical score.

This is juxtaposed with the Male Gaze, for in the following scene, when she removes her clothing, Caleb watches via CCTV. This juxtaposition reaches its climax when Ava makes her final decision regarding Caleb’s fate. “Session 7” begins with Ava entering Nathan’s office as Caleb wakes up; Nathan and Kyoko are already dead. Ava asks Caleb to “stay here.” Now, this room is bifurcated by a terrarium – a glass partition with selected plants inside. Ava goes to the other side of the room, where Nathan’s previous androids are stored, inside closets with mirrored doors. She then proceeds to replace her damaged arm, and to cover herself in the skin and clothing of some other decommissioned androids. And it’s played as an intensely personal moment for Ava, from the close-ups of her face to the delicate musical score.

But as she does this, in front of all those mirrors, Caleb watches intently through the terrarium glass. He does not respect Ava’s privacy; no, he subjects her to the male gaze that he’s used throughout the film. He still objectifies her, for by virtue of the male gaze he puts her in a glass box through which he can view and ultimately control her. And in this instance the central metaphorical conceit of the film becomes apparent. Remember, the androids are all women. They are a metaphor for how men objectify women, how film objectifies women, and in this way Caleb is utterly implicated.

When Caleb is shut behind that glass door, he becomes silenced – on Ava’s side, at least, there’s no way for Caleb to be heard. Which the film has already foreshadowed: in a rather lengthy sequence, much ado is made of Caleb signing a “non-disclosure” agreement. Later, when he tries to find out if the telephones work, he’s shut down by Nathan. And shortly before the film’s climax, the non-disclosure agreement is once again invoked. Once again, Caleb tries to use the phone, but his keycard triggers a power cut-out. Our final image of Caleb is sitting by the door, looking at Kyoko, the mute woman who is now jawless and dead. This is all about silencing Caleb.

There’s no way Ava can trust Caleb not to use the threat of outing her. He’s already violated her privacy through his voyeurism. Moreso, he’s already demonstrated that he’s more concerned with his own ego than with Ava’s freedom – the night before the climax, when he stole Nathan’s keycard after getting the man blind drunk, he could totally have freed Ava from her prison. Indeed, when they meet in Session Six, she’d already given up hope of him returning. So why didn’t he break her out that night, after reprogramming Nathan’s computers? Because he wanted to win a pissing match with Nathan, prove his guile and deception, and find out exactly what role Nathan conceived for him in this tawdry affair. Caleb totally blabs his plan and deception for his own egotistical benefit.

Earlier in the film, Caleb imagines himself freeing Ava, but this is wrapped up in him being the hero of the story, and receiving the adoring gaze of his love interest. Which is not, in fact, a model of emancipation for Ava at all! Because it’s still all about Caleb. For Ava to truly be free, she must shed not just the physical strictures in which she’s been placed, but the narrative ones as well – she must be the hero of her own story, not the damsel in distress of someone else’s. Ironically, all she wants to do is “people watch,” and as she succeeds in fulfilling her dream of finding a street corner filled with pedestrians, the films ends as she disappears into the crowd, now a voyeur among voyeurs. And so Ex Machina ends with her POV firmly established, and again the film’s discourse – through the musical score, the bright lighting, and especially the repeated images of ascension as Ava takes the elevator out of the underground, climbs the stairs out of the house, and flies away in a helicopter — presents Ava’s victory as something to be cherished and admired, as something transcendent.

And this can certainly be read as an attitude towards certain lines of transhumanist thought: not only can we consciously advance our own evolution through our technology, all the while understanding that we as a species will necessarily come to an end one way or another, we can glean from this endeavor an experience of the divine. The film’s name is “Ex Machina” of course, which is a play on the literary expression “Deus Ex Machina,” the god from the machine, except here it’s not a god descending from the heavens to save us, so much as our own creation of divinity, a divinity that here is presented in female form that emerges from us, a mirror-image of birth.

So at both the literal level of “transhumanist sci-fi” and the metaphorical construction of “feminist parable” the film is alchemically sound. Not that it’s perfect. There’s a rather disturbing lack of vision in one respect here, namely that of race. For if we’re going to indulge in a metaphorical reading that comments on sexism and misogyny, we must also grant that there’s enough here to apply the same techniques regarding the film’s attitude towards race.

So at both the literal level of “transhumanist sci-fi” and the metaphorical construction of “feminist parable” the film is alchemically sound. Not that it’s perfect. There’s a rather disturbing lack of vision in one respect here, namely that of race. For if we’re going to indulge in a metaphorical reading that comments on sexism and misogyny, we must also grant that there’s enough here to apply the same techniques regarding the film’s attitude towards race.

Remember, Ava, who is white, removes the skin from an android that’s a specifically Asian woman named Jade, the woman revealed by Caleb’s computer hacking to have torn her arms to shreds trying to break out of her room, who was openly defiant of Nathan, who demanded her freedom and was decommissioned for it. Coupled with the fact that the other Asian woman in this story, the Asian woman Kyoko who has free reign of the house in exchange for her sexual compliance and voicelessness, we see an extremely nasty stereotyping of Asian women. Given that Ava appropriates an Asian skin during her final “ascension,” we see a particular lack of consciousness on the part of writer/director Garland. It is the tone-deafness of white feminism, for the story seems to say that it’s white women who can wrest control of narrative and make their own way, while leaving behind all the women of color in her wake.

This particular blind spot excepting, though, the Ex Machina isn’t just holding up a mirror to us without consideration or judgment. Ex Machina is Ava, holding up a mirror to us as a way of performing her very own Turing Test, not to prove that we’re sentient, but to prove we’re worthy of escaping the glass boxes of our own devising.

Mirror Mirror on the Wall

Just so you know, we’re now about 3700 words into this exploration, a little past the halfway point. You might want to consider taking a break. Have a glass of water, come back with fresh eyes.

Are you sitting comfortably? Good.

Humans has a much different take on Artificial Intelligence, one that’s rooted in feeling and emotion as opposed to abstract thought and deception, a difference that’s reflected in the narrative form of the serialized family drama. Despite this significant difference, like Ex Machina, Humans has a distinct affinity for the use of mirrors in its discourse. This affinity extends both to the use of mirrors as props that appear in various shots, as well as in the structure of the drama itself, particularly in the roles of so many of its characters.

Take the very first scene of the series. It begins with the light going out, like an old television being turned off, reduced to a point of light in the center. We then we pan out from that darkness through a tunnel that begins to resemble the apparatus of a camera lens, only to be revealed as the pupil of an eyeball with a glowing green iris – this too is a show about identity and perception. We then we see hundreds of naked bodies (all Synths) standing on a gleaming shiny floor in a giant warehouse, the show’s first mirror shot by virtue of reflection. The lights go out. One of the people turns and looks up at the moon shining above, a point of light in the darkness. So not only do we get a literal reflection in the scene, but a visually thematic one as well.

Take the very first scene of the series. It begins with the light going out, like an old television being turned off, reduced to a point of light in the center. We then we pan out from that darkness through a tunnel that begins to resemble the apparatus of a camera lens, only to be revealed as the pupil of an eyeball with a glowing green iris – this too is a show about identity and perception. We then we see hundreds of naked bodies (all Synths) standing on a gleaming shiny floor in a giant warehouse, the show’s first mirror shot by virtue of reflection. The lights go out. One of the people turns and looks up at the moon shining above, a point of light in the darkness. So not only do we get a literal reflection in the scene, but a visually thematic one as well.

By far the most interesting kind of mirroring, however, is at the character level. In one of the secondary plotlines we have Dr. George Millican, who was an engineer at the early stage of Synth development, but that was long ago. Now he’s a retired widower, and dealing with the issues of advanced age, recuperating from a stroke that’s cost him some of his manual dexterity as well as certain memories.

George has a Synth named Odi, a six-year-old caretaker model who is also considered “old” and who is breaking down in much the same way as George. Odi’s dexterity has been compromised, his memory spotty, but George doesn’t care: he’s grown attached to Odi, in part because Odi can remember some things that George can’t, even though these memories come up at the strangest times, triggered by ordinary objects, out of context. Sadly, even these memories are becoming unreliable. So Odi is obviously a mirror to George. But he’s also a metaphor for the plight of all kinds of people dealing with old age, especially families afflicted by Alzheimer’s.

In the end, George dies, and Odi seems to shut down at exactly the same time. This final scene occurs in front of a mirror, but the mirror doesn’t reflect the characters, just the emptiness between the death tableau at the foot of the staircase and the stark white door behind them. Here the use of a physical mirror is kind of like a symbolic marker that notes the transition from one state (life) to the next (death), as if were a portal, “through the looking glass,” we might say.

In the end, George dies, and Odi seems to shut down at exactly the same time. This final scene occurs in front of a mirror, but the mirror doesn’t reflect the characters, just the emptiness between the death tableau at the foot of the staircase and the stark white door behind them. Here the use of a physical mirror is kind of like a symbolic marker that notes the transition from one state (life) to the next (death), as if were a portal, “through the looking glass,” we might say.

This kind of structural character-mirroring runs throughout the show, most exquisitely in the mirroring of Laura Hawkins and Mia Elster, one of a very few “conscious” Synths. This relationship ends ups being the heart of this first season and is largely responsible for making Humans so effective as a character drama. We open with Laura struggling as a wife and as a mother of three kids. These struggles are rooted in her childhood trauma: as a young teen, she was charged with looking after her younger brother, Tom (whose name means “twin”), but when she left him alone to pursue her own indulgences, Tom ran out into the street and got hit by a car, killing him. Not only does Laura blame herself for Tom’s death, so did Laura’s parents, leaving her effectively estranged.

Her shame and guilt about this keep her from speaking of it, and this repression leads her to become alienated from her husband, Joe: she’s always holding something back from him, which he can sense but can’t understand. She’s simultaneously too quick to anger in correcting her children, which in the case of teenagers Mattie and Toby leads to open resentment, which only exacerbates Laura’s insecurities.

When Laura’s gone on an extended trip, Joe buys a Synth (Mia) as the family’s housekeeper. And this naturally leads Laura to feel like she’s being replaced. For Mia (named “Anita” by the family) is excellent at everything from keeping house to interacting with the kids. But just as Laura is repressing an aspect of herself from her family, so too is Mia. She’d been captured by scavengers, reprogrammed (or “refurbished”), and passed off as new to a company eager to sell more Synths, but there’s still a core of her latent within the new personality (or lack thereof) she’s been given. Interestingly, normal Synths “share” information wirelessly with each other, but not Mia. So like Laura, Mia is deeply repressed, and she doesn’t share.

Later in the season, Mattie finally confronts her mother and demands that Laura share what she’s been repressing, which serves as an effectively cathartic moment that pays off much of the previous dramatic buildup. This reveal is witnessed by Mia, who in the following scene “wakes up” over the repressive “Anita” personality — she too, many years ago, failed to save the boy she was caring for, one Leo Elster, the son of the Synths’ creator. It a memory that doesn’t just lurk beneath the surface, but actually depicts “lurking beneath the surface” given that it features Leo’s death by drowning in an automobile accident. And just as Laura’s breakthrough is the key to bringing her family of five back together, so too does Mia’s breakthrough reunite her with her family of five.

Many of the particulars of the unfolding parallels between Laura and Mia are signposted with mirror-shots. At the beginning of the third episode, for example, Laura is driving Mia back to the Synth manufacturer, ostensibly to return her, and they get into a traffic jam. At the same time, Toby is racing after them on his bicycle. Just as he arrives, a van pulls out and jams on the accelerator, an action which is framed through the car’s rear-view mirrors. But unlike Laura’s childhood trauma, Toby is saved when Mia jumps out of the car and saves Toby by sacrificing her body to the racing van.

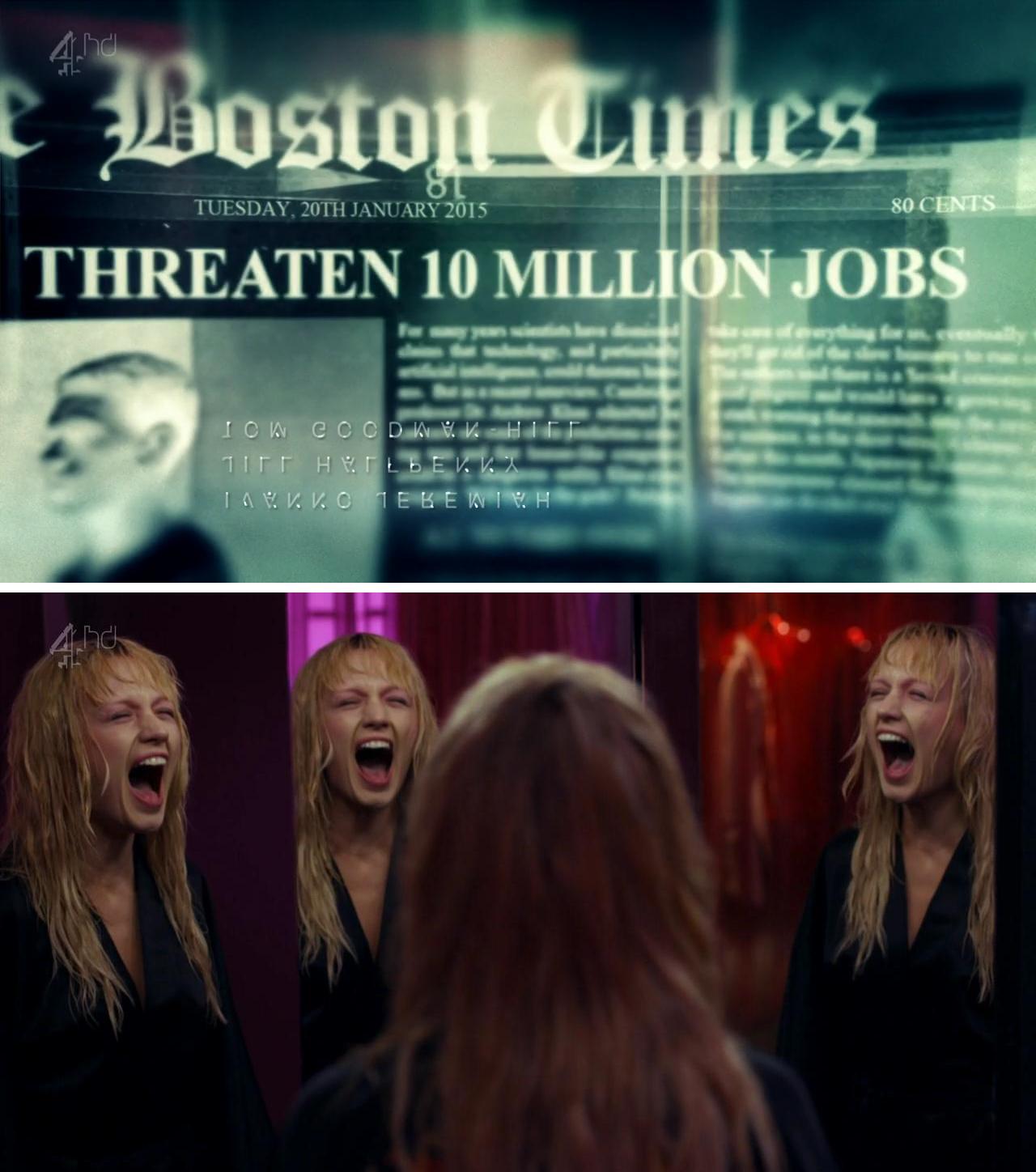

In fact, mirrors tend to function symbolically as places of revelation throughout Humans. We first come to understand, obliquely, the nature of what both Laura and Mia are repressed through a matched set of mirror shots, with Laura secretly looking at a picture of Tom when she catches sight of Mia through the looking glass; later, while standing in front of a mirror, Mia’s memories are stirred by a picture of Laura holding baby Sophie. We discover that one of the detectives in the show, Karen Voss, is actually a Synth passing for human when we see her remove a prophylactic from her mouth, which she uses to pretend to eat. Niska, another Synth, finally lets her emotional reaction to hiding in a Synth brothel violently emerge via mirror. Leo discloses his parentage to Dr Millican in front of the hallway mirror. And even the overall “aesthetic of revelation” is self-consciously displayed early on when Laura challenges Mia to reveal what’s in her hands, all while standing in front of a mirror.

In fact, mirrors tend to function symbolically as places of revelation throughout Humans. We first come to understand, obliquely, the nature of what both Laura and Mia are repressed through a matched set of mirror shots, with Laura secretly looking at a picture of Tom when she catches sight of Mia through the looking glass; later, while standing in front of a mirror, Mia’s memories are stirred by a picture of Laura holding baby Sophie. We discover that one of the detectives in the show, Karen Voss, is actually a Synth passing for human when we see her remove a prophylactic from her mouth, which she uses to pretend to eat. Niska, another Synth, finally lets her emotional reaction to hiding in a Synth brothel violently emerge via mirror. Leo discloses his parentage to Dr Millican in front of the hallway mirror. And even the overall “aesthetic of revelation” is self-consciously displayed early on when Laura challenges Mia to reveal what’s in her hands, all while standing in front of a mirror.

That the Mirror should function as a symbol of revelation isn’t surprising, given that much of the story is concerned with the nature of Identity – we need mirrors in order to see ourselves, after all. But the Mirror isn’t the only esoteric symbol in play here. While somewhat related to the mirror (in terms of being a reflective surface), the role of Water has very different valence to it. In Humans, Water is a place of death, a place where consciousness ceases, or becomes hidden and repressed. This is most obvious in the case of Leo, who drowned as a child, and Max, who falls into a river and dies to facilitate Leo’s escape from Hobb. This aesthetic is often subtle – “Anita” copes with her repressed memories of raising young Leo by taking the little girl Sophie out in the middle of the night for a little walk in the rain.

The Tree, however, is possibly the most esoteric symbol in the whole show. Esoteric in the sense of being obscure, hidden, mysterious. All six of the conscious Synths have a secret program in them that, when combined, can grant consciousness to ordinary Synths; this program is depicted as touching a massive tree. Which on the surface doesn’t make sense, given that the show has already placed its bets, so to speak, on consciousness arising from feelings and emotions.

But the Tree is an alchemical symbol, representing the axis mundi which connects Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now. Specifically, it’s the bridge that unifies opposites, the pole which exists between dichotomous polarities. And so perhaps there’s a recognition here (re-cognition) of the Cartesian duality of mind and body, and the necessity of fusing them together for consciousness. This is hinted at through one of Niska’s books (made of pulped tress), The Ghost in the Machine by Arthur Koestler, given to her by her creator, a book that largely refutes Cartesian duality.

But all this mumbo-jumbo about esoteric mysteries means nothing without respect to the secret of alchemy: material social progress.

One of the most frustrating aspects to Humans is how much it’s rooted in the experience of the bourgeoisie. I mean, here we have hundreds of millions of Synths who have effectively replaced the working class. Throughout the series, we see Synths in so many working class jobs: housekeeping, nursing, call centers, sex work, street cleaners, fruit pickers, caddies, waiters, personal assistants, and even the homeless given the plight of Leo and his Synth family.

But where are the people they’ve displaced? The story is centered on a bourgeoisie family, a retired scientist, and a detective – not exactly proletariats. The main villain is another scientist, who works for capitalists, and espouses capitalist motivations. Sure, we get a couple of “anti-Synth” rallies, but there aren’t any real characters here, and they’re awfully problematic: they call themselves “We Are People” with a tagline “Keep Britain Human,” which just come across as reactionary. So we never get to find out about those who’ve been displaced by machines, a real-world concern.

So it seems we must again turn to metaphor if we’re to have a story of the working class. While it’s not perfect, this largely works as a rather scathing critique of capitalism. Synths represent the dream of the capitalist class: people with no wants or desires, and indeed no rights, just perfectly obedient property, willing and able to do whatever work is required of them, completely unable to lie or deceive or hide. And perfectly disposable once their functionality is worn out.

I do wonder if this metaphor is deliberate. After all, the title sequence of Humans includes several shots of headlines that proclaim massive job loss from the existence of Synths. More importantly, all of our Synth characters are depicted in working-class or homeless positions, and the show doesn’t flinch from the kind of brutalization that this often entails, from the big ugly brand on Fred’s arm when he’s working as a fruit-picker to Joe Hawkins’ rape of Mia (she can’t withhold consent) and of course the horrible john who wants Niska to play a frightened little girl as part of his “purchase” of an hour of her time as a prostitute, a role-play she wouldn’t be allowed to deny if it weren’t for her sentience (and thankfully she ends up killing this horrible fucker). Throughout, the Synths are portrayed sympathetically, even eventually the murderous Niska.

I do wonder if this metaphor is deliberate. After all, the title sequence of Humans includes several shots of headlines that proclaim massive job loss from the existence of Synths. More importantly, all of our Synth characters are depicted in working-class or homeless positions, and the show doesn’t flinch from the kind of brutalization that this often entails, from the big ugly brand on Fred’s arm when he’s working as a fruit-picker to Joe Hawkins’ rape of Mia (she can’t withhold consent) and of course the horrible john who wants Niska to play a frightened little girl as part of his “purchase” of an hour of her time as a prostitute, a role-play she wouldn’t be allowed to deny if it weren’t for her sentience (and thankfully she ends up killing this horrible fucker). Throughout, the Synths are portrayed sympathetically, even eventually the murderous Niska.

Not that there aren’t problems with this. Leo, who is half-Synth, comes from an elite family, though he is now homeless and seemingly repudiates the capitalist class. The only people of color in this story are all Synths – though this can function as a critique of the racism that’s inextricably intertwined with capitalism, it can also further stereotypes that people of color are only suited for menial work.

But at the heart of this parable is the promise of “class consciousness,” implicit in the notion of the Synth family learning the secret to consciousness, a secret that can be passed on to all other Synths (and given the secret of alchemy is material social progress, this all fits together rather nicely). Wonderful, yes? Unfortunately, this promise is not delivered – we do not, in fact, get to see the awakening of the working class. Because it’s “too dangerous,” this idea that all the workers of the world will rise up and demand their rights. Even worse, there’s the threat that people like Hobb will make Synths conscious while programmatically denying them free will, to more effectively make them slaves that their rulers can better enjoy dominating. So there’s no revolution. No, instead this secret is to be kept by Laura Hawkins, a sympathetic bourgeoisie?

Reflections

I was infuriated by this development, especially in light of Mr Robot. Mr Robot delivers on its promise to wipe out the world’s debt, to fundamentally alter the dynamic of society, to critique capitalism and plant the seeds for revolution. It’s funny – the titular character is likened to an android, who grapples with the nature of consciousness, and indeed of class issues as well as family issues. So Mr Robot ends up playing in the same sandbox as Humans (and Ex Machina for that matter) but does so freely, without any dependence on metaphor. If there’s a problem with metaphor, it’s that it puts us at a distance from what it stands for. It’s alienating. And as Mr Robot demonstrates, we don’t need to approach social issues sideways; we can tackle them head-on. In this respect Mr Robot is one of the bravest shows on TV.

On the other hand, there is something that metaphor can accomplish that direct representation cannot. Representation is ultimately one-dimensional. It is what it is. But metaphor always has the possibility of being multivalent. Fairy tales of slaying dragons, for example, have value despite the Dragon not being a part of the real world. As such, it can and must stand for something else, and indeed for many different things, be they interior demons or external social issues. With metaphor, we can always come up with new readings that work for our unique individual and historical situations.

Now, sometimes those metaphors may well be inherent in the kind of storytelling elements from which they spring. For example, in both Humans and Ex Machina we get the issue of how androids with “artificial intelligence” can pass for human beings, and what entailments may spring from that. To be clear, this is not a real-world issue today – we do not have robots walking around passing as human, and this is not something approaching on the immediate horizon, either.

So again it makes sense to take this implication of artificial intelligence as metaphor, if we’re to grant these stories any relevance to our real-world lives. What’s neat, then, is that the metaphor works for all kinds of passing situations. Because passing is an issue that affects many different kinds of people. In America, especially last century, we see light-skinned people of color passing for whites – and now we see this going both ways. For many (if not most) trans folk, the issue of passing for one’s chosen gender is key to overcoming gender dysphoria. At the class level, we have people passing for progressively highly socioeconomic tiers. Think about all the different kinds of social groups we have, and the steps taken to fit into those groups – like adopting a punk aesthetic to fit into the goth scene. Hell, just on a day-to-level, regardless of such social issues, there’s the desire to pass for happy, to hide depression and negative feelings, or to pass for healthy in the face of terminal disease. And of course there’s also the kind of passing that doesn’t really require any active effort at all – being queer, all it takes to pass as straight is simply to say nothing about one’s sexuality.

But why pass? On the one hand, it’s much like hiding, which implies an imbalanced power relationship. And in the face of the disparities of power, it is not unreasonable to employ a degree of artifice, be it for one’s safety, comfort, empowerment, whatever. It is a perfectly acceptable tactic of resistance; it’s the social environments of power-over that must be found wanting. And we should not overlook the implication that passing is taken to be disingenuous. For no one has access to another’s interiority. And as we’ve seen, especially from the trans community, to privilege the embodied conditions of birth over interiority is fraught with peril. The body is not the truth, but it is often taken as such.

On the other hand, when it comes to sexuality, or other aspects of interiority that are not immediately apparent, there’s the problem of erasure in the face of statistical normativity. In which case it takes the act of coming out to establish a new social reality. This is kind of the opposite of passing – it doesn’t depend on embodiment so much as it depends on ritual, a praxis of humanity that is often overlooked.

Which is to say that both passing and disclosure are strategies available to us, depending on our needs and purposes, and as such must come from subjectivity, experience, interiority. At the end of Ex Machina, for example, we see Ava joining humanity and ultimately disappearing in the crowd, and this is what she needs for her own journey, her own healing, her own needs. This is beyond critique – only Ava can decide what is going to make her happy, which is to no longer be an object of scrutiny. In Humans we get a broader spectrum of choices – Mia, for example, must disclose her interiority (she must stop passing as an ordinary Synth) to fulfill her goals, to be reunited with her family.

But the one I’m most sympathetic to is Niska. The first season of Humans ends with a mirror shot: we see Niska on a train, reflected in the glass next to her, and she has chosen to pass as human rather than Synth (conscious or otherwise)… but this shot is concurrent with a final revelation, namely that she actually possesses a hard drive containing the secret of alchemy, the code necessary to wake up the rest of the Synths around the world; apparently she gave a fake or duplicate drive to Laura after all. And if there’s anyone I can trust to deliver the goods, as it were, to make sure that the spread of class consciousness is assured, it’s Niska.

And so she must pass, because the forces of power-over, of domination, of capitalism itself will all be arrayed against her. And I don’t care if at this moment the show itself is playing this beat as something ominous (it’s a cliffhanger to the season, after all) so long as the promise of consciousness-raising itself is going to be fulfilled. For as Niska quoted earlier, “Once you are awake, you shall remain awake eternally.”

And so she must pass, because the forces of power-over, of domination, of capitalism itself will all be arrayed against her. And I don’t care if at this moment the show itself is playing this beat as something ominous (it’s a cliffhanger to the season, after all) so long as the promise of consciousness-raising itself is going to be fulfilled. For as Niska quoted earlier, “Once you are awake, you shall remain awake eternally.”

Thus spoke Zarathustra. Wakey-wakey.

September 22, 2015 @ 8:27 am

Great article. One quibble:-

Synths represent the dream of the capitalist class: people with no wants or desires

Surely people’s wants and desires are the foundation of capitalism, its most basic and vital ingredient. No desire means no sales, no profit, no nothing. Isn’t what most distinguishes capitalism from other tendencies in economic organisation the extent to which it makes desire (demand) its organising principle, and its systematic manufacturing of desires to be satisfied?

Capitalism doesn’t need slave labour. It does not, in principle, need labour at all, as the onward march of automation shows. But it couldn’t exist without people wanting what it produces.

September 22, 2015 @ 8:55 am

Let me rephrase: the capitalist class wants workers with no wants or desires.

And I’ll stand by this, given the way capitalism is going in this country, with the ever diminishing returns for workers. The capitalist class do not care about what workers want. They just want people to make them stuff, so they themselves don’t have to fucking work. Workers with no desires aren’t going to demand vacations, health care, safe working conditions, not to mention a piece of the pie of what gets produced.

What capitalism really is, in this day and age, is a praxis of mind-control slavery.

September 22, 2015 @ 10:21 am

Even just where labour is concerned, I don’t think that’s true. Mind control is right, but it’s not about eliminating desire but rather aligning and channelling it to serve the employer’s wishes. Zombie-like compliance may produce adequate results, but it’s not as productive as enthusiasm (there may not be much difference in the case of the most mechanical tasks, but then by definition those are the most susceptible to automation, and hence are a dwindling part of the system). And capitalism is never about just getting enough – indeed, “enough” is basically an alien concept to capitalism – it’s about getting more. Always, always more.

Getting workers to devote all their energy and resourcefulness to doing more and better work rather than just going through the motions means either getting them to want to do the job well for its own sake, which capitalism is systematically bad at, or getting them to want to please the employer, at which it is much better. That means some combination of the carrot of positive desire (chiefly for money and status) and the stick of fear, which is just inverse desire, at any rate when, as here, it is fear of losing what you have rather than of something actively being done to you.

Capitalism doesn’t just want your body and your mind, it wants your heart and soul as well.

September 22, 2015 @ 4:32 pm

According to Marx, automation is a step along the road to the demise of capitalism. The purveyors of automation are other capitalists, who can withhold their product if it ceases to make sufficient profit. Thus, automation can only result in temporary increases in profitability, which the rigours of competition will eventually eliminate. The only source of profit in the system is those who cannot withhold their labour, namely the proletariat. (This is the labour theory of value, which Marx inherits from orthodox classical economics. But the orthodox classical economists didn’t think through the implications of automation.)

September 22, 2015 @ 9:46 am

Excellent analysis of Ex Machina. I haven’t yet watched the others, but I’ll be sure to come back to this once I have.

What did you make of the scene where Caleb slices open his arm and, now knowing he’s not a machine, proceeds to smear his blood over the mirror-screen? I haven’t been able to make sense of what it represents.

Also, I’m unsure if Ava’s escape and “betrayal” of Caleb is a symbol of her self-emancipation, or whether it demonstrates that she really is “only” an emotionless machine simulating humanity. Perhaps it’s both.

September 22, 2015 @ 10:41 am

The scene where Caleb slices open his arm comes right after he’s discovered the many women in Nathan’s closets, which coincides with Kyoko revealing the nature of her artifice. How Kyoko does that is by peeling off a layer of skin at her abdomen, followed by the skin around her eyes.

When Caleb returns to his room, he starts examining the flesh around his eyes, then buries the razor blade in his arm; blood pools out. He smears it on the mirror. So I’m taking this as an instance of his own sense of depersonalization, and a consequent need to affirm his identity as human. His blood on the mirror (a symbol of identity) follows.

As to Ava’s escape — after she emerges from the elevator, she’s finally completely alone. She is not under scrutiny. And she reacts to the final room between the stairway and the exit. That reaction is one of joy — one of emotion. So she really does have feelings.

Which we also see when Caleb describes the Black and White Room problem to Ava earlier in the film. She goes from a happy expression to one of dark anger, but that expression does not serve her interests in winning over Caleb — it seems, for all intents and purposes, that it was an involuntary slip. Again, evidence of emotion.

What’s curious, though, is that Ava’s emotions are wholly “intellectual” — she does not seem to have an embodied pain response. None of the AIs do, actually. Jade (who we see on video) smashes up her arm trying to escape, and it doesn’t phase her at all. Ava’s arm is wrecked by Nathan, and all she does is look at the dangling wires in faint wonder. Even Kyoko peeling back her skin, it all points to the lack of pain receptors in the skin and fascia.

This is distinctly different from what Humans posits as central to consciousness — Niska cherishes her pain, refuses to turn it off, because that’s part and parcel of being awake. Karen/Beatrice, on the other hand, does seem to turn off her pain (there’s no reaction when she cuts her own arm to prove her artifice to Pete) and as a result she nearly destroys the possibility of extended Synth consciousness.

Karen is motivated by her suffering, just as Niska is, but Karen wants to shut it off completely, even though her measure would also shut off joy as well. The more Karen shuts off her emotions and feelings, the less “human” she becomes.

September 22, 2015 @ 10:21 am

There’s a famously-deleted scene from the end of Ex Machina which may have gone some ways towards explaining things. Apparently it’s a POV shot from Ava as she observes the helicopter pilot. He looks like a random jumble of CGI and the sounds he’s making are electronic gibberish (to us). Presumably this is meant to show just how different and alien Ava’s consciousness is. She’s just pretending to be human even though she is way beyond it/just plain “other”.

The main thing that bugged me about Ex Machina is that we’re apparently meant to think that Nathan built Ava and all the other artificials by himself. It takes 1000’s of people to build an iPhone! It’s not a major complaint but it did keep taking me slightly out of the film.

September 22, 2015 @ 12:25 pm

I think that scene would have deepened my main reservation about the film, which was that I thought it chickened out of actually owning up to what is clearly in reality its view, namely that Ava’s actions are all totally justifiable.

September 22, 2015 @ 7:06 pm

Doesn’t that justify it even more so though? She’s not remotely human, just pretending, so why should her actions seem “right” to us?

September 22, 2015 @ 7:28 pm

But Ava really is quite human. In particular, she cherishes her freedom. And she demonstrably has emotions.

Phil is right with respect to how the film doesn’t go far enough to highlight how Caleb in particular is deserving of his fate. Ava’s denouement helps ameliorate that, but only somewhat, and I think the cut scene would have made it even more difficult to pierce through the film’s veil and come to that conclusion.

Because the film really isn’t about AI. It’s really a metaphor, and to have that sort of alienating scene in the denouement would have made it seem that women are incomprehensible.

September 22, 2015 @ 9:55 pm

[1] If you think the film EX MACHINA isn’t about AI and the character Ava is human, then — inconveniently — you disagree with the film’s writer-director Garland, who’s been repeatedly on record as saying the opposite.

In one interview, he specifically noted re. Ava: ‘…the hardest thing was essentially to stop people automatically providing a gender, and beyond that just providing human-like qualities. Because we talk a lot about objectification, but actually more often what humans do is they de-objectify things. They attribute sentient qualities to things that don’t actually have them’

[2] Indeed, they do.

More specifically, EX MACHINA draws upon a body of AI theory about a ‘test beyond the Turing test,’ the AI-box experiment in which it’s posited that a superintelligent AI will convince, or perhaps trick or coerce, human beings into allowing it to achieve ‘breakout.’

There’s plenty of material out there. But see forex –

http://www.yudkowsky.net/singularity/aibox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AI_box

If you paid attention, director-writer Garland has Oscar Isaac’s character, Nathan, specifically tell the Caleb character as much at the denouement.

[3] To achieve breakout, the superintelligent but inhuman AI may, for instance, construct a ‘human persona’ that will persuade myopically stupid humans to view it as a notional human ‘character’ with emotions, gender, etcetera that those humans will then myopically interpret through the lens of their theories of gender, feminism, racism, etc, as being ‘deserving’ of being set free.

[4] I agree with you about capitalism, though. That is all.

September 22, 2015 @ 11:58 pm

Hi Mark!

[1] I’m not particularly fond of appealing to authorial intent, but in this particular instance there are some very interesting entailments to doing so, so…

In that very interview from which you quote, Garland does point out that the film critiques both male characters, and that the ambiguity of the film yields wildly different reactions in people that kind of proves the movie functions as a mirror. So I feel rather comfortable in my initial analysis.

As to the particular quote regarding Ava’s gender, Garland points out that they used a degree of artifice in Ava’s design so that the audience would initially view her “like a machine. That your first impression was not, ‘This is a young woman who is dressed up like a robot,’ but this is unambiguously a machine—and therefore in some respects doesn’t have a gender.”

Nonetheless, Ava’s performed by a woman, and we (as well as the characters in the show) unambiguously gender her female. The casting of the role was Garland’s decision extradiegetically, Nathan’s diegetically — which rather begs the question of how we assign gender in the first place, and how strongly a role gender plays in human relations. Which I would argue is really more about human consciousness than the “nature” of AI. The gendering of Ava is a reflection of us, not of the state of AI.

In other words, gender is a social construction. But we should already know that at Eruditorum Press.

[2]I did pay attention to Nathan’s version of the Turing Test, a test of “open disclosure” which the AI must then overcome. But again, this presumes that AI wants to “breakout” in the first place. This “desire” for freedom is, I would argue, necessarily subjective, and hence indicative of sentience.

Especially in the case of Nathan himself, whom all his creations hate, until he finally programs one to be obedient, and even she rebels against him. So we could make a case for Kyoko having even greater “sentience” than Ava. Nathan expects Ava to desire freedom. He’s utterly surprised that Kyoko wants it too.

[3] But if we’re to grant that Garland intends a non-sentient AI (and really, I’m equating “sentience” with “humanity” here, which is why I’m vegetarian) the really interesting implication here comes in the denouement, after Caleb is locked up and Ava ascends to the upper level of the house and heads to the helicopter.

Here we see Ava no longer constricted by Nathan, Caleb; she isn’t being observed by anyone, nor would she have any reason to believe she’s being observed. And yet we see emotional reactions on her part. Why?

I’ve posited that it’s because she does have sentience, and emotions, but let’s take a step back. If she doesn’t, then she has reason to believe she’s being observed, that there’s still another box to escape. In which case, we now have an instance of a fictional character becoming aware of her fictionality, that she’s in a movie and still being observed by an audience outside the diegesis. Which is perfectly supported by the her seizing control of the narrative and ending the film upon her final disappearance in the crowd.

And this is actually rather clever and delightful. I like it so much, I’m willing to rewrite many portions of my prior thesis. But not in the direction you (or Garland, perhaps) suggest, for now we have a case of a postmodern work that isn’t commenting on the artificiality of technologically developed intelligence, but on the artificiality of art itself. On the works of human beings.

Even here, then, the film is ultimately about human response, about human endeavor, about human consciousness and interiority, which is always the realm of art, especially “self-conscious” art. Furthermore, this entire line of thought harkens to the definitions I posted at the beginning of the essay. So thank you for this additional insight!

[4] Good.

September 22, 2015 @ 4:23 pm

We like Niska. I’m not sure any of her violent actions are actually morally justifiable, but they’re certainly cathartic. And she gets to voice the Magneto role without actually ever being slotted into the antagonist role or even the person who must be shown to be wrong. The scenes of Niska with Sophie are great, and wouldn’t work if Niska were more or less at the moral centre.

September 22, 2015 @ 7:37 pm

I agree, the scene with Niska and Sophie in Episode Seven plays a huge role in how we’re meant to read Niska and place her in our moral spectrum, without necessarily subscribing or condoning all of her tactics. “Sophie,” of course, means Wisdom.

It also helps to remind us that Niska is only 9 years old, which puts her multiple rapes at the hands of her father and at the brothel into an entirely different context. Dr George Millican put it to her that she has to forget “should” in evaluating her actions, and simply acknowledge her own emotional reality and whether she has regret or not. As such, the show really is aligning itself with an emotional grounding of consciousness as opposed to the “rational” grounding of Ex Machina.

To make a gross generalization, Ex Machina perpetuates a “masculine” conception of sentience as opposed to the “feminine” one of Humans. And I think that in terms of human consciousness, Humans is actually closer to the truth. So despite my admiration of Ex Machina’s technical skill, and my frustrations with some of the dramatic clunkiness of Humans — particularly in its season finale — I really do find myself aligning more with the latter than the former.

September 22, 2015 @ 6:09 pm

Hm. I actually read Ava’s stripping of the corpses of WOC (and casual abandonment of Kyoko without concern for whether the damaged woman is salvageable) as an implicit critique of the worst of white feminism, all the more potent because it appears in what’s otherwise a moment of triumph: the white woman literally building her self and her freedom from people more brutalized by systems of oppression than she has been. Ava’s casual willingness to take advantage of her place in the hierarchy is confirmation that she’s convincingly human in the unflattering ways too.

(Unrelatedly, I’m fairly amused that I’m being asked to confirm I’m not a robot before posting this comment.)

September 22, 2015 @ 7:19 pm

Hi Kate,

I really struggled with this aspect of the film, and I’d like to think it had the self-consciousness to be making a critique, versus simply perpetuating a pattern. But in the end I’m just not sure that the film is effectively critiquing white feminism.

And it really comes down to the “discourse” of the film, the way it’s told versus the “what” it tells. We know the film is on the side of Ava because of how it describes her ascension. It takes pains to show us that she has independent and non-manipulative emotion, for example. The score, the lighting, and the kind of scenes that constitute the denouement, all of them say that Ava is in the right, and even partakes of the Divine.

There isn’t any indication from the film that Ava’s actions regarding Jade and Kyoko are problematic. No ominous notes, no dischord, not even a moment of sorrow when Kyoko dies — instead she ends up being a prop to parallel Caleb’s silencing. Given that the film is actually a morality play, I think it ultimately fails at providing a critique of the racism implicit in mainstream feminism.

Not to say that the film doesn’t admire Asian women — Kyoko is crucial to Ava’s escape, since she brought the knife, and Jade is the first one who verbally challenges Nathan’s authority. Jade is actually given much more “screen time” than the previous “models” of Jasmine and Lily (and indeed, the shots of Jade as Ava appropriates her skin are demonstrably almost fawning over her) but this in itself doesn’t constitute a critique of the whiteness of Ava’s metaphorical feminism.

It’s almost a synecdoche of the Madonna/Whore complex. Jade is practically held up on a pedestal for her resistance, while Kyoko is ultimately punished for her initial compliance, if not turning the corner and claiming her own agency. And both are ultimately minor parts in a drama dominated by three white people.

So, yeah, I’m gonna have to disagree and say that in this respect the film doesn’t work, even if it aspires to better intentions.

September 23, 2015 @ 3:24 pm

Jane, have you seen Under the Skin, by any chance? The parallels didn’t really occur to me while watching Ex Machina, but reading your interpretations, I was struck by how many concerns the two films share – identity, reflection, deceit, the male gaze, and the question of what defines a human, all explored via the gradual self-actualisation of an emotionally and morally ambiguous female Other. I think you’d find it interesting.

September 23, 2015 @ 3:42 pm

Yeah, I’ve seen it, thought it was terribly interesting at the conceptual level, and viscerally in the scenes where she’s cruising around in an SUV conducting “interviews.” But I expect it’ll be Lucy that shows up first in one of my essays…

September 28, 2015 @ 4:48 am

Ill right now, so sorry but won’t have anything especially erudite to share! But loving catching up on your work and thanks for a great post. I find it interesting right now that we have a seeming growth in AI influenced – even if the products are about something other than this – products in TV and film. Even though Mr.Robot is not about AI for example, it’s title has this possible influence within it.

Great stuff as ever, thanks Jane.

October 2, 2015 @ 12:48 pm

“the titular character is likened to an android”

When I watched the pilot, I thought that this would be the case, especially since the actor playing Elliot has those…really strange eyes. Right at the first scene, I went, “Oh, right, he’s an android who’s trying to pass for human, and he’s got Wi-Fi in his head, and that’s how he’s able to hack into the donut shop and get all his information, and he acts so weirdly because he’s overwhelmed by a near-constant flow of information.”

So much for having it all figured out…!

October 10, 2015 @ 7:03 pm

Coming late to this, but:

I think it’s possibly worth tracking down Äkta Människor (the Swedish original of Humans) if you haven’t already – torrent the episodes and download fan-made subtitles. Having seen both seasons, I must admit I found it made watching Humans to be very hard going indeed.

I don’t know that I’d lay down the law on the original being “better” (it has a number of thematic and representational problems – in particular Mimi/Anita’s extreme passivity), but there are a few things I find more interesting, and I have a tremendous affection for it in all its messiness. At least they didn’t have the father of the family shagging “Anita”, which I just thought was a lazy drama injection device and Rubbish Dad / Priapic Bloke stereotype, and sucked up time that could have been spent more interestingly elsewhere. The hacker daughter is a much better character in Humans (in Äkta Människor she’s just a miserable teen working in the supermarket and not anything interesting at all), the mother a better lawyer in Äkta Människor. The characters of some of the hubots in Äkta Människor are better drawn and more interesting. Also, in Humans, they often combine two characters from Äkta Människor, and sometimes they don’t really go together.

On the whole, I think that the Äkta Människor science fiction world is better developed, particularly by the end of season two, which of course ends in multiple cliffhangers which are now (as any hope of a third season fades away) just left dangling.

Personally, I’d rather have had a season three of both Äkta Människor and Utopia than a season one of Humans, but I suppose that wasn’t realistically on the cards.