I Think It Would Be a Good Idea (Civilization)

In case you missed it, “The Blind All-Seeing Eye of Gamergate,” a longform piece on topics closely related to The Super Nintendo Project, went up on Saturday.

In case you missed it, “The Blind All-Seeing Eye of Gamergate,” a longform piece on topics closely related to The Super Nintendo Project, went up on Saturday.

At last, the false dichotomy between playing video games and saving western civilization stands revealed. But when we choose to do both at the same time, what exactly is the civilization that we are saving, and how might that shape our understanding of certain larger conceptual wars?

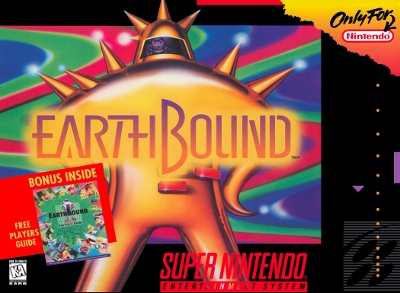

In bluntly materialist terms, which are after all the best way to approach civilization, it is another instance of a PC game getting a fundamentally middling SNES port, in the same vein as Populous and SimCity. There are no doubt those for whom this is “their” Civilization – the version of a monumental piece of video game history. This is the game that inspired Iain Banks to the phrase “outside context problem,” for fuck’s sake. Or, at least, it’s the crummy console version of the predecessor to that game. Certainly that’s where my history here intersects – somewhere past 1996 with a lot of Civ2, in a phase of video gaming otherwise defined by Diablo and Quake. High school, notably, where the Super Nintendo was late elementary school/early middle school.

The games are largely similar – Civilization II refines the original, as opposed to reworking it from the ground up. It’s more balanced and more elegant. This is doubly so when compared to the SNES port – the gap from this to 1996 is in many regards far more shocking than the gap from Donkey Kong Country 2 to Super Mario 64. But the basic thrill of the mechanism and its dizzying central metaphor persists. I compared it to Populous and SimCity earlier, and it really does manage to be a fusion of the two, combining the granular deep systems of SimCity with the cosmological scale of Populous to great effect. You may have had godlike powers in SimCity, but the scale of it was always small – one’s cities fundamentally never felt vast. Civilization feels vast easily, especially in the early stages of the game, which is as it should be. The effect of your initial tiny and contextless patch of land on which you build your capital slowly opening outwards until you encounter the Other, then borders, and finally a coherent world is genuinely effective, making the scope of what you can do feel real and substantive.

But we must be careful here. This sense of progressively illuminating an exterior world is certainly the form of western civilization as depicted here, but it is not the content. We’ve identified the story Civilization likes to tell, but not how it tells it. The answer to that question is inherited from the Avalon Hill board game Civilization is unofficially based upon: a tech tree. This is perhaps Civilization’s most significant not-quite innovation – a sublimely smooth implementation of an interlocking ladder of game upgrades that also serves to create a technologically deterministic narrative of human history from road-building to space colonies.…

se apparently it’s podcast week here at Eruditorum Press, and creating new podcast threads is more fun for me than watching Firefly again, today I’m going to introduce yet another new podcast as part of the Oi! Spaceman family. This one is called Consider the Ray Gun, and it’s ostensibly going to be about reading old science fiction books, but since it’s an Eruditorum Press thing it’ll likely go wildly off topic in an episode or two.

se apparently it’s podcast week here at Eruditorum Press, and creating new podcast threads is more fun for me than watching Firefly again, today I’m going to introduce yet another new podcast as part of the Oi! Spaceman family. This one is called Consider the Ray Gun, and it’s ostensibly going to be about reading old science fiction books, but since it’s an Eruditorum Press thing it’ll likely go wildly off topic in an episode or two.  It’s Shabcast listenin’ time again.

It’s Shabcast listenin’ time again.

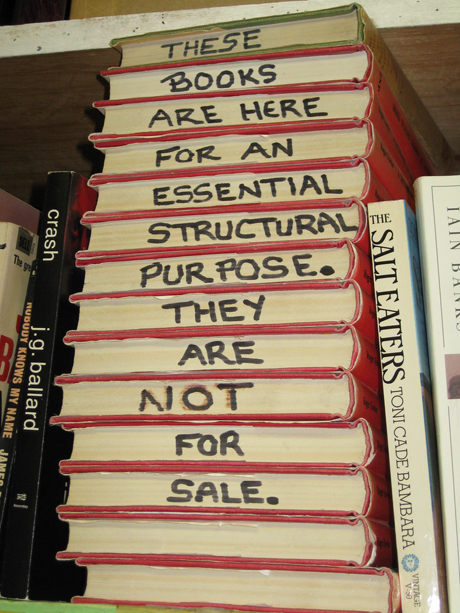

No, I’m not going down the rabbit hole writing an essay on spaghetti, myths, and donuts. It’s just a clever title to cover up the fact that I haven’t had time to write in a while as I’ve been whipping The Last War in Albion: Book One into shape, and it’s finally given up and submitted to my ministrations. It looks like it’s clocking in at 237,000 words and 210 pretty pictures, covering 760+ pages. Whew. So that should be coming out pretty damn soon.

No, I’m not going down the rabbit hole writing an essay on spaghetti, myths, and donuts. It’s just a clever title to cover up the fact that I haven’t had time to write in a while as I’ve been whipping The Last War in Albion: Book One into shape, and it’s finally given up and submitted to my ministrations. It looks like it’s clocking in at 237,000 words and 210 pretty pictures, covering 760+ pages. Whew. So that should be coming out pretty damn soon.  A Guest Post By Anna Wiggins

A Guest Post By Anna Wiggins Stories belong to all of us. Sounds like a trite, sentimental truism, doesn’t it? So let’s add a vital corollary: Because we make them.

Stories belong to all of us. Sounds like a trite, sentimental truism, doesn’t it? So let’s add a vital corollary: Because we make them.