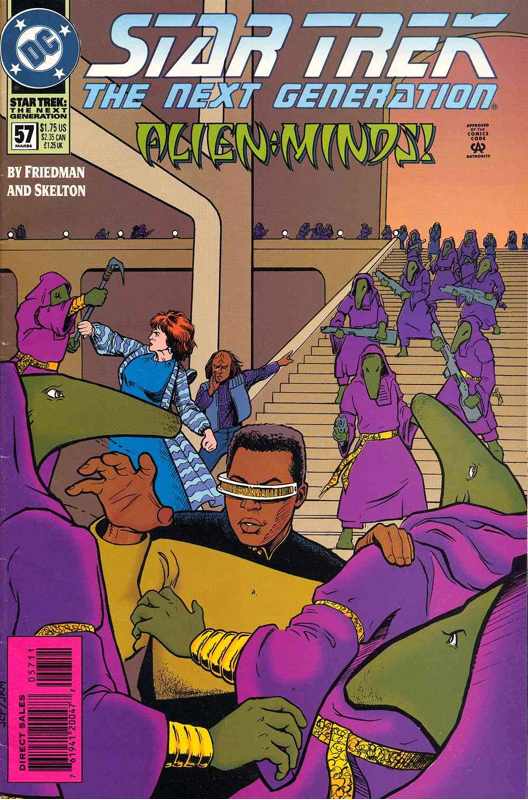

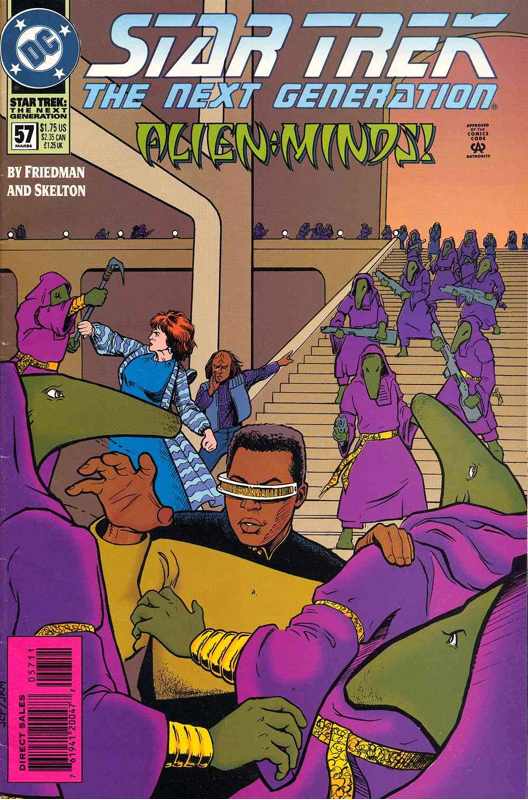

So the Ergeans are really annoyed that Alexander/Deanna, Lwaxana/Worf and Geordi/Selar are up and about, so they order them back to their cells. Worf (as Lwaxana) isn’t having any of that though and, in a single, beautiful moment I *really, really* wish Majel Barrett had gotten to act out, throws his/her head back, yells out a battle cry, body slams the Ergeans and powerbombs all three of them to the mat while bellowing “Cowards! This time you have bitten off a great deal more than you can chew!”.

So the Ergeans are really annoyed that Alexander/Deanna, Lwaxana/Worf and Geordi/Selar are up and about, so they order them back to their cells. Worf (as Lwaxana) isn’t having any of that though and, in a single, beautiful moment I *really, really* wish Majel Barrett had gotten to act out, throws his/her head back, yells out a battle cry, body slams the Ergeans and powerbombs all three of them to the mat while bellowing “Cowards! This time you have bitten off a great deal more than you can chew!”.

Frankly if you’re not already sold on this book by the concept of Majel Barrett powerbombing aliens and immediately convinced this series is one of the greatest things in the history of Star Trek, there’s nothing more I can do for you, so you might as well pack it all in now.

Back on the Enterprise, the Sakerions exposit that while outsiders have long believed that the Ergeans were governed by a succession of triumvirates, this is actually not the case. In truth, there was only ever one triumvirate, but they gave themselves functional immortality through a machine that allowed consciousnesses to be transplanted from one body to the next. And due to the Ergeans’ strong regard for life, the donor body’s original consciousness was transplanted as well, so nobody would ever have to die. But over time, the triumvirate grew authoritarian as Ergean society went through hardship, and one day the people refused to transplant their consciousnesses, instead sealing them away in mind receptacles until the time where it was felt they would be needed again. The Sakerions think the Ergeans might feel that time has come, and they’ve chosen the bodies of Worf, Selar and Deanna as the latest “volunteers”. Captain Picard asks if the process is reversable, and the Sakerions say yes (luckily for us they managed to…acquire…the necessary technology from the Ergeans) but they will have to hurry, as the bonds between consciousnesses and their original bodies break down if they are separated for too long.

Down on the planet, the issue’s requisite fight scene is still going on. Selar (as Geordi) is busting some sick action moves until one of the Ergeans grabs Deanna who, as Alexander, is not in much of a position to fight back. It looks like Selar will be forced to surrender too until Worf (again as Lwaxana) unloads a phaser rifle round into his chest from across the room. Lwaxana herself re-enters the picture shortly thereafter, and is decidedly not amused by the alleged indignity of being forced to become a warrior. This is no throwaway joke either, because it’s promptly followed by a truly great scene where Alexander returns to the surface and expresses shock and horror at being able to feel the emotions of his attackers the same way Deanna Troi can, because it makes it difficult to be a warrior. To which Selar responds, “this is why Vulcans prefer peace”.

Geordi comes back and explains that he’s found a way out in the form of a sealed off room with a large energy flow.…

Continue Reading

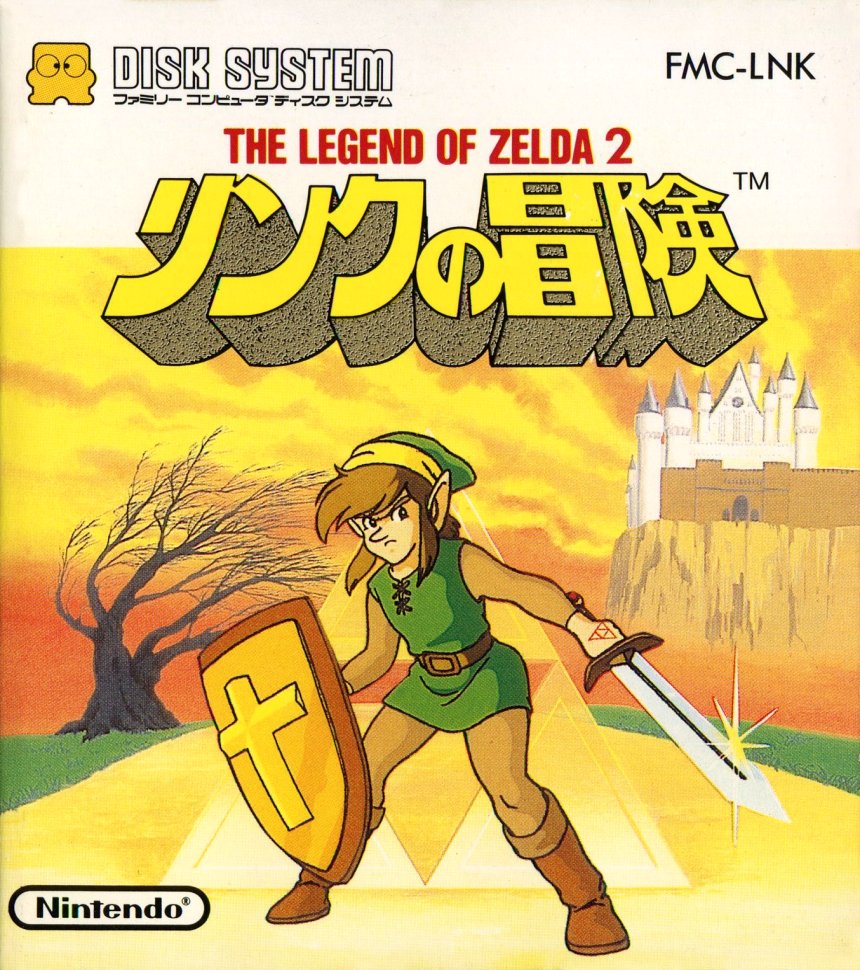

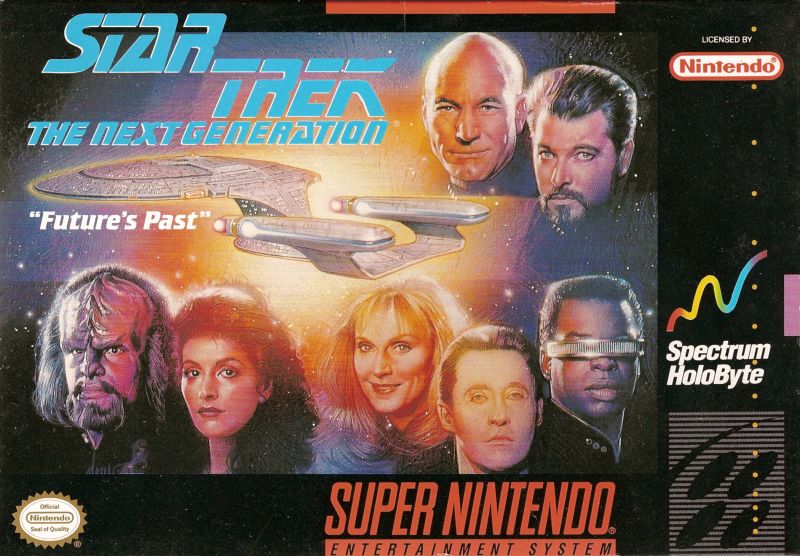

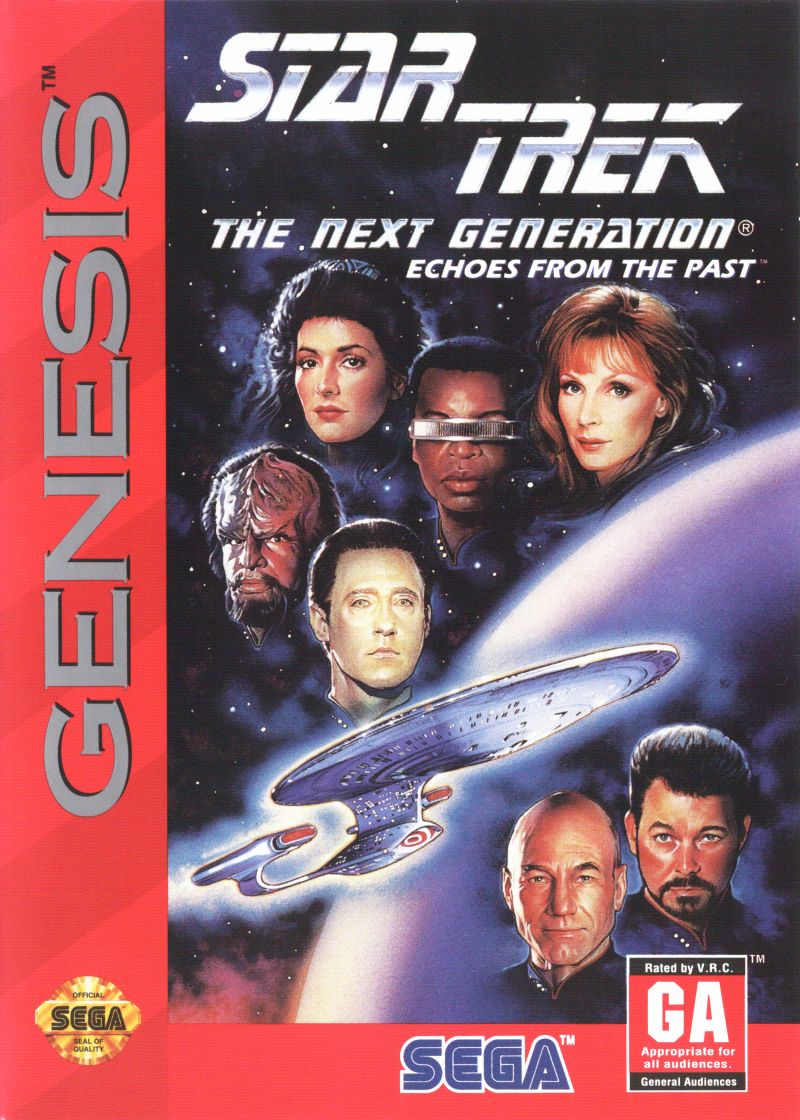

Video game sequels are a different beast than sequels in other mediums. In video games, a sequel is typically expected to improve upon its predecessor because video games are intensely technical. Since a game is thought of at least partly as a feat of software engineering, sequels are approached as a honing, refining and improvement of the original as much as they are a thematic and aesthetic continuation of them. In other words, we should think of video game sequels as new and improved models as much as the next chapter of a story, if not more so. On the other hand, the nature of a sequel demands in any medium of genre demands narrative escalation.

Video game sequels are a different beast than sequels in other mediums. In video games, a sequel is typically expected to improve upon its predecessor because video games are intensely technical. Since a game is thought of at least partly as a feat of software engineering, sequels are approached as a honing, refining and improvement of the original as much as they are a thematic and aesthetic continuation of them. In other words, we should think of video game sequels as new and improved models as much as the next chapter of a story, if not more so. On the other hand, the nature of a sequel demands in any medium of genre demands narrative escalation.

So the Ergeans are really annoyed that Alexander/Deanna, Lwaxana/Worf and Geordi/Selar are up and about, so they order them back to their cells. Worf (as Lwaxana) isn’t having any of that though and, in a single, beautiful moment I *really, really* wish Majel Barrett had gotten to act out, throws his/her head back, yells out a battle cry, body slams the Ergeans and powerbombs all three of them to the mat while bellowing “Cowards! This time you have bitten off a great deal more than you can chew!”.

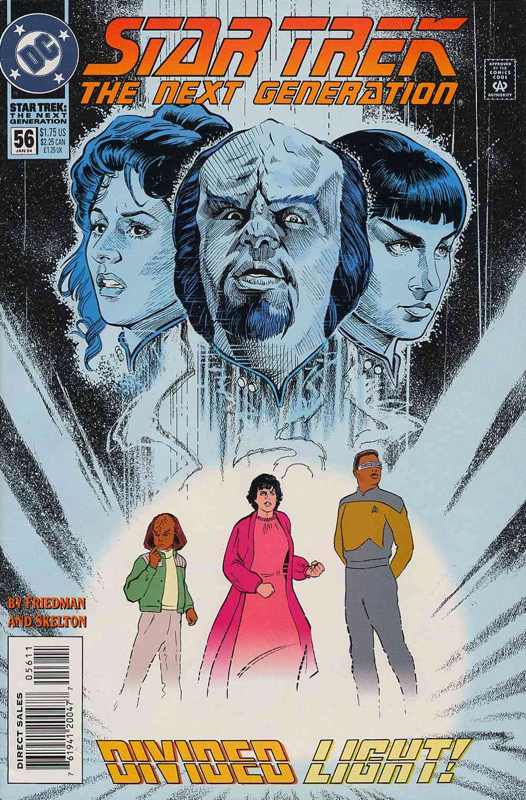

So the Ergeans are really annoyed that Alexander/Deanna, Lwaxana/Worf and Geordi/Selar are up and about, so they order them back to their cells. Worf (as Lwaxana) isn’t having any of that though and, in a single, beautiful moment I *really, really* wish Majel Barrett had gotten to act out, throws his/her head back, yells out a battle cry, body slams the Ergeans and powerbombs all three of them to the mat while bellowing “Cowards! This time you have bitten off a great deal more than you can chew!”. This is far and away among the weirder story arcs in the DC Star Trek: The Next Generation series. And given this is a comic book line that had the Enterprise literally meet Santa Claus in 1987, that goes a way towards saying something. And yet Divided Light is *just* audacious and weird enough to work: Michael Jan Friedman’s signature deft hand at writing the crew and his knack for having his stories’ main themes and motifs reoccur on multiple levels makes this one memorable for all the right reasons instead of all the wrong ones. Perhaps most importantly for our purposes, it marks the beginning of a critical and formative time when the spin-off media, particularly the comic books, steered the course of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

This is far and away among the weirder story arcs in the DC Star Trek: The Next Generation series. And given this is a comic book line that had the Enterprise literally meet Santa Claus in 1987, that goes a way towards saying something. And yet Divided Light is *just* audacious and weird enough to work: Michael Jan Friedman’s signature deft hand at writing the crew and his knack for having his stories’ main themes and motifs reoccur on multiple levels makes this one memorable for all the right reasons instead of all the wrong ones. Perhaps most importantly for our purposes, it marks the beginning of a critical and formative time when the spin-off media, particularly the comic books, steered the course of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

When I was writing my first volume of Vaka Rangi, I was faced with a dilemma on how to frame the book. I have little to no personal or nostalgic connection to the original Star Trek or its animated sequel so my episode-to-episode reactions were by definition going to be mostly as I saw it. But I still wanted to come up with something unique to say about this most important period of Star Trek history, so I initially decided to structure the book around telling as “real” a story about the franchise’s formative years as I could, with a careful eye towards historical mythbusting in general, in particular how it pertained to the shows creator, the ever-mythologized Gene Roddenberry. I soon realised, however, that this was a task far too massive for me to undertake given the scope of the project I had cast, and quickly found myself intimidated and overwhelmed by the sheer scale of conflicting stories and seemingly deliberate disinformation surrounding Roddenberry and Star Trek. While I still hoped to convey a general idea for what Star Trek actually was and was envisioned as being (and I do feel, and hope, I managed some degree of success), the behind-the-scenes stuff became far too complicated a topic for me to tackle with any aspirations of genuine comprehension.

When I was writing my first volume of Vaka Rangi, I was faced with a dilemma on how to frame the book. I have little to no personal or nostalgic connection to the original Star Trek or its animated sequel so my episode-to-episode reactions were by definition going to be mostly as I saw it. But I still wanted to come up with something unique to say about this most important period of Star Trek history, so I initially decided to structure the book around telling as “real” a story about the franchise’s formative years as I could, with a careful eye towards historical mythbusting in general, in particular how it pertained to the shows creator, the ever-mythologized Gene Roddenberry. I soon realised, however, that this was a task far too massive for me to undertake given the scope of the project I had cast, and quickly found myself intimidated and overwhelmed by the sheer scale of conflicting stories and seemingly deliberate disinformation surrounding Roddenberry and Star Trek. While I still hoped to convey a general idea for what Star Trek actually was and was envisioned as being (and I do feel, and hope, I managed some degree of success), the behind-the-scenes stuff became far too complicated a topic for me to tackle with any aspirations of genuine comprehension.