Totemic Artefacts: Playmates Star Trek: The Next Generation Waves 3 and 4

Last week we talked about the expression of the Beautiful throughout the history of Doctor Who, and gleaned different kinds of aesthetics employed by the show in the process – from awe at new, strange places… to the banal objectification of women… to an almost ritualized praise of monsters in the modern era. And it’s this latter sense of beauty that I find most interesting, given how monsters are now used in Doctor Who, especially in the Moffat era. Because monsters are no longer just villainous plot devices for generating scares. Quite often they are secret protagonists, and weighted with symbolic value, especially when juxtaposed with our main characters such that they become telling metaphors. This latter process I call the “monstering” of a character, and of particular interest to me is how Amy Pond becomes consistently monstered during her time on the show.

Last week we talked about the expression of the Beautiful throughout the history of Doctor Who, and gleaned different kinds of aesthetics employed by the show in the process – from awe at new, strange places… to the banal objectification of women… to an almost ritualized praise of monsters in the modern era. And it’s this latter sense of beauty that I find most interesting, given how monsters are now used in Doctor Who, especially in the Moffat era. Because monsters are no longer just villainous plot devices for generating scares. Quite often they are secret protagonists, and weighted with symbolic value, especially when juxtaposed with our main characters such that they become telling metaphors. This latter process I call the “monstering” of a character, and of particular interest to me is how Amy Pond becomes consistently monstered during her time on the show.

But what does it mean “to be monstered?” What does that look like? And how unique is it to the modern era? To answer those questions, I’ll step briefly back into the past, to The Android Invasion, aa 4th Doctor story with Sarah Jane in Season 13. In The Android Invasion the Doctor and Sarah Jane have landed on an alien planet that looks like Earth, but it isn’t Earth, it’s the staging ground for an alien invasion that will use android duplicates of certain Earthlings, which is pretty standard Doctor Who fare when you think of it. Anyways, there’s this great cliffhanger where Sarah Jane has been replaced by an android duplicate, only the Doctor has figured it out and attacks her, wrestling her to the ground. Her face falls off, revealing so much circuitry.

Yes, this the best moment in the otherwise fairly dreadful tale (it was written by Terry Nation, for gods’ sakes), but it’s also freighted with some potentially interesting literary readings. First of all, Sarah Jane isn’t the only android duplicate – there’s some regular UNIT personnel, and even the Doctor, all monstered by androids. It’s uncanny because we see characters we’ve known as “good” behaving in ways that are “not good,” which is rather transgressive. Aside from that, though, there’s the opportunity for the nature of the particular monster to inform us about our characters’ natures. This works particularly well in the monstering of Benton and Harry – they’re programmatic characters. Sadly, Terry Nation is not a particularly writerly writer, as the monstering of both the Doctor and Sarah Jane really don’t say much about them at all – well, unless we stretch it a bit. For example, Sarah Jane’s role as a Companion is often programmatic, from assisting in asking questions for the audience to serving as a plot device. And even the Doctor, well, it’s a role that could be (and has been) played by all kinds of performers, such that he doesn’t even have a real face anymore.

Contrast this with the monstering of Amy in Night Terrors. In Night Terrors, we see Amy transformed into a deadly Wooden Doll, the product of a child’s nightmare, a child who’s afraid of being abandoned. …

Contrast this with the monstering of Amy in Night Terrors. In Night Terrors, we see Amy transformed into a deadly Wooden Doll, the product of a child’s nightmare, a child who’s afraid of being abandoned. …

Let’s start with the good, a phrase that pretty decisively tips my hand as to the overall shape of this review. The direction is largely solid – Sapochnik’s sense of composition is reliably impeccable. The wide shot of Davos after he’s discovered what happened to Shireen is probably the most straightforward of them, but it’s hardly the only one. His shots emphasizing the absolute carnage are things we haven’t seen the show do with violence before. The long take of Jon in combat is exquisite, as is the scene of Jon crawling his way out of the crush.

Many of the small moments are similarly strong. Sansa riding away from the parlay is delicious, a beautiful setup for the final scene, Sophie Turner getting to play imperious badass and absolutely nailing it. Her smile as Ramsay is ripped apart is perfectly poised, at once capping off a long-awaited bit of narrative payoff and letting it go just a little too far. Davos and Tormund’s version of “the men chatting before the battle” is delightful. And pretty much everything in Meereen is fantastic, from Peter Dinklage’s understatement to the basic satisfaction (and intelligence) of opening an episode that had been promoted as if it was another “Blackwater” or “The Watchers on the Wall”-style single location battle with a scene in Meereen, and more to the point with a spectacle-laden battle scene in Meereen. And then of course there’s “I never demand, but I’m up for anything really,” which is straightforwardly the best line of the episode, and probably of the season.

The problems, then. Sapochnik’s direction is mostly excellent, but his taste for visual perversity, so effective in “Hardhome” when he was doing zombie horror battles, is just irritating here. Things like the gratuitous shot of Rickon’s body being riddled with additional arrows, or the decision to play Wun Wun’s death as a punchline with an arrow going through his eye are just crass – the worst instincts of the Red Wedding distilled into singular shots, included for no other reason than the fact that Game of Thrones is a show that is apparently fundamentally obliged to include tawdry spectacle.

Furthermore, while sloppy plotting vulnerable to refrigerator logic is a standard feature of Game of Thrones that I’m usually not bothered by, this episode is particularly egregious. Many of these are small things that can easily be ignored – the degree to which the starving dogs comply with dramatic pacing in exactly when they devour Ramsay, the fact that Sansa wasn’t actually there when Ramsay said he hadn’t fed them, or Ramsay’s mysteriously improving aim as Rickon recedes. Their aggregate is perhaps a particularly bad run of sloppiness, but none of it is outside the realm of what the show’s basic narrative engine depends on the viewer being willing to forgive.

But the Rickon scene also starts to get at some of the larger problems. Ramsay’s supernatural archery skills are highlighted by the fact that the scene is a drawn out spectacle of unpleasant anticipation.…

|

| Burn Goreman finally lands a job more ridiculous than Torchwood. |

Review of “Battle of the Bastards” will be along later today – I’ve got an early morning, so can’t get it up the night before I fear.

State of Play

The choir goes off. The board is laid out thusly:

Lions of King’s Landing: Tyrion Lannister, Jaime Lannister, Cersei Lannister

Dragons of Meereen: Daenerys Targaryen

Direwolves of the Wall: Jon Snow, Bran Stark

The Mockingbird, Petyr Baelish

Roses of King’s Landing: Margaery Tyrell

Archers of the Wall: Samwell Tarly

The Direwolf, Sansa Stark

Shields of King’s Landing: Brienne of Tarth

Chains of King’s Landing: Bronn

With the Bear of Meereen, Jorah Mormont

The episode is in seven parts. The first runs eight minutes and is set in Meereen. The opening image is of the fire by which Grey Worm and Missandei are sitting.

The second runs five minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by hard cut, from Daenerys overlooking her city as the hundred-and-sixty-three people she crucified scream in agony to Jaime and Bronn swordfighting.

The third runs three minutes and is set on a boat. The transition is by dialogue, from Tyrion and Jaime talking about Sansa to Sansa.

The fourth runs two minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by dialogue, with Littlefinger talking about his new friends and saying the Tyrell words to Margaery and Olenna.

The fifth runs four minutes and is set at the Wall. The transition is by hard cut, from Margaery’s stunned face to Jon and the men sparring in the yard of Castle Black.

The sixth runs ten minutes and is in three sections; it is set in King’s Landing. The first section is two minutes long; he transition is by hard cut, from Locke and Jon to Cersei drinking. The second section is four minutes long; the transition is by family, from Cersei and Jaime Lannister to Tommen Baratheon, and by dialogue, with Cersei and Jaime discussing the security around Tommen’s bedroom to Margaery breaching it. The third section is five minutes long; the transition is by family, from Tommen to Jaime.

The seventh part runs nineteen minutes and is in four sections; it is set at and around the Wall. The first section is five minutes long; the transition is by hard cut, from Brienne and Pod riding away to Sam fussing at scrolls. The second section is six minutes long; the transition is by dialogue, from Jon Snow talking about a mission to Craster’s to Karl Tanner of Gin Alley drinking wine from the skull of Jeor fucking Mormont. The third section runs five minutes long; the transition is by family, from Ghost to Summer. The fourth section is two minutes minutes long; the transition is by image, from Craster’s Keep to Craster’s last son. The final image is of a baby landing on a snake and acquiring purple eyes.

Analysis

On its most elemental level, a further development of the tendency towards compacted play – a mere seven parts, without even the reliance on a big set piece.

I’ve successfully moved, and even unpacked most of the boxes. So that’s nice. Settling and finally getting back to work, at least when I can avoid being horribly distracted by the book I’m reading. (It’s a really good book, but alas I can’t mention the title.) Finally back to work on Last War in Albion, both revisions and new material. Just had cause to crack open How To Draw Comics the Marvel Way. And the Neoreaction a Basilisk copyedits are almost done. So life is largely good.

“Battle of the Bastards” review will probably be up Monday morning, as Jill’s first day of work is Monday and I’m somewhat disinclined to stay up til 2-3am reviewing Game of Thrones the night before that.

In other news, friend of the blog James Wylder is running a Kickstarter for Goblinpunk, a Pathfinder and D&D compatible adventure. They’re just under $270 from goal with just over a day remaining, so if that’s a thing that interests you, well, do the obvious thing.

And that’ll do for this week, I reckon.…

First, the Orlando shooting massacre happened. Then we had some issues with an Oi! Spaceman recording. Then some personal issues kept us away from the microphones for a few days. Long story short, I don’t have a lot of new content for you this week. The only new episode anywhere in the Oi! Spaceman family was this intermission episode I did by myself over on They Must Be Destroyed on Sight, discussing three of the Westerns that James and Kevin have chatted about in their last two episodes, all of which I’d seen for the first time: The Hanging Tree, My Darling Clementine, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence.

First, the Orlando shooting massacre happened. Then we had some issues with an Oi! Spaceman recording. Then some personal issues kept us away from the microphones for a few days. Long story short, I don’t have a lot of new content for you this week. The only new episode anywhere in the Oi! Spaceman family was this intermission episode I did by myself over on They Must Be Destroyed on Sight, discussing three of the Westerns that James and Kevin have chatted about in their last two episodes, all of which I’d seen for the first time: The Hanging Tree, My Darling Clementine, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence.

The Western genre is very much about the limnal space between the ideals of “civilization,” (as problemmatic as the term can be in any context) and those of “open range.” Namely: how do we as a society deal with bad actors in our midst, with violence committed by those in our communities. Should we respond to violence with more violence, or are there other (more “civilized”) ways of responding? These ideas were very much on my mind when I recorded the episode, as I recorded it the evening after the murder of fifty queer people during Pride week, and I definitely referenced the news when discussing the films. It’s a quiet episode; I was emotionally raw (partly from arguing with alt-right kiddy-Nazis on Twitter) and more than a little numb. Go give it a listen; I’m sure some of the questions of masculinity and femininity in classic Westerns will come up again in a future essay I write in this space.

Given that Oi! Spaceman is new to this site, I thought I’d take the opportunity of a light programming week to show off a few episodes I’m particularly proud of. Phil has basically brought us on to talk about sex and gender, so I should probably point out our most sex-heavy episodes. The first is our Series 8 recap, called “An Abusive Polyamorous Triad,” in which we examine the Doctor/Clara/Danny dynamic through the lens of polyamory. (That’s also the episode where we officially “came out” and so we talk a bit about polyamory in general there for the curious.) More recently, we discussed the 2015 Christmas Special in “Genocide and Polyamory,” which is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. That’s the one where I briefly discuss my vision of the sexual prowess of the various New Who Doctors, by the way, while Shana very audibly rolls her eyes.

Away from the sexy talk, I’m quite proud of our Daleks’ Master Plan discussion, which I called “Missing Episodes and Moral Culpability,” and borrows heavily from Phil’s old Tardis Eruditorum entry on DMP. Our chat about The Ribos Operation, “One Day, Even Here…” is also one I like a lot, and since that one both references criticisms Jack made of our discussion of The Invasion of Time and references his excellent piece on The Ribos Operation quite heavily, fans of Jack may want to give that one a whirl. …

“’Suppose that truth is a woman-And why not? Aren’t there reasons for suspecting that all philosophers, to the extent that they have been dogmatists, have not really understood women?’ There is thus a residue that philosophy has not known how to read, for which it has not been able to account. When matters become urgent or when truth is at stake, Nietzsche gives this residue a name: woman.”

–Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche, as translated by Judith Norman, as cited by Avital Ronell in conversation with Anne Dufourmantelle in Fighting Theory

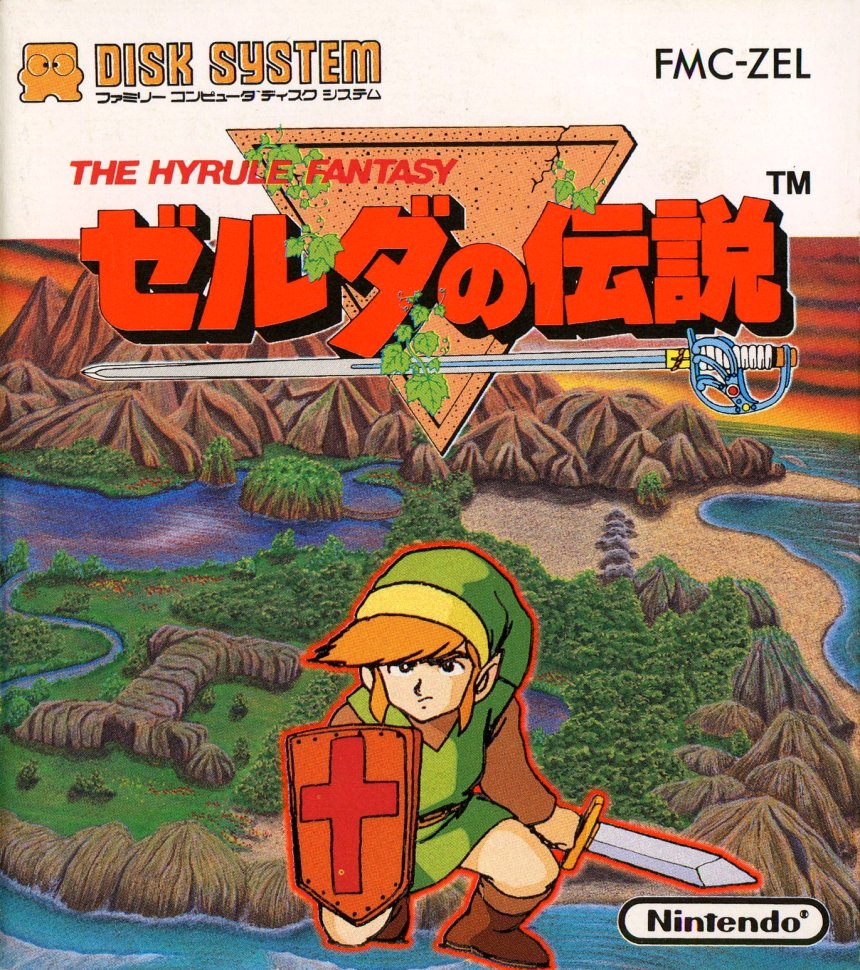

Zelda no Densetsu (lit. The Legend of Zelda) opens up with the declaration that this is a legend that has been “passed down from generation to generation”.

The Legend of Zelda has thus been, from the very beginning, something from the recesses of our shared memory. The secret history of Zelda is that she truthfully only exists at her purest in an unknowable primordial state lost long ago to the collective dreamtime. Even the “original” Legend of Zelda arrived in its present state shaped by the expectations and experiences of its previous incarnations. It is also, first and foremost, a fairy tale in the most classical sense: It is a coming of age story about a boy becoming a hero and, through doing so, finding his true self.

Not only is The Legend of Zelda a fairy tale, it’s a very specific and particular fairy tale, namely, Super Mario Bros. Designers Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka were working on Zelda no Densetsu for the Famicom Disk System at the exact same time they were working on Super Mario Bros. for the Famicom (though Super Mario Bros. was to be released first in 1985, a year ahead of Zelda in 1986), and the two titles wound up sharing a great deal of thematic concepts and overtones. One of which is the plot: In both games, a peaceful fantasy kingdom is invaded by an evil wizard from another land. The only person powerful enough to stop the wizard is the kingdom’s princess regent, who is captured and locked away so she can’t fight back. A humble, unassuming everyman steps forth and volunteers to go on a journey to free the princess, repel the invaders and bring peace back to the land.

The first way in which The Legend of Zelda is transformed from its dream-state thus comes about as consequence of being filtered through the lens of Super Mario Bros. And there are certain things irrevocably lost and altered in translation: Most notably, Super Mario Bros., as we have since learned from games like Super Mario Bros. 3 and recent statements from Mr. Miyamoto, is fundamentally a travelling stage show reinterpreted as a video game. There is no constructed “Mario Universe” and the Mario characters are merely a troupe of actors. The basic story of Super Mario Bros. is reiterated in every “serious” mainline Mario game because it is nothing more than a stage show being performed in different venues at different times with different interpretations from the company.…

From worst to best of what I read, with books that I wasn’t willing to pay money for.

Lazarus #22

I may be putting this at the bottom for my own failings as opposed to the book’s, given that I discovered an entire plotline I’d apparently completely failed to understand in the recap pages. (I’d been parsing the scenes of the second Forever as flashbacks for some reason.) Anyway, this is a fine issue of Lazarus, but I have to admit, there’s not a lot that’s fresh in this book at this point, and not only on the level of “what happens all feels pretty standard and expected,” but on the level of “it is difficult to even imagine how the book could surprise me.” Which I suppose is an odd question to ask, as it wouldn’t be a surprise, but all the same, this just isn’t a book I’ve got much excitement for right now and is becoming a bit of a loyalty read.

Spider-Gwen #9

I have a much easier time with Spider-Gwen when she’s in conversation with the rest of the Marvel Universe, as opposed to when she’s doing stories in her own bubble, and started this book mildly annoyed and a bit underwhelmed by it and wondering if I was going to keep going. I ended the book much more enthused and interested, after some good character notes. There’s a mild impatience for the silly and obviously temporary “Gwen only has a finite number of doses of power left” status quo to go away so that the book can get back to its actual premise – it’s exactly the sort of plot superhero comics are slightly crap at. But for the most part, fun superheroics.

Mercury Heat #10

Missed that this came out and just snagged it. A very “gets the job done” sort of issue, the job being a pseudo-conclusion that gives way to a nice big cliffhanger that will presumably close out this arc. There’s not a lot new to introduce, though, and most of the intriguing questions left by previous issues have resolved into answers that, while perfectly fine and good storytelling, are, as is often the case, somewhat less interesting than the open-ended questions. So nothing wrong with it, but not an exceptionally gripping issue either.

Klaus #6

The Morrisonia really hits in full, with the sort of symbolism-infused vision quest you expect from Morrison. On the one hand this is a bit sad, the book seeming to give up most of what made it feel fresh and innovative in favor of predictability. On the other hand, this book has been wheel-spinning, and even if Morrison is leaning hard on old favorites here, it’s still providing the book with a new momentum that it hasn’t really had since issue #2 or so, making me at least a bit interested in the conclusion, even as it’s pretty clear how everything is going to shake out. This remains Morrison’s best work in a couple years, for better and for worse.…

I’ve been thinking about doing another essay on monstering in Doctor Who, especially with regards to Amy Pond, but it occurs to me that this would really benefit in hindsight of a full survey on the show’s conception of beauty. Which is to say, I think the process of “monstering” is part and parcel of the modern show’s aesthetics, and what better way to explore those aesthetics than to come to some sort of understanding of the place where the Beautiful stands within it? Well, there’s probably several other better ways, but when it comes to Amy Pond, I think “beauty” isn’t a bad place to start. Not because Karen Gillan is classically beautiful, but because the character she plays actually articulates a philosophy of beauty that I find altogether more interesting:

I’ve been thinking about doing another essay on monstering in Doctor Who, especially with regards to Amy Pond, but it occurs to me that this would really benefit in hindsight of a full survey on the show’s conception of beauty. Which is to say, I think the process of “monstering” is part and parcel of the modern show’s aesthetics, and what better way to explore those aesthetics than to come to some sort of understanding of the place where the Beautiful stands within it? Well, there’s probably several other better ways, but when it comes to Amy Pond, I think “beauty” isn’t a bad place to start. Not because Karen Gillan is classically beautiful, but because the character she plays actually articulates a philosophy of beauty that I find altogether more interesting:

WARRIOR AMY: All those boys chasing me, but it was only ever Rory. Why was that?

AMY: You know when sometimes you meet someone so beautiful, and then you actually talk to them, and five minutes later they’re as dull as a brick? Then there’s other people, and you meet them and think, “Not bad, they’re okay.” And then you get to know them, and their face just sort of becomes them, like their personality’s written all over it. And they just turn into something so beautiful.

BOTH: Rory’s the most beautiful man I’ve ever met.

Which kind of gets where I’m going with this idea, namely that we have multiple conceptions of beauty, which we can roughly bifurcate into those predicated on appearances, and those predicated on interiority. This is actually a false dichotomy, which we’ll get to later on, but for now this represents the axis I want to explore, especially when we get to the Revival. Anyways, what I’ve done is look for instances of the word “beautiful” and its variants within the show’s dialogue. This was done using a blanket google site search on Chrissie’s Doctor Who transcripts at chakoteya.com, coupled with individual searches of all the remaining Revival episodes, plus City of Death, for as it turns out google site search isn’t as thorough as I’d hoped. As such, I’ve haven’t thoroughly surveyed all the Classic stories, so if you remember any pertinent lines from something not covered here, please say so in the comments.

Now obviously this isn’t going to fully capture what the show actually finds beautiful. Dialogue, after all, is more reflective of the characters speaking it, and as such certainly can’t represent the implied authors of Doctor Who. Still, for a character to conceive of something as being beautiful, the implied authors have to conceive of it too, even if they might disagree. Which is to say, there’s still an acknowledgment of a kind of beauty that someone can behold. Furthermore, it’s much more difficult to pin down an acknowledgement of “beauty” without being explicitly told. Not impossible, no – for example, the production cues of Doomsday, when Rose is finally torn from the Doctor through their last moments on the beach, clearly flag an understanding of tragic beauty, whether it’s from the score or the location design or just from the story itself. …